Overview

Welcome to Country

Foreword

Introduction

Preface

Essays

Stacie Piper, Curator

As a Wurundjeri, Dja Dja Wurrung and Ngurai Illum Wurrung curator, I see my key role as being a storyteller and a story facilitator, connecting past and present, and allowing the continuity between them to show through. This is the story of how WILAM BIIK came to be.

When I was appointed by TarraWarra Museum of Art as the First Nations Curator for the second iteration of Yalingwa back in May 2019, I knew the next two years were going to be a journey of growth and challenges. I was already in a role at Bunjilaka at Melbourne Museum in which I facilitated projects that amplified the voices of Victorian First Peoples and so, given Yalingwa is an initiative which seeks to support and promote contemporary Indigenous art and curatorial practice from the South East regions of Australia, I knew this would be a major platform from which to expand on this experience.

I also understood that this position brought with it a huge responsibility and, with this in mind — before the COVID–19 outbreak, before lockdowns, and before our lives underwent immense change — I was fortunate to embark on a series of professional development opportunities. For the first time I attended the Cultural Keepers: Darwin Aboriginal Art Fair Foundation Indigenous Curators Program and Symposium, where I worked with two Art Centres based in remote regions of Arnhem Land — it was an experience I will never forget! I then went on to attend a number of significant exhibitions including: River on the Brink: Inside the Murray- Darling Basin at S.H. Ervin Gallery in Sydney which included the powerful works of Barkandji Elder Uncle Badger Bates; TARNANTHI Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art at the Art Gallery of South Australia directed by Nici Cumpston, where I was in the company of some of the Country’s most accomplished arts practitioners (I was like a tiny fish in a big ocean, or should I say a baby eel in a giant river!); and I also visited many incredible exhibitions in my home of Narrm. I finished off the year of 2019 by attending the National Gallery of Australia’s Indigenous Arts Leadership and Fellowship program where I was one of ten Indigenous arts professionals selected to undertake this intensive course in its 10th year — I am now one of 100 Alumni of First Nations blak1 excellence!

However, while I was having the experience of a lifetime, it was also an immensely challenging time as I started to see the common themes of environmental degradation, destruction of habitat, and the desecration of Country being shared by artists and communities everywhere I travelled. From the high rates of land clearing to the ongoing devastation of the vital waterways of the Murray-Darling Basin resulting in mass fish kills, I discovered that I was not alone in feeling that we are losing our beautiful Country to logging, mining, drilling, over extraction of our rivers, soil quality decline, and natural disasters bought about by climate change. And then came the catastrophic bushfires which engulfed enormous swathes of habitat and devastated innumerable populations of native flora and fauna during the summer of 2019–20. I myself have been in the midst of a three-year long campaign against clear fell logging of the Central Highlands of Victoria, home to many endangered species, and I could sense the desperation and the urgency of needing to protect Country.

What I came to realise while travelling across the Country, was that despite these environmental crises we face, our mobs still have this beautiful light spirit, as shown in the title of the first Yalingwa exhibition curated by Hannah Presley, A Lightness of Spirit is the Measure of Happiness. Often when sharing culture as storytellers, we don’t focus solely on the problems we face (we save that for the rallies we hold throughout the year), but rather on our enduring cultural practices that we have been enacting for thousands of generations to sustainably care for Country.

So, when it came to curating this exhibition I decided there was only one place to start — with Country, the story of Home. I have always been taught by my Grandmother, Mother, Aunties, Uncles, that for everything in life there are protocols which we have followed for thousands of generations, cultural values and law (lore) which have governed our communities and enabled us to live safely within a structure which informs marriage and kinship, trade, how we travel Country to access resources, how we conduct business, and how to be custodians of the lands and waters to which we belong. So I started there.

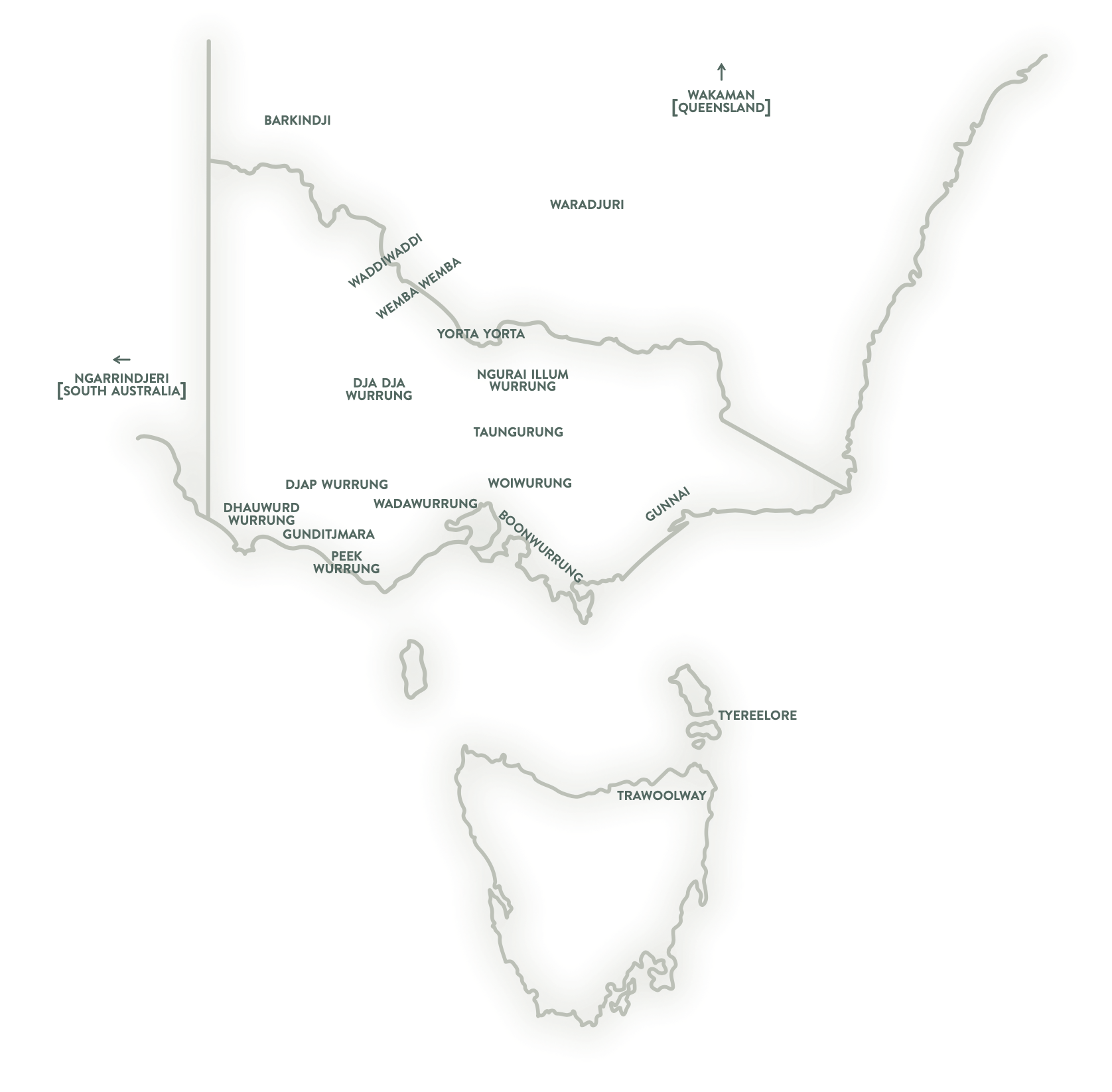

To seek out artists for this vision, I began by mapping out the connections of traditional songlines, waterlines and bushlines. The bushlines are how I describe what First Peoples see when observing Country across the mountains of the Alpine forest regions of Victoria. For example, the Wurundjeri, Taungurung and the Gunnai/Kurnai people of South East Australia, all share sacred Bush Country (forests, as Western knowledge systems would describe). This mountainous terrain is home to some of the tallest flowering gum trees in the world; the Mountain Ash (Eucalyptus regnans). These Mountain Ash store some of the highest levels of carbon on the planet, and for hectares of this precious ecosystem to be continually logged on a daily basis, is devastating not just for First Peoples, but also for local communities who revere and respect these ancient and majestic trees. The post-logging industrial scale burns cause even further destruction by triggering soil loss and the leaching of nutrients which has detrimental impacts on biodiversity and nearby waterways, and this damage is abhorrent during a climate emergency. On this part of Country we also see some of the oldest geological formations in the enormous granite boulders and large rocky outcrops. Sculpted by erosion and natural forces over eons, they carry stories of deep time and Creation.

The waterlines I refer to connect the language groups who occupy the freshwater and the saltwater regions: the Barkindji, the people of the Barka (Darling River); the Dhungala (Murray River) connecting the Ngurai Illum Wurrung, Yorta Yorta, Wemba Wemba, Waddi Waddi, and Ngarrindjeri; the Wiradjuri who have a deep connection to the Murrumbidjeri (Murrumbidgee River) which, from its source high in the Australian Alps, flows for hundreds of kilometres West to its confluence with the Dhungala. The upper reaches of the Goulburn River and its tributaries north of the Great Dividing Range, also part of the Murray-Darling basin, flow through the lands of the Taungurung people. To their West the Dja Dja Wurrung are the people of the region surrounding the Upper Loddon and Avoca rivers while to the South is the Birrarung (Yarra River), which flows from Mt Baw Baw to Port Philip Bay and is central to the cultural life and identity of the Wurundjeri people.

These lifelines have sustained First Peoples of South East Australia for millennia, however, within only 250 years of colonisation we have witnessed the devastating impacts that irrigation and the redirecting of water have had on these waterlines and our Communities.

I then traced the course of the rivers down to Bunurong/Boonwurrung Country where the freshwater rivers meet the sea. The people of these lands are connected to the Birrarung through Port Phillip Bay, I then followed the water over the ocean across Bass Strait to the Tyereelore and Trawoolway people of Tasmania. From here I mapped a path back up and West through Wadawurrung Country, following the Werribee River and then along the Great Ocean Road to Aireys Inlet. Further to the South West coastal region we find the volcanic plains of the Gunditjmara, home of the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, which contains one of the world’s most extensive and oldest aquaculture systems which were constructed from the abundant local volcanic rock. Heading North again to return to the lower Murray we traverse Djap Wurrung Country and encounter the mountainous region of Gariwerd (The Grampians), home to the largest number of significant and ancient Aboriginal rock art paintings and shelters in southern Australia.

The songlines contain everything I have described within my personal understanding and explanation of ‘bushlines’ and ‘waterlines’, except they also hold a greater, intangible energy — our Creation stories of Bunjil singing into being Country, the land, the water, the animals, and finally, the people. Songlines are our footprints, our kinship, our connections, our songs and dances, and are a living repository of knowledge for how to care for Country, giving us our voices to continue to sing Country in our travels.

It was this process of observing and mapping lines and being guided by protocols which directly informed my curation of WILAM BIIK.

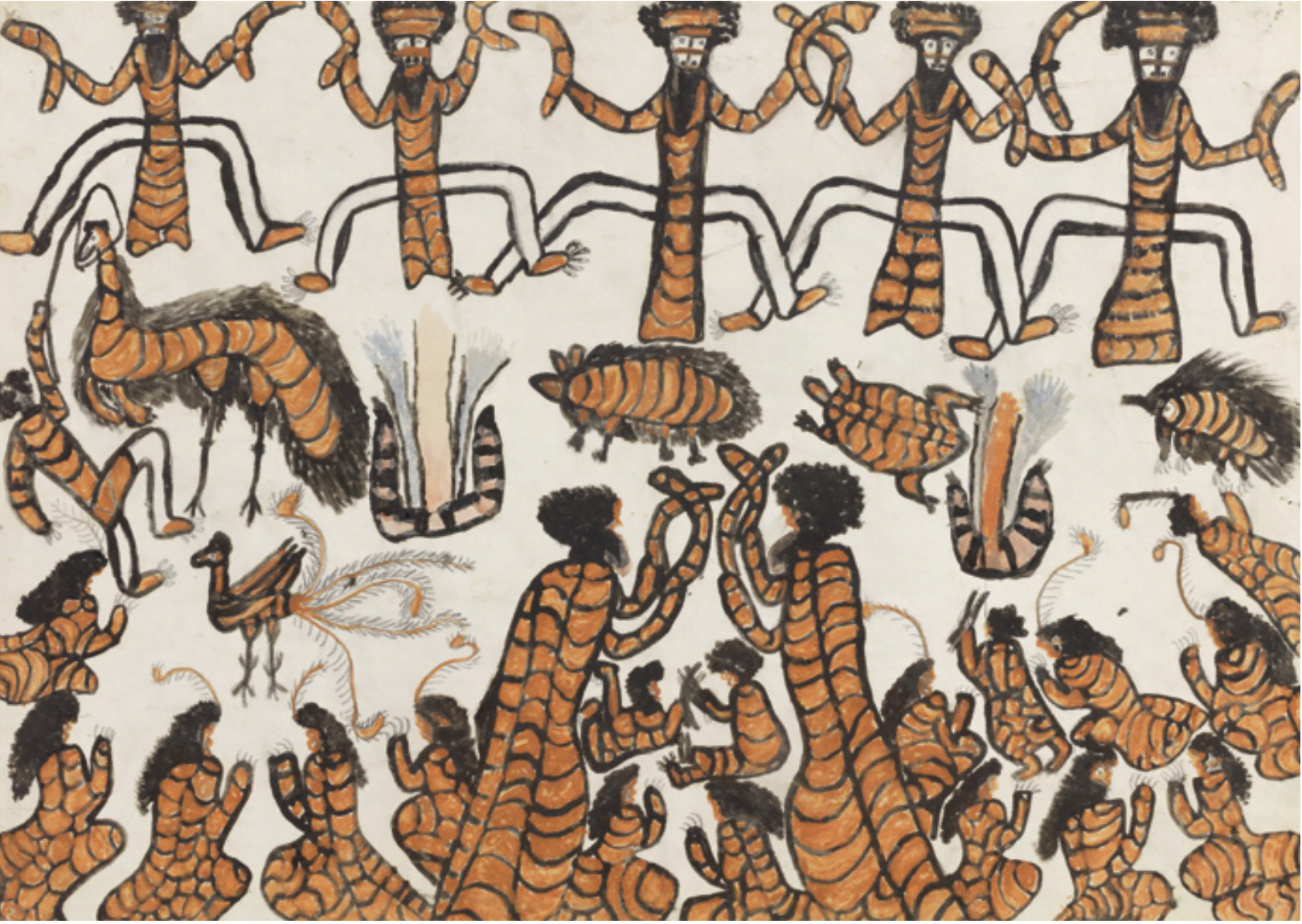

(Wurundjeri Ngurungaeta) Ceremony c. 1895

Art Gallery of Ballarat Collection Gift of Mrs Anne Fraser Bon, 1934

1. The term Blak was first coined by Erub/Mer (Torres Strait) and K’ua K’ua (Cape York) woman Destiny Deacon and is now widely used by First Peoples community as a reclaiming of colonialist language to create space of self-definition and self-expression of Indigeneity.