John Wolseley

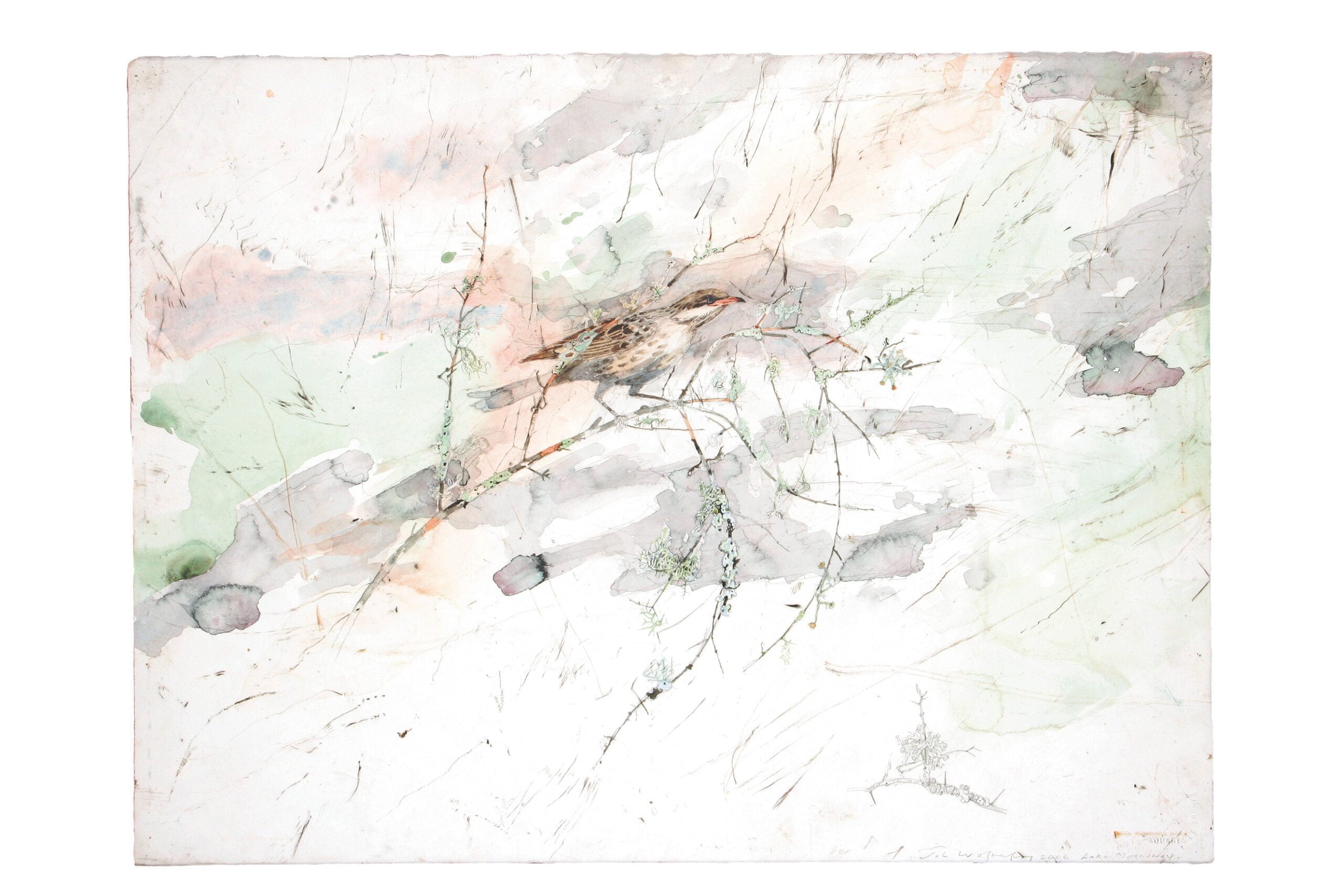

The walk caused me to evolve or push in another direction a particular kind of drawing that I call ‘frottage’, in which I move sheets of paper against and within the forms of the landscape after fire. In a sense both the landscape and artist are making the work – linking different patterns of growth and the juxtaposition of body and tree in a kind of awkward dance.

Making my way through the Cobbobonee Forest, I found myself moving through a tall vertical geography – feet in forest litter, body against burnt trunks and branches, arms grasping branches as one stumbles over uneven terrain, one’s head often up there in the clouds with other flying creatures.

The twigs and branches drag, stipple and scrape with their own inimitable sound across the paper. These marks have a strong aural quality akin to a musical score and I have found that there is a mysterious synergy between these notations and the songs of the birds of that habitat.

John Wolseley

Interested in the poetics of time and the impact of non-indigenous people and plants on Australian land and nature, Wolseley makes artwork in collaboration with the natural world. Gestural marks made with carbonised twigs and branches are interspersed with closely observed drawings of native flora and fauna in fields of coloured wash to form a broad, composite and shifting landscape. In these hybrid images, Wolseley prompts us to think beyond the limitations of human time and to reflect on how we use and experience land.

Interview with John Wolseley

Why was it important for you to participate in the Great South West Walk Art Project and undertake this journey?

It was important for me for several reasons. It seemed such an interesting group of participants. So often I am asked to do group things in the outback, which are heavily biased towards landscape painting, and for some reason there tends to be an over preponderance of ‘older’ often heavily male artists. This particular group by having an intelligent gender mix , and different disciplines (textile , jewellery, sculpture video etc.) promised to have an original and less conventional approach to working with land. Did you have any preconceived ideas or plans for your work before embarking on the Walk? I did have some plans, but as so often happens, the dynamic of the actual walk took over and I found new ways of expressing the marvellous landscape forms through which we passed; and these plans were jettisoned.

How would you describe your artistic practice from concept to making?

This question rather relates to the previous one. Because my practice often springs directly from the land or environment in which I find myself the concept and the making all evolve from a direct experience and immersion in a particular place. Usually I do masses of looking, investigating, and listening to what is special about that place. So for instance, in the forest I was mesmerised by the movement, song and character of the Bassian Thrushes. I drew them fossicking in the leaf litter. And I continued my interest in the nature of marks made by rubbing paper against burnt trees and shrubs. The burnt bark of the Messmate had a lovely soft powdery quality.

You have said that your artistic practice moved in a different direction during the Walk. How? I have always wanted – and often failed – to try and give a sense of what it is like to move through a forest. Often in the past I have, I think, given a sense of how the human body negotiates scrubland or desert. In a way the picture plane lends itself to being a kind of stretch of land – empty areas punctuated with different incidents; a tree stump here or an animal track there. But how to convey the ‘withiness,’ the ‘enclosedness’ of being deep within trees? Scrambling, climbing, swinging through the Cobboboonee Forest invited me try and convey just those modes of movement. The work about this in the show does I hope give a sense of feet in the leaf litter, arms grasping the branches, and in the top drawings in the installation the feeling that one’s head is up there in the canopy.

What were the major challenges you faced on the Walk?

The main challenge was given my need to make work as I dwell in a place. How could I do this at the same time as walking 200 or so kilometres over that time? I explained when we were planning the Walk how for someone like me there just was too much walking! So I was extremely naughty – claimed old age as an excuse – and peeled off for spells of two or three days so could stay in the one place for longer.

What do you hope the viewer will take away from your work and the exhibition?

I hope the viewer will get some sense of my excitement and passion when experiencing kinds of country new to me. The fact is that most work about landscape by non-indigenous artists in Australia is mostly done within a day car’s drive from the big metropolises. There are vast and magical areas of country crying out to be celebrated in song, dance, paint and textile. I hope this show will demonstrate how a group of gifted practitioners have done just that.

Which artists have been influential throughout your career?

Paul Nash, Samuel Palmer, J.M. Turner, Eugene Von Guerard, Ian Fairweather, Mark Tobey, Fiona Hall, Bea Maddock and Fred Williams.

John Wolseley is represented by Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery (Sydney) and Australian Galleries (Melbourne)

2007The walk caused me to evolve or push in another direction a particular kind of drawing that I call ‘frottage’, in which I move sheets of paper against and within the forms of the landscape after fire. In a sense both the landscape and artist are making the work – linking different patterns of growth and the juxtaposition of body and tree in a kind of awkward dance.

Making my way through the Cobbobonee Forest, I found myself moving through a tall vertical geography – feet in forest litter, body against burnt trunks and branches, arms grasping branches as one stumbles over uneven terrain, one’s head often up there in the clouds with other flying creatures.

The twigs and branches drag, stipple and scrape with their own inimitable sound across the paper. These marks have a strong aural quality akin to a musical score and I have found that there is a mysterious synergy between these notations and the songs of the birds of that habitat.

John Wolseley

Interested in the poetics of time and the impact of non-indigenous people and plants on Australian land and nature, Wolseley makes artwork in collaboration with the natural world. Gestural marks made with carbonised twigs and branches are interspersed with closely observed drawings of native flora and fauna in fields of coloured wash to form a broad, composite and shifting landscape. In these hybrid images, Wolseley prompts us to think beyond the limitations of human time and to reflect on how we use and experience land.

Interview with John Wolseley

Why was it important for you to participate in the Great South West Walk Art Project and undertake this journey?

It was important for me for several reasons. It seemed such an interesting group of participants. So often I am asked to do group things in the outback, which are heavily biased towards landscape painting, and for some reason there tends to be an over preponderance of ‘older’ often heavily male artists. This particular group by having an intelligent gender mix , and different disciplines (textile , jewellery, sculpture video etc.) promised to have an original and less conventional approach to working with land. Did you have any preconceived ideas or plans for your work before embarking on the Walk? I did have some plans, but as so often happens, the dynamic of the actual walk took over and I found new ways of expressing the marvellous landscape forms through which we passed; and these plans were jettisoned.

How would you describe your artistic practice from concept to making?

This question rather relates to the previous one. Because my practice often springs directly from the land or environment in which I find myself the concept and the making all evolve from a direct experience and immersion in a particular place. Usually I do masses of looking, investigating, and listening to what is special about that place. So for instance, in the forest I was mesmerised by the movement, song and character of the Bassian Thrushes. I drew them fossicking in the leaf litter. And I continued my interest in the nature of marks made by rubbing paper against burnt trees and shrubs. The burnt bark of the Messmate had a lovely soft powdery quality.

You have said that your artistic practice moved in a different direction during the Walk. How? I have always wanted – and often failed – to try and give a sense of what it is like to move through a forest. Often in the past I have, I think, given a sense of how the human body negotiates scrubland or desert. In a way the picture plane lends itself to being a kind of stretch of land – empty areas punctuated with different incidents; a tree stump here or an animal track there. But how to convey the ‘withiness,’ the ‘enclosedness’ of being deep within trees? Scrambling, climbing, swinging through the Cobboboonee Forest invited me try and convey just those modes of movement. The work about this in the show does I hope give a sense of feet in the leaf litter, arms grasping the branches, and in the top drawings in the installation the feeling that one’s head is up there in the canopy.

What were the major challenges you faced on the Walk?

The main challenge was given my need to make work as I dwell in a place. How could I do this at the same time as walking 200 or so kilometres over that time? I explained when we were planning the Walk how for someone like me there just was too much walking! So I was extremely naughty – claimed old age as an excuse – and peeled off for spells of two or three days so could stay in the one place for longer.

What do you hope the viewer will take away from your work and the exhibition?

I hope the viewer will get some sense of my excitement and passion when experiencing kinds of country new to me. The fact is that most work about landscape by non-indigenous artists in Australia is mostly done within a day car’s drive from the big metropolises. There are vast and magical areas of country crying out to be celebrated in song, dance, paint and textile. I hope this show will demonstrate how a group of gifted practitioners have done just that.

Which artists have been influential throughout your career?

Paul Nash, Samuel Palmer, J.M. Turner, Eugene Von Guerard, Ian Fairweather, Mark Tobey, Fiona Hall, Bea Maddock and Fred Williams.

John Wolseley is represented by Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery (Sydney) and Australian Galleries (Melbourne)

2007