James Morrison

Born in Papua New Guinea in 1959, James Morrison moved to Melbourne in 1972 and currently lives and works in Sydney. He has exhibited widely and his work is included in a number of public and private collections.

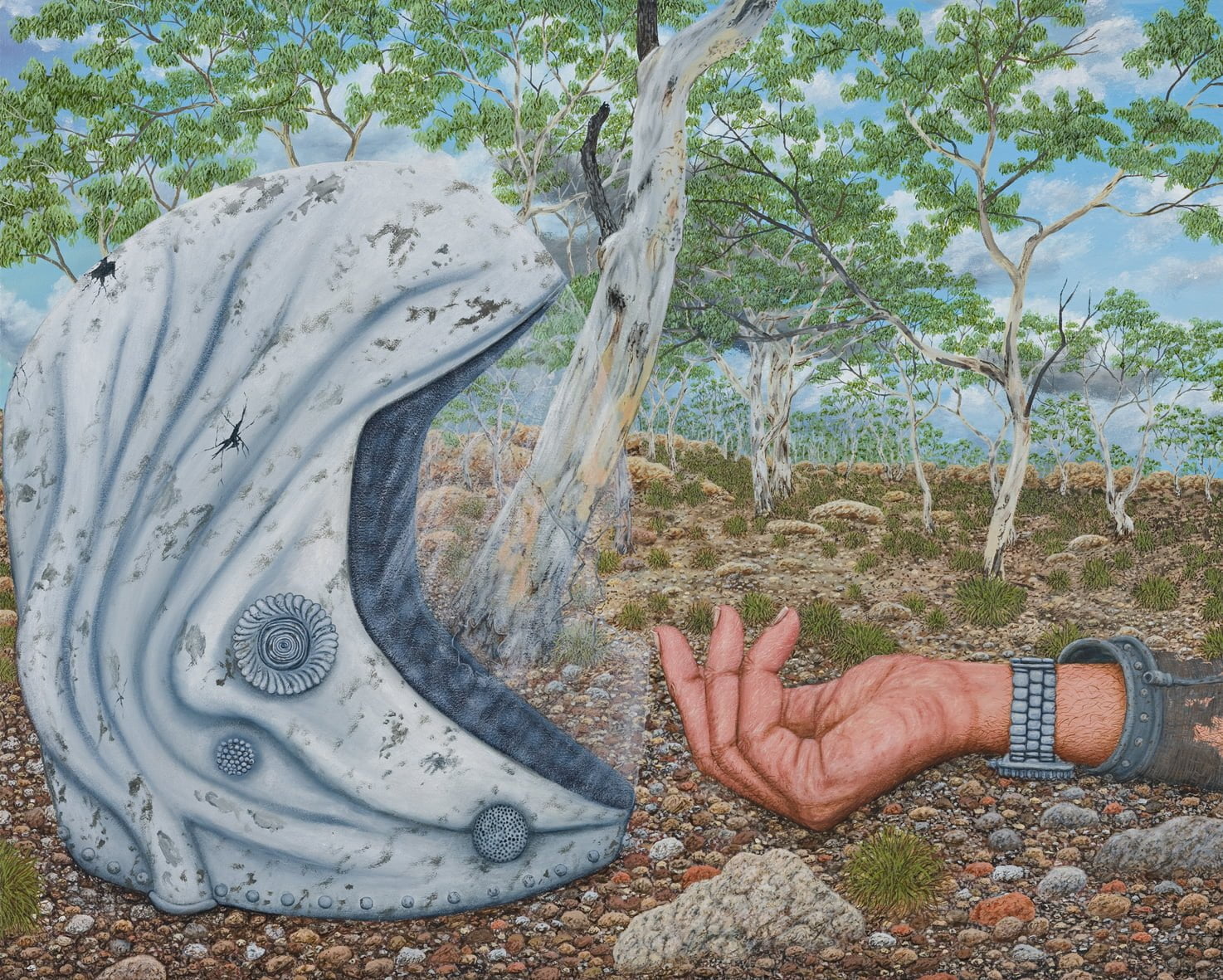

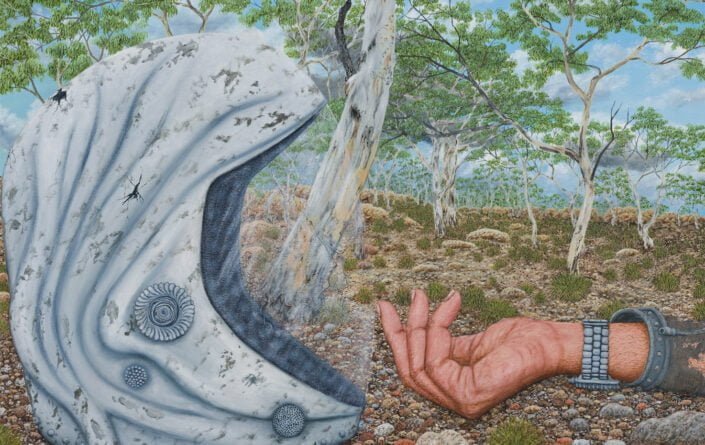

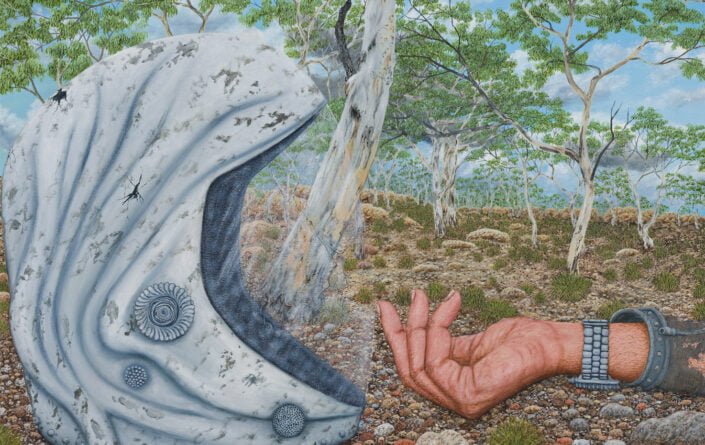

Morrison’s landscapes and histories draw from a wide range of sources and cultural references, defying chronology and operating according to their own idiosyncratic logic, the artist’s unexpected and whimsical combinations evoking children’s stories and fantasy novels. Morrison’s monumental painting, Freeman Dyson, created especially for The enchanted forest, features an Antipodean landscape that fluctuates between a roadside reserve and a future interplanetary space colony.

Interview with James Morrison

Born in Papua New Guinea in 1959, James Morrison moved to Melbourne in 1972 and currently lives and works in Sydney. He has exhibited widely and his work is included in a number of public and private collections.

Morrison’s landscapes and histories draw from a wide range of sources and cultural references, defying chronology and operating according to their own idiosyncratic logic, the artist’s unexpected and whimsical combinations evoking children’s stories and fantasy novels. Morrison’s monumental painting, Freeman Dyson, created especially for The enchanted forest, features an Antipodean landscape that fluctuates between a roadside reserve and a future interplanetary space colony.

You were born in Papua New Guinea (PNG). Was this a major influence in terms of the lush, exotic and vivid landscapes that you depict in your works?

I was brought up in a family with a very keen interest in all aspects of the natural world. A lot of time was spent in the bush either bird watching or finding wildflowers. In New Guinea the natural world was very much a part of the national people either for food or adornment. I think this had a very large influence on me, the stories and myths that are absorbed as a child. It was here also that I think the merging of the imaginary or mythic world and the natural world happened, it was part of the culture and part of life. Throughout your career you have been able to beautifully merge the imaginary realm with the natural world in epic narratives that also meditate on the environment.

Being brought up in PNG has had a huge influence on me, especially in terms of how I think about the natural world. The merging between myth and reality, where animals assume human qualities and humans adopt animal characters. The colours and the rich drama of landscape are always in the background even when I am painting the Australian bush. How would you describe your artistic practice from concept to making?

When making a painting, I always know what I want the end result to be. I am quite often disappointed in terms of technique and skill in realising what I want. And also aspects of the story can change and be enlarged along the way but basically it’s just trying to get my thoughts down onto the canvas.

Did you have any preconceived ideas or plans for your painting, Freeman Dyson (2008), which was specifically made for The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers?

My plans for the painting were to create a world were time had either slowed right down or stopped. The figure of a man could have been lying there 10 minutes or 400 years. The only thing moving are the crows and magpies fossicking through the remnants of clocks, watches and robotic parts. I wanted a feeling of stillness, a backwater in time.

Freeman Dyson taps into gothic storytelling elements such as the ‘fallen world’, the exile of the hero or protagonist, the threat of terror, as well as the exploration of the sublime and the supernatural. What is it about Freeman Dyson, the renowned physicist and his theories on futurism, space colonies, genetic engineering and the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence that inspired you to make this work?

By using Freeman Dyson’s name I realised I was opening up the work to a lot of readings. It was an interest in the man and the way he thought rather than any of his specific theories, although they are all appealing – of taking a remnant of an idea of him and stranding it here in this place and letting those stories play out or be teased out by the crows and magpies. He is still alive and in his 90s I think, a very fascinating man.

What was the greatest challenge for you when making Freeman Dyson?

I felt my greatest challenge when making the painting was to get the figure or his face just right. In a way it is a portal to the painting so the face had to show intelligence but also be neutral enough to be easily traversed.

Did you find it difficult to develop a sci-fi twist in the gothic genre?

No. My work always seems to have a slightly disjointed or unworldly feel to it so really it is just a natural progression

Scientists generally like to divide themselves into two groups: ’Birds’ who have a God’s-eye view of the world and ‘Frogs’ who spend their time in the mud. I recently read an interview with Freeman Dyson where he likened himself to a ‘Frog’ because he preferred to explore from the ground up. In a lot of ways, there’s a really nice juxtaposition there with your Freeman Dyson painting as its perspective starts from the ground up – like so many of your works that provide an insect’s eye view. Can you please explain why this perspective is important for you as an entry point for your narratives.

The perspective from the ground is important to me because I think, firstly, it adds another layer or depth to the work. The idea of worlds within worlds gradually going down to a finite core.

Also it is a perspective from lying down, a lazy artist or a child’s view. I also like the idea of when you are lying down reading a book and you look up and for a moment you are in two worlds, the one of the book and the real one around you.

What do you hope the viewer will take away from your work and the exhibition, The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers?

The stories in the work are open enough so maybe people will take away their own endings or maybe just ponder for a moment [on] twists of time and circumstance.

2008Born in Papua New Guinea in 1959, James Morrison moved to Melbourne in 1972 and currently lives and works in Sydney. He has exhibited widely and his work is included in a number of public and private collections.

Morrison’s landscapes and histories draw from a wide range of sources and cultural references, defying chronology and operating according to their own idiosyncratic logic, the artist’s unexpected and whimsical combinations evoking children’s stories and fantasy novels. Morrison’s monumental painting, Freeman Dyson, created especially for The enchanted forest, features an Antipodean landscape that fluctuates between a roadside reserve and a future interplanetary space colony.

Interview with James Morrison

Born in Papua New Guinea in 1959, James Morrison moved to Melbourne in 1972 and currently lives and works in Sydney. He has exhibited widely and his work is included in a number of public and private collections.

Morrison’s landscapes and histories draw from a wide range of sources and cultural references, defying chronology and operating according to their own idiosyncratic logic, the artist’s unexpected and whimsical combinations evoking children’s stories and fantasy novels. Morrison’s monumental painting, Freeman Dyson, created especially for The enchanted forest, features an Antipodean landscape that fluctuates between a roadside reserve and a future interplanetary space colony.

You were born in Papua New Guinea (PNG). Was this a major influence in terms of the lush, exotic and vivid landscapes that you depict in your works?

I was brought up in a family with a very keen interest in all aspects of the natural world. A lot of time was spent in the bush either bird watching or finding wildflowers. In New Guinea the natural world was very much a part of the national people either for food or adornment. I think this had a very large influence on me, the stories and myths that are absorbed as a child. It was here also that I think the merging of the imaginary or mythic world and the natural world happened, it was part of the culture and part of life. Throughout your career you have been able to beautifully merge the imaginary realm with the natural world in epic narratives that also meditate on the environment.

Being brought up in PNG has had a huge influence on me, especially in terms of how I think about the natural world. The merging between myth and reality, where animals assume human qualities and humans adopt animal characters. The colours and the rich drama of landscape are always in the background even when I am painting the Australian bush. How would you describe your artistic practice from concept to making?

When making a painting, I always know what I want the end result to be. I am quite often disappointed in terms of technique and skill in realising what I want. And also aspects of the story can change and be enlarged along the way but basically it’s just trying to get my thoughts down onto the canvas.

Did you have any preconceived ideas or plans for your painting, Freeman Dyson (2008), which was specifically made for The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers?

My plans for the painting were to create a world were time had either slowed right down or stopped. The figure of a man could have been lying there 10 minutes or 400 years. The only thing moving are the crows and magpies fossicking through the remnants of clocks, watches and robotic parts. I wanted a feeling of stillness, a backwater in time.

Freeman Dyson taps into gothic storytelling elements such as the ‘fallen world’, the exile of the hero or protagonist, the threat of terror, as well as the exploration of the sublime and the supernatural. What is it about Freeman Dyson, the renowned physicist and his theories on futurism, space colonies, genetic engineering and the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence that inspired you to make this work?

By using Freeman Dyson’s name I realised I was opening up the work to a lot of readings. It was an interest in the man and the way he thought rather than any of his specific theories, although they are all appealing – of taking a remnant of an idea of him and stranding it here in this place and letting those stories play out or be teased out by the crows and magpies. He is still alive and in his 90s I think, a very fascinating man.

What was the greatest challenge for you when making Freeman Dyson?

I felt my greatest challenge when making the painting was to get the figure or his face just right. In a way it is a portal to the painting so the face had to show intelligence but also be neutral enough to be easily traversed.

Did you find it difficult to develop a sci-fi twist in the gothic genre?

No. My work always seems to have a slightly disjointed or unworldly feel to it so really it is just a natural progression

Scientists generally like to divide themselves into two groups: ’Birds’ who have a God’s-eye view of the world and ‘Frogs’ who spend their time in the mud. I recently read an interview with Freeman Dyson where he likened himself to a ‘Frog’ because he preferred to explore from the ground up. In a lot of ways, there’s a really nice juxtaposition there with your Freeman Dyson painting as its perspective starts from the ground up – like so many of your works that provide an insect’s eye view. Can you please explain why this perspective is important for you as an entry point for your narratives.

The perspective from the ground is important to me because I think, firstly, it adds another layer or depth to the work. The idea of worlds within worlds gradually going down to a finite core.

Also it is a perspective from lying down, a lazy artist or a child’s view. I also like the idea of when you are lying down reading a book and you look up and for a moment you are in two worlds, the one of the book and the real one around you.

What do you hope the viewer will take away from your work and the exhibition, The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers?

The stories in the work are open enough so maybe people will take away their own endings or maybe just ponder for a moment [on] twists of time and circumstance.

2008