Deborah Klein

Deborah Klein was born in 1951. Her work has been exhibited widely locally and internationally and is represented in numerous public and private collections. She holds a Master of Arts (Visual Arts) from Monash University, Gippsland.

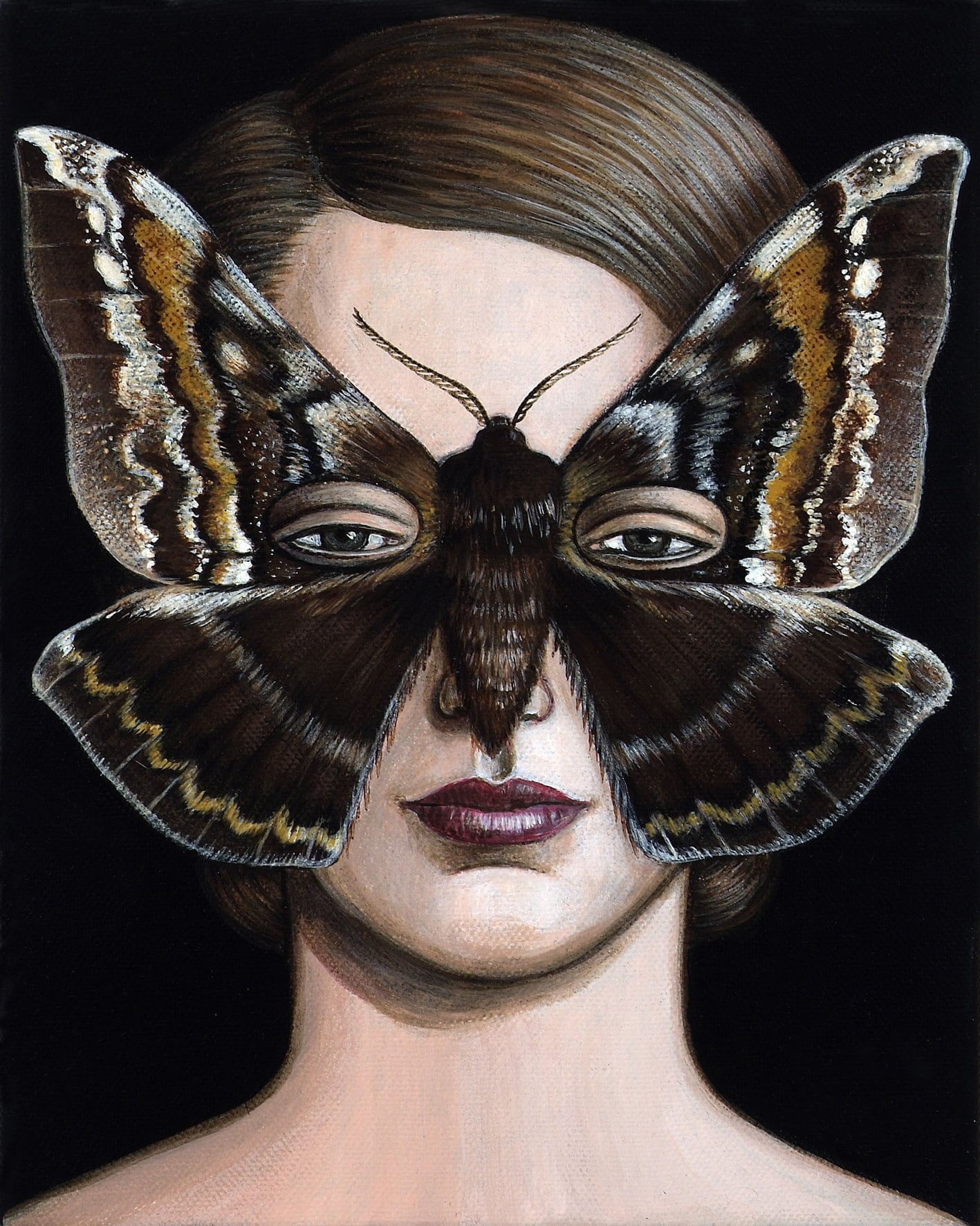

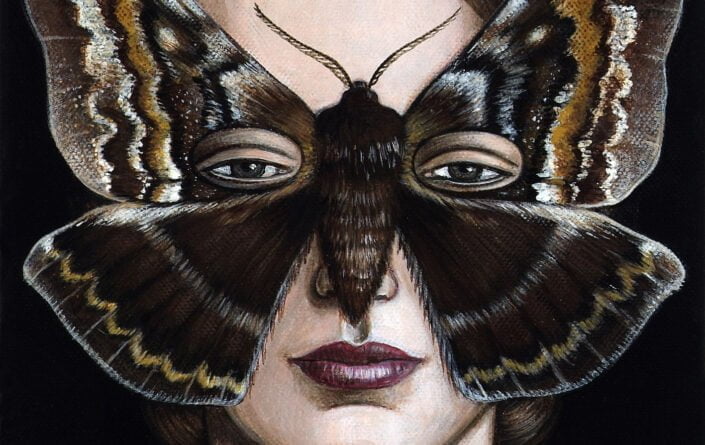

Klein’s immaculately coiffed women are as exquisitely decorative, and as perfectly still, as the butterflies that accompany them. As though pinned by a spell these repressed Rapunzels dare not let down their hair, trapped by manners and social status, coveted and collected in ivory towers.

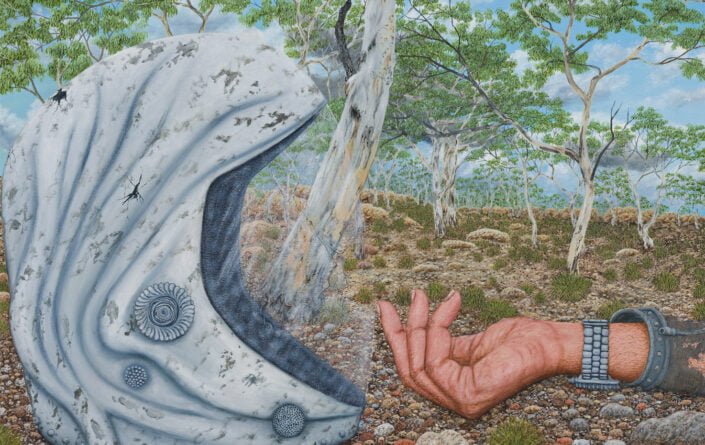

The iconography within Klein’s new works for The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers will be derived from the insect world, utilising a range of luminous, jewel-like colours.

Interview with Deborah Klein

Deborah Klein was born in 1951. Her work has been exhibited locally and internationally and is represented in numerous public and private collections. She holds a Master of Arts (Visual Arts) from Monash University, Gippsland. Referencing historical representations of women, social mores and manners and the science of taxonomy, Klein has developed a distinctive personal iconography with which to investigate and challenge representations of femininity. Swarm and Moth masks, Klein’s body of works for The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers, draw inspiration from the insect world. Her immaculately coiffed women are as exquisitely decorative, still and collectable, as the luminous, jewel-like butterflies and moths that accompany them.

How would you describe your artistic practice from concept to making?

My practice is equally divided between drawing (both as a process and medium), printmaking and painting. Of these, drawing is by far the most important and essential, as I believe that it underpins all areas of art practice. Both before and during the development of any project I tend to conduct fairly extensive research.

How did you research and select the moths and butterflies in your works?

By the time I finished Swarm I had accumulated a small collection of books on moths and butterflies. These went on to provide a firm basis for the early Moth masks works. But the key source for the majority of the moth masks was the CSIRO website . It is a real treasure trove. I also visited the Melbourne Museum in order to examine examples of moths and butterflies firsthand. Are the moths and butterflies in your works Australian?

The majority of butterflies and moths are from the Indo-Australasian region. With a couple of exceptions, so are the moths. For example, Euchloron megaera is from Africa. It was only when the Moth masks project was under way that I discovered the CSIRO website. Had I found it earlier, and discovered what magnificent species of moths are to be found in this region, I would have only used moths from the southern region – especially Australia – in my work. Do they have particular symbolic meanings? I chose individual moths and butterflies for purely aesthetic reasons. Any symbolic meaning comes from the work itself.

Throughout your career you have examined gender and identity in both a social and cultural context while often playing with the use of symbols, such as hair and ornamentation. What were you seeking to explore (or further develop) in both bodies of work in The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers?

First and foremost, I welcomed the opportunity to incorporate storytelling more fully into my work once more. In recent years the imagery had become increasingly minimal and so, correspondingly, had its narrative content.

Swarm had its genesis in a body of work titled Private Collection, which I exhibited at Australian Galleries in Melbourne in 2000. Although the exhibition also comprised relief prints and drawings, the key works were a series of small multi-paneled canvases. A number of these utilised oval shapes, partly as a reference to Elizabethan portrait miniatures. The exhibition’s deliberately ambiguous title could just as easily have referred to the paintings’ anonymous subjects as to the works as a whole. These women were like the intricately braided locks of hair in Victorian mourning jewellery that initially inspired their hairstyles – contained and entrapped, reduced to little more than collector’s items.

The idea for Swarm immerged about halfway through this project, partly because thematically it was a natural extension of the work in progress. At this time I was also given a copy of A. S. Byatt’s novel Angels and Insects. It was this book that really set me firmly on the path to Swarm.

Was it a conscious decision to make both works distinctly opposite in that the Swarm (2002) portraits turn their backs on the viewer while the women in the Moth masks series (2007) face the viewer, and that there are butterflies versus moths, day versus night, as well as beauty versus mortality?

No, it was not a conscious decision, despite my longtime fascination with the idea of opposites. Having said that, I have to admit that for some time I had wanted to turn my subjects around to face the viewer once more. But it was something that couldn’t be forced – it had to happen for a reason. Swarm predates the Moth masks by several years and it was definitely a point of departure for the new work. Revisiting it led to wider, more extensive research into spiders, bugs and insects. But it was the discovery of the moths that really fired my imagination. The markings on the wings of some moths already suggest a pair of staring eyes. To turn them into masks was, once again, almost a natural extension. As an artist I also work very much on an intuitive level and if something potentially significant emerges – like the idea of opposites – it is important to try to reinforce it, build on it, and if possible, take it further – but never try to force it.

How long have you been fascinated with butterflies and moths? Why?

My interest in butterflies began with Swarm. Their jewel-like colours and scale perfectly suited the ideas I was exploring in my imagery at that time, providing the means of further developing the idea of a trapped individual.

The moth mask paintings were made especially for this show and are a relatively new discovery that has enabled me to take my work in an entirely new direction. I find moths much more fascinating than butterflies, perhaps because we tend to think of them as creatures of the night, which for me adds further to their mystique.

Swarm evokes the notion of collecting from the thrill of the chase to the need to classify, label and display these trophies from the hunt. Can you please explain your intention for this work and the importance of the arrangement of the 32 canvases that make up Swarm.

Like all my work it is open to individual interpretation. The 32 canvases were actually intended to form an oval, but instead look more like a diamond. While the work intentionally recalls a display of insect trophies on the wall of a collector, it could equally be a flight formation of winged creatures.

To me, Swarm is very reminiscent of a butterfly collection on the walls of a lepidopterist’s study and even evokes the classic John Fowles novel, The Collector.

I have read several of John Fowles’ novels, and although I was very aware of The Collector and its theme, I had never read it. Until recently I had never seen the equally celebrated movie. When I began the Moth masks series I managed to track down the film on DVD. It is a fine film – still very powerful – and powerfully disturbing.

How did the Moth masks series evolve? Even though the seductive portraits stare directly at the viewer, each sitter’s true identity is disguised by an individual moth mask. What was your intention?

While not a direct influence, the film The Collector reinforced some of my own ideas, as did Angels and Insects, which I re-read in the early stages of the moth mask paintings.

The notion of ‘looking over the overlooked’ has always been central to my practice. Moths are a perfect metaphor for this. Unfairly considered to be drab in comparison to butterflies, they can be every bit as bright and beautiful.

Another misconception is that all moths are night fliers. But it is this mythology and the secret existence that it suggests that partly directed this work. The moths’ functions as masks or disguises are an extension of that.

Despite their masks – maybe even because of them – I have aimed to portray each of the women as a distinct individual. A visitor to the studio commented that it was as if they all had souls. I deliberately chose individual moths to match each of the subjects – not as fashion accessories, but as extensions of themselves. Were you also exploring metamorphosis?

The narrative content of the work remains openended. As a further extension of the idea of storytelling, however, I wrote a very short story based on the Moth masks. But I must stress that it is not meant to be the last word in how the works should be read. The story, which I will eventually develop into an artist’s book, is about metamorphosis. What do you hope the viewer will take away from your work and the exhibition, The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers?

I hope that some of the images will not only remain with them but will fire their imaginations enough to make up their own stories about them.

2008Deborah Klein was born in 1951. Her work has been exhibited widely locally and internationally and is represented in numerous public and private collections. She holds a Master of Arts (Visual Arts) from Monash University, Gippsland.

Klein’s immaculately coiffed women are as exquisitely decorative, and as perfectly still, as the butterflies that accompany them. As though pinned by a spell these repressed Rapunzels dare not let down their hair, trapped by manners and social status, coveted and collected in ivory towers.

The iconography within Klein’s new works for The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers will be derived from the insect world, utilising a range of luminous, jewel-like colours.

Interview with Deborah Klein

Deborah Klein was born in 1951. Her work has been exhibited locally and internationally and is represented in numerous public and private collections. She holds a Master of Arts (Visual Arts) from Monash University, Gippsland. Referencing historical representations of women, social mores and manners and the science of taxonomy, Klein has developed a distinctive personal iconography with which to investigate and challenge representations of femininity. Swarm and Moth masks, Klein’s body of works for The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers, draw inspiration from the insect world. Her immaculately coiffed women are as exquisitely decorative, still and collectable, as the luminous, jewel-like butterflies and moths that accompany them.

How would you describe your artistic practice from concept to making?

My practice is equally divided between drawing (both as a process and medium), printmaking and painting. Of these, drawing is by far the most important and essential, as I believe that it underpins all areas of art practice. Both before and during the development of any project I tend to conduct fairly extensive research.

How did you research and select the moths and butterflies in your works?

By the time I finished Swarm I had accumulated a small collection of books on moths and butterflies. These went on to provide a firm basis for the early Moth masks works. But the key source for the majority of the moth masks was the CSIRO website . It is a real treasure trove. I also visited the Melbourne Museum in order to examine examples of moths and butterflies firsthand. Are the moths and butterflies in your works Australian?

The majority of butterflies and moths are from the Indo-Australasian region. With a couple of exceptions, so are the moths. For example, Euchloron megaera is from Africa. It was only when the Moth masks project was under way that I discovered the CSIRO website. Had I found it earlier, and discovered what magnificent species of moths are to be found in this region, I would have only used moths from the southern region – especially Australia – in my work. Do they have particular symbolic meanings? I chose individual moths and butterflies for purely aesthetic reasons. Any symbolic meaning comes from the work itself.

Throughout your career you have examined gender and identity in both a social and cultural context while often playing with the use of symbols, such as hair and ornamentation. What were you seeking to explore (or further develop) in both bodies of work in The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers?

First and foremost, I welcomed the opportunity to incorporate storytelling more fully into my work once more. In recent years the imagery had become increasingly minimal and so, correspondingly, had its narrative content.

Swarm had its genesis in a body of work titled Private Collection, which I exhibited at Australian Galleries in Melbourne in 2000. Although the exhibition also comprised relief prints and drawings, the key works were a series of small multi-paneled canvases. A number of these utilised oval shapes, partly as a reference to Elizabethan portrait miniatures. The exhibition’s deliberately ambiguous title could just as easily have referred to the paintings’ anonymous subjects as to the works as a whole. These women were like the intricately braided locks of hair in Victorian mourning jewellery that initially inspired their hairstyles – contained and entrapped, reduced to little more than collector’s items.

The idea for Swarm immerged about halfway through this project, partly because thematically it was a natural extension of the work in progress. At this time I was also given a copy of A. S. Byatt’s novel Angels and Insects. It was this book that really set me firmly on the path to Swarm.

Was it a conscious decision to make both works distinctly opposite in that the Swarm (2002) portraits turn their backs on the viewer while the women in the Moth masks series (2007) face the viewer, and that there are butterflies versus moths, day versus night, as well as beauty versus mortality?

No, it was not a conscious decision, despite my longtime fascination with the idea of opposites. Having said that, I have to admit that for some time I had wanted to turn my subjects around to face the viewer once more. But it was something that couldn’t be forced – it had to happen for a reason. Swarm predates the Moth masks by several years and it was definitely a point of departure for the new work. Revisiting it led to wider, more extensive research into spiders, bugs and insects. But it was the discovery of the moths that really fired my imagination. The markings on the wings of some moths already suggest a pair of staring eyes. To turn them into masks was, once again, almost a natural extension. As an artist I also work very much on an intuitive level and if something potentially significant emerges – like the idea of opposites – it is important to try to reinforce it, build on it, and if possible, take it further – but never try to force it.

How long have you been fascinated with butterflies and moths? Why?

My interest in butterflies began with Swarm. Their jewel-like colours and scale perfectly suited the ideas I was exploring in my imagery at that time, providing the means of further developing the idea of a trapped individual.

The moth mask paintings were made especially for this show and are a relatively new discovery that has enabled me to take my work in an entirely new direction. I find moths much more fascinating than butterflies, perhaps because we tend to think of them as creatures of the night, which for me adds further to their mystique.

Swarm evokes the notion of collecting from the thrill of the chase to the need to classify, label and display these trophies from the hunt. Can you please explain your intention for this work and the importance of the arrangement of the 32 canvases that make up Swarm.

Like all my work it is open to individual interpretation. The 32 canvases were actually intended to form an oval, but instead look more like a diamond. While the work intentionally recalls a display of insect trophies on the wall of a collector, it could equally be a flight formation of winged creatures.

To me, Swarm is very reminiscent of a butterfly collection on the walls of a lepidopterist’s study and even evokes the classic John Fowles novel, The Collector.

I have read several of John Fowles’ novels, and although I was very aware of The Collector and its theme, I had never read it. Until recently I had never seen the equally celebrated movie. When I began the Moth masks series I managed to track down the film on DVD. It is a fine film – still very powerful – and powerfully disturbing.

How did the Moth masks series evolve? Even though the seductive portraits stare directly at the viewer, each sitter’s true identity is disguised by an individual moth mask. What was your intention?

While not a direct influence, the film The Collector reinforced some of my own ideas, as did Angels and Insects, which I re-read in the early stages of the moth mask paintings.

The notion of ‘looking over the overlooked’ has always been central to my practice. Moths are a perfect metaphor for this. Unfairly considered to be drab in comparison to butterflies, they can be every bit as bright and beautiful.

Another misconception is that all moths are night fliers. But it is this mythology and the secret existence that it suggests that partly directed this work. The moths’ functions as masks or disguises are an extension of that.

Despite their masks – maybe even because of them – I have aimed to portray each of the women as a distinct individual. A visitor to the studio commented that it was as if they all had souls. I deliberately chose individual moths to match each of the subjects – not as fashion accessories, but as extensions of themselves. Were you also exploring metamorphosis?

The narrative content of the work remains openended. As a further extension of the idea of storytelling, however, I wrote a very short story based on the Moth masks. But I must stress that it is not meant to be the last word in how the works should be read. The story, which I will eventually develop into an artist’s book, is about metamorphosis. What do you hope the viewer will take away from your work and the exhibition, The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers?

I hope that some of the images will not only remain with them but will fire their imaginations enough to make up their own stories about them.

2008