Subversive Craft as a Contemporary Art Strategy: Rethinking the Histories of Gender and Representation—

Anna Briers

Craftivism: Dissident Objects and Subversive Forms weaves together a range of themes within the matrix of the exhibition’s literal and metaphorical fabric. Using craft materials and techniques, many of the artists, such as Deborah Kelly, Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran, Paul Yore, Kate Just, Karen Black, Starlie Geikie and Tai Snaith, explore ideas concerning gender, sexuality, feminism or LGBTIQ+ politics, responding to histories of representation and creating new aesthetic forms of selfhood and rebellion.

Previously subordinated within art world hierarchies, craft has been a trending topic for the last decade, its processes and presence now seen in both popular culture and contemporary art circles. In Rozsika Parker’s seminal text The Subversive Stitch 1984, the feminist theorist argued that the historical divisions between art and craft, as well as their attributions of value, were bound up within the divisions of gender. Craft was associated with the defining and reinforcing of notions of femininity; it was considered a frivolous, decorative activity found in the domestic sphere. By contrast, painting and sculpture were considered more intellectual, masculine pursuits, produced for financial gain in the public domain.1 The artists in this exhibition leverage both traditional craft techniques and their associated readings in relation to gender constructs and representation. Concurrently, they reinscribe the value of craft as a powerful and subversive tactic within the canon of contemporary art.

Paradoxically, Parker also notes that, while historically the fine stitchery of upper-class ladies and the labour of the working classes became a ‘symbol and instrument of female subservience’, embroidery also became a way to negotiate the constraints of the feminine role.2 Within the scope of this seemingly oppressive pastime, women found a means of pleasure, empowerment and also resistance, a concept exemplified by artists of all genders in this exhibition, working in a contemporary context.

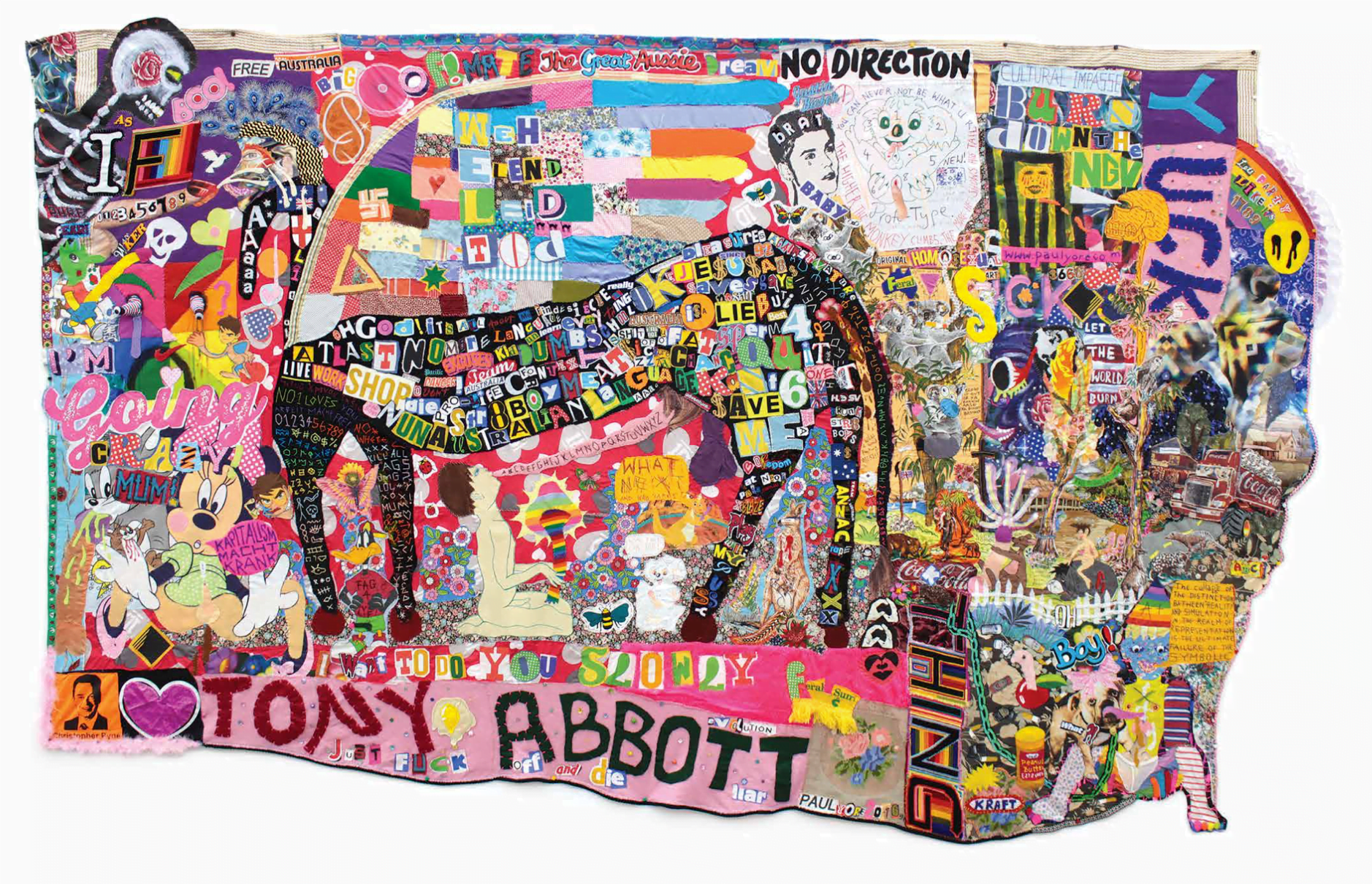

In the work of Paul Yore, the traditionally feminine textile practices of quilting and embroidery, along with assemblage, are employed to express queer male sexuality, national identity and the hyper-mediated overload of the internet age. Borrowing from the aesthetics of drag and Mardi Gras exuberance, Yore’s visual language incorporates a melange of text, imagery and junkshop accoutrements, realised in

the palette of a psychedelic rainbow.

1. Rozsika Parker, ‘The Creation of Femininity’, in The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine, Women’s Press, London, 1984, pp. 5–11.

2. Ibid.

Paul Yore. What a Fucking Horrid Mess 2016. Purchased with Ararat Rural City Council aquisition allocation, 2016. Ararat Gallery TAMA Collection. © the artist.

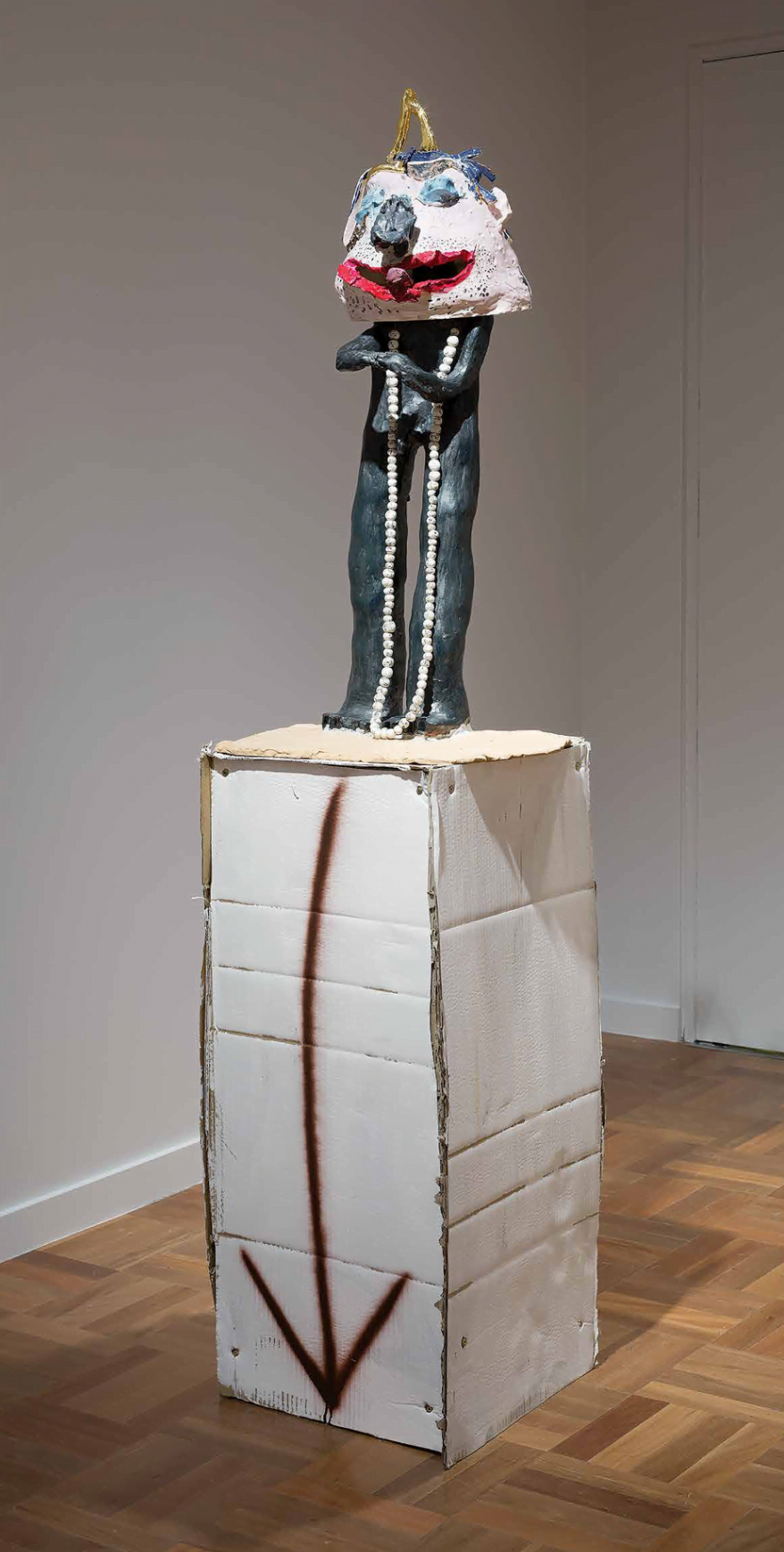

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran. Pewter dickhead 2 2015. Recipient of the 2015 Sidney Myer Fund Australian Ceramic Award. Shepparton Art Museum Collection. © the artist

In What a Horrid Fucking Mess 2016 and Art is Language 2017, Yore presents a deluge of imagery that acts as a coordinated attack on the viewer’s retina. In the first work, Australian fauna collides with images of global pop stars and cartoon characters. Queer sexual innuendo and personal reflections intermingle with an arsenal of corporate icons. Coca-Cola logos and Nike swooshes collide with swastikas, hearts and butterflies, short-circuiting their semiotic meanings.

Yore’s use of textiles subverts the gender stereotypes associated with the medium. Deeply layered, his work has the intrigue of a lavishly decorated men’s toilet stall located within a Country Women’s Association tea party. Yore’s use of appliqué, quilting, needlepoint and found embroidery has a disarming effect on the intensity of his subject matter.

This mesmerising combination elicits a multiplicity of readings, from queer expressions of sexuality to cultural critique. In one corner, a panel of text quotes cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard: ‘The collapse of the distinction between reality and simulation in the realm of representation is the ultimate failure of the symbolic.’3 This succinctly recalls the cultural context in which we find ourselves. ‘Fake news’ is the new norm, reality TV stars become world leaders, and the hyper-mediated reality of our internet age appears to blur the boundaries between truth and fiction.

3. See Jean Baudrillard’s treatise on the simulacra in Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Glaser, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1994.

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran is primarily known for his figurative ceramics practice. Often realised in monumental proportions, his works reference sources as diverse as pre- colonial Hindu devotional sculpture, Christianity and internet porn to explore a range of ideas, from religion and creation to homoeroticism and the notion of gender performance.

Pewter dickhead 2 2015 was originally presented as part of Archipelago in the 2015 Sidney Myer Fund Australian Ceramic Award. Unified by the concept of a group of islands, the installation included a cast of creatures with anthropomorphic tendencies or non-binary gender identities, exemplified by an androgynous figure adorned with a necklace, blue eye shadow and lipstick. The figure reads as an amplified version of one gender impersonating another, unable to be assigned a definitive category.

At its core, Nithiyendran’s work is performative.

A heightened theatricality is generated by his expressionist gestures as materials and processes appear exaggerated and hyperbolic – acting as performances of themselves. Viscous glazes ooze and spill over, resembling bodily excretions. Bulging abject forms gleam with seductive gold lustre glazes.4 Bold and irreverent, Nithiyendran explores the fluid and performative nature of gender by pushing the technical boundaries of the ceramic medium.

In this exhibition, Deborah Kelly disrupts art historical narratives around female representation through the medium of collage. Investigating the male gaze, Kelly’s video work LYING WOMEN 2016 employs cut-outs of women’s bodies from the pages of discarded art history books as a means to interrogate and rupture the artistic canon of the reclining nude. Set to an arresting soundtrack of women’s rhythmic breathing, historical representations of reclining nudes, such as Édouard Manet’s Olympia 1863, shuffle across the screen in stop-motion animation. These women are portrayed in classical poses typical of the genre. Arms are raised behind heads so as best to display breasts, while veiled gazes are directed submissively away from the presumed male spectator/owner beyond the frame.

Severed from their original contexts – the paintings and narrative fantasies into which they were cemented for centuries – the figures are now liberated from their previous status as sexual objects for passive consumption. Kelly relocates them into alternative narratives where they appear to have agency, interacting together in a manner that implies they have secret, independent lives and are rewriting the established patriarchal tropes of Western art history.

4. Anna Briers, ‘Subversion, Intervention and Extension. Clay in a Contemporary Context’, in 2015 Sidney Myer Fund Australian Ceramic Award (ex. cat.), Shepparton Art Museum, 2015, p. 12.

The artists in this exhibition leverage both traditional craft techniques and their associated readings in relation to gender constructs and representation. They reinscribe the value of craft as a powerful and subversive tactic within the canon of contemporary art.

Deborah Kelly. LYING WOMEN (still) 2016. Cinematography by Christian J Heinrich. Editor: Elliott Magen. Original score composed

by Evelyn Ida Morris. Soundscape: Adam Hulbert. © the artist, courtesy the artist.

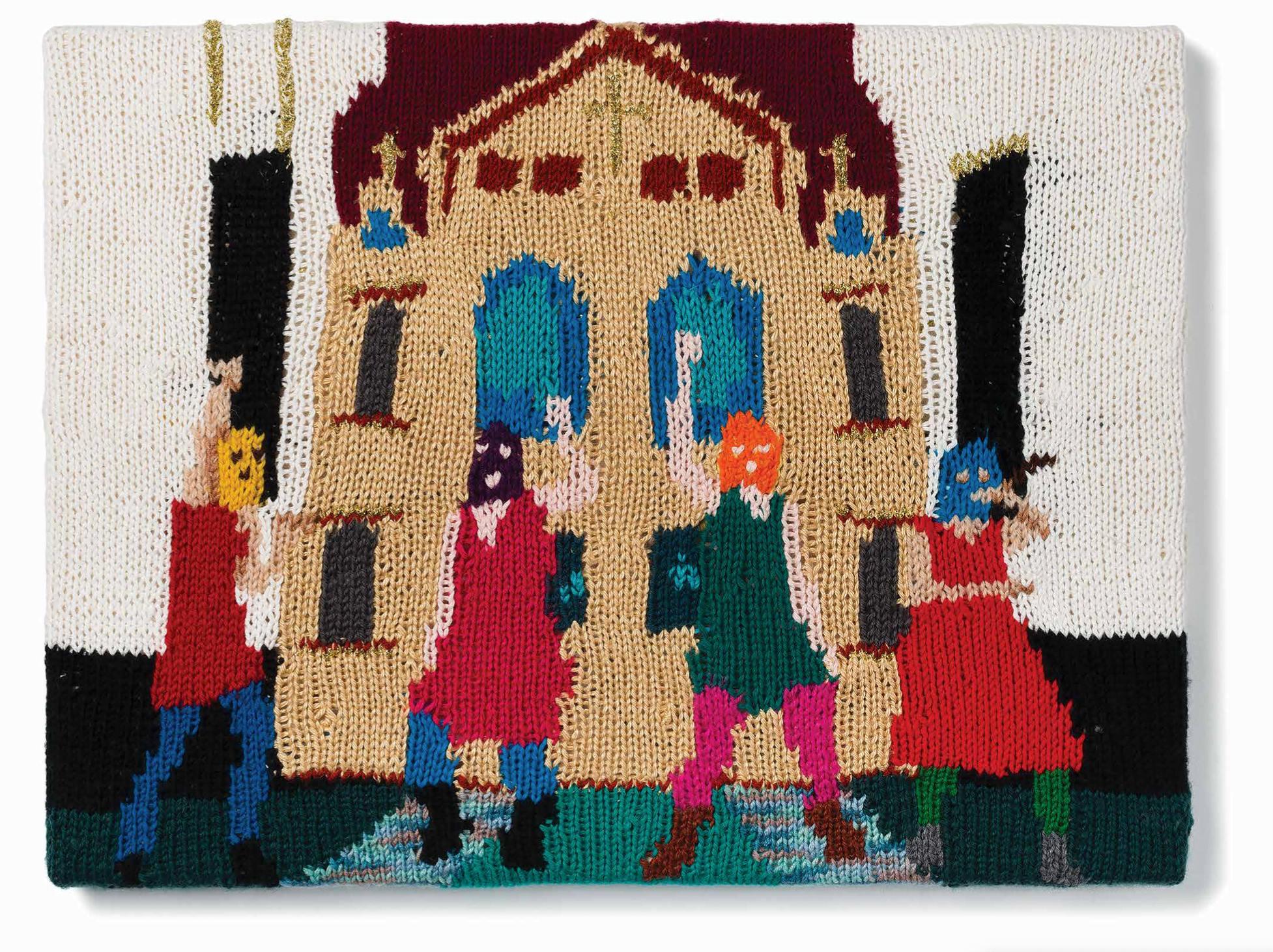

Kate Just’s practice also centres around feminist politics and issues relating to gender and representation. She is known for her large-scale collaborative knitting and crocheting projects that have resulted in protest banners such as HOPE 2013 and SAFE 2014. Imbuing the domestic and homely material of yarn with political intent, these works function as a means of symbolic resistance, combating domestic abuse and sexual violence through raising awareness.

In her Feminist Fan series 2015–17, Just has knitted a suite of wall works that pay homage to feminist artists and activist histories. The result of significant labour and devoted fandom, this body of work (shown here in part) portrays feminist

icons from 1920 to 2015. One image depicts infamous Melbourne craftivist Casey Jenkins, who ‘went viral’ in 2013 after a controversial vaginal knitting performance.5 Another depicts Russian activists Pussy Riot in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, where they performed their ‘punk prayer’. This performative intervention was perceived by the Russian establishment to be a very real threat to organised religion, homophobia and patriarchy. Three of the members were subsequently arrested and jailed by the Putin regime in 2012.

Extended in reach through social media platforms such as Instagram, the Feminist Fan series is enabled to simultaneously impart its

5. Casey Jenkins became an overnight YouTube sensation and feminist poster girl for her work Casting Off My Womb 2013, which has received 6 million views to date.

Kate Just. Feminist Fan #3 (Pussy Riot at Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, 2012) 2015. © the artist, courtesy the artist.

Photo: Simon Strong.

Starlie Geikie. Rapala, Standard, Tiles, Pennant, Ensign, We were river people 2012–13. © the artist, courtesy the artist.

Tai Snaith. A world of her own (Dramatic assemblage, Loose knit, Known history) 2018. © the artist, courtesy the artist.

Karen Black. Temporary arrangement – yellow in 3 parts 2017. © the artist, courtesy the artist, Sutton Gallery, Melbourne and

Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney / Singapore. Photo: Christian Capurro.

message within both actual and virtual domains. Replete with a series of descriptive hashtags, Just’s works expand on second-wave feminist strategies of collaboration and consciousness- raising while recalling the protest tactics of the #MeToo movement,6 co-opting the amplified power and connectivity of social networking in the internet age.

Tai Snaith has an expansive, multidisciplinary practice that encompasses ceramics, writing, curation, broadcasting and illustration. For this exhibition, she presents a selection of podcasts from an extensive series of conversations produced for Unfinished Business: Perspectives on Art and Feminism 2018 at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art. Featuring established female artists with craft practices that Snaith reveres, this trilogy of recordings comprises conversations with Chaco Kato,

Sally Smart and Maree Clarke. Extending her concept further, Snaith has produced a series of modular ceramic wall works as a responsive gesture. Created in homage, this body of work functions as a unique document of trans- generational feminisms, revealing the artistic and political concerns of leading Australian female artists through intimate conversations.

Starlie Geikie’s practice deconstructs the boundaries between formalism and craft. Spanning a range of media, her works rethink traditional craft-based processes, including fabric dyeing and quilting, through an expanded sculptural practice. Geikie mines a rich archive of historical references and her work is informed by a number of female modernists and iconic craft practitioners, such as Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889–1943) and Sonia Delaunay (1885–1979), as well as utopian architectures.

6. The #MeToo movement spread virally after American actress Alyssa Milano tweeted the phrase at around noon on 15 October 2017 to draw attention to sexual assault and harassment in the workplace. It had been used 200,000 times by the end of the day. On Facebook, the hashtag was used by more than 4.7 million people in 12 million posts during the first 24 hours. The global movement had repercussions across a number of sectors globally, with many perpetrators of sexual assault and harassment being held to account.

Translated through post-minimalist strategies, Geikie’s installation is constructed from a series of component craft forms that function in visual dialogue. Hand-dyed calico patchwork fragments are positioned in conversation with knotted cord and two-dimensional wall works. A banner without words leans nonchalantly against the wall, pregnant with interpretive possibilities. Framed raw edge quilted works, such as We were river people 2012–13 and Oubliette 2012–13, blur the dichotomy between art and craft.

Working across painting and ceramics, Karen Black explores politically charged themes around war and female-driven narratives across time and place. For Black, the surface of the clay body is equivalent to the canvas ground of her paintings. Coloured slip is applied in gestural brushstrokes and daubs of paint are allowed to weep and cascade downwards. However, these layered surfaces are not decorative. They express narratives about female experience and feminist critique around the control and exchange of women’s bodies as chattels.

Temporary arrangement – yellow in 3 parts 2017 lifts its form from a 3–4th century AD Roman perfume bottle that Black has mathematically up-scaled from the original. Black considers the bottle an enduring form that is inherently political, having survived centuries of conflict.

This large-scale, predominantly yellow vessel with a fluted top depicts a graphic scene of a female refugee giving birth in a war zone. The length of grey-blonde human hair resembles a tassel that might be attached to a perfume atomiser. Severed and resting on a plinth, it could alternatively be read as some kind of trophy, a sinister souvenir from a sexual conquest or a relic from a battle zone.7

These sculptures function as memorials of survival, reflecting the endurance of Syrian refugees with whom Black worked in Reyhanli, the Turkish border town for the crossing from Aleppo. Through her ceramics, she recalls the social displacement experienced by millions of women within the ongoing global refugee crisis.

The above artists discussed as part of Craftivism. Dissident Objects and Subversive Forms interrogate the histories of gender and representation and create new forms of identification and identity through craft practices, including knitting, quilting, ceramics and collage. While Paul Yore reflects on the Australian cultural landscape, his work concurrently reveals a language of queer expressivity, seen also in the work of Deborah Kelly and Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran, who co-opt art and cultural histories as a means to refocus the lens on LGBTIQ+ representation. Karen Black’s ceramic sculptures act as symbols of endurance and survival, monuments to the idea of a unified female experience that is connected across borders. The materiality and subjects of Kate Just’s knitted imagery pay homage to feminist activism, while the works of Starlie Geikie and Tai Snaith similarly draw on female-centred narratives to rethink craft traditions and the position of craft within a contemporary art context.

7. Anna Briers, ‘Beyond Materiality: Histories Re-thought and Re-imagined’, in 2017 Sidney Myer Fund Australian Ceramic Award (ex. cat.), Shepparton Art Museum, 2017, p. 15.