Purukuparli story—

Pedro Wonaeamirri

Ngawulayapunjami japumpunuma punjami, Ngawulayapunjami japumpunuma punjami, Ngawulayapunjami japumpunuma, punjami, pumpi, wiya . . . Ngawulayapunjami japumpunuma punjami, Ngawulayapunjami japumpunuma punjami, Ngawulayapunjami japumpunuma punjami, pumpi, wiya . . . Ngawulayapunjami japumpunuma, punjami, pumpi, wiya

Old Tiwi songline. Purukuparli calling out telling the world: ‘now my son is dead, now we all have to follow him’.

A long time ago before there were many people on earth, there was a place called Yimpinari, on the eastern side of Melville Island. On this place there lived a small family: Purukuparli, Waiyai and Jinani. Purukuparli’s brother Japarra was staying not far away on the other side of a creek. At that time, they were the only people on earth.

Purukuparli was a very important man to the Tiwi. He is the idea of a great man, like a cultural leader, strong and heroic. He introduced the Pukumani ceremony to all the people that have their home on the Tiwi Islands, north of Darwin. This story is of a time in the past that we call Parlingarri (olden times), before death came to the islands and when the differences between human, animal and Country were less clear. It was long time ago, in fact, Purukuparli’s mother Muntankala who had brought light to the earth, she was the first to come up from the underworld with three children in a tunga (bark bag) on her back. We believe that as she crawled in the dark, she created the ocean straight between the two Tiwi islands with her body and then left her son Purukuparli and his two sisters on the dry sand.

Some years later, Purukuparli, Waiyai and their baby Jinani lived in a bush camp at the place called Yimpinari. One morning Waiyai said to Purukuparli, ‘I’m going out to get some yinkiti [food] and kukuni [water].’

She put her son down under a shady tree and then went out in the bush alone searching for that yinkiti. While she was away, she saw Japarra and instead of looking for food she went off to make love with him. Purukuparli who was still at the bush camp then went out for a walk. While he was walking around, he found his son dead under the tree where Waiyai had left him earlier. The wanarringa (sun) had moved in the sky and the shade of the tree was gone, leaving the baby exposed. He then started calling out to Waiyai, but she did not reply back to his calls and Purukuparli knew something was really wrong.1

Purukuparli picked up his baby son and went looking for Waiyai, all the time calling out. Before he could find Waiyai, it was Japarra who answered his calls. ‘What’s wrong?’ he said.

‘My son is dead,’ Purukuparli said. ‘My son is dead and now we will all die. From now and forever.’

Japarra really wanted to help his brother and replied, ‘I will take our son for three days and bring him back to life.’

Purukuparli said back to him, ‘No, our son is dead.’2

He put his son back down under that tree and picked up his spear in anger and said, ‘miyuwarrimi’, which means ‘me and you fight’.

Japarra then picked up his own spear. Purukuparli threw his spear and first missed his brother. He then picked up a fighting stick and hit the side of Japarra’s forehead. Japarra did not fight back, but when Purukuparli threw that fighting stick and hit him, Japarra said: ‘waya juwa’ (finish) and put his fighting sticks down. He started singing to himself. Purukuparli stopped the fight and everything else was quiet. As Japarra was singing and dancing, he started flying up off the ground. He was a powerful man too, that moon man. He kept flying up far into the sky that covers the earth and that is where we see him today. Whenever there is a full moon we can still see the mark on his face where he got hit by his brother – the right side of his forehead.

The next morning where Purukuparli was staying at that bush camp near the beach, a pelican and egret came to meet him. Before these characters were birds, they were human. This was Parlingarri, a time when humans could change into animals. The birds had heard that Purukuparli was going to hold a ceremony for his son’s death. From Parlingarri to today, birds are still considered messengers for the Tiwi people; for my tribe the white cockatoo is a messenger for us.

After hearing about the ceremony, the pelican and egret offered feathers from their own bodies to make ceremonial ornaments such as pamajini (armband), pimirtiki (headpiece), tokwayinga (feather ball) and impuja (false feather beard). Purukuparli made these ornaments to disguise himself from the spirit of his son. He had a big ceremony for Jinani – it was to become the first Pukumani ceremony. The whole time Waiyai was upset, crying and swearing to herself about what she had done. She felt very guilty.

As Purukuparli was dancing and singing in the ceremony, he was moving down the beach toward the sea.

‘Ngawulayampanjami punjamimi jumpunipunuma punjanimi’ – ‘We all have to follow,’ he was singing.

He picked his son up and as he walked, he stomped a beat into the ground with his feet and was singing to himself. This was to let the world know that everyone to come after this ceremony were to follow him.

‘You will all have to die and follow my son,’ he sang.

As he carried his son into the water it got deeper and deeper and the winga (saltwater) came up until they both disappeared under the surface – that was it.

Waiyai continued to cry and mourn for her deceased son. She was ashamed of herself and what she had done. Like today, partners can become ashamed. This was a lesson for that lady, that whole family and for all Tiwi. Then ashamed of herself, as she continued to cry, she transformed into the curlew bird. Like the way the lessons of this story follow our people, the curlew continues to cry out at night. We hear her when it is dark at night-time. Calling out and searching for her dead son. Looking around for him under the light of Japarra – the moon.

This story of Purukuparli, his wife and son, is important to Tiwi life and culture. It teaches lessons about life and is also the beginning of our ceremonial culture. Since the time when Purukuparli danced his dead son into the sea at Yimpinari, the Tiwi people have come together for the Pukumani ceremony – to sing, dance and farewell the spirit of our family so they can be at rest back on Country. Pukumani ceremony is a grieving ceremony, but it is also a celebration of life. Every dance has a song. The song and dance are how you connect to the land and the spirit of the deceased person. To let go and say goodbye, see you next time on your Country.

Compiled by Will Heathcote with Pedro Wonaeamirri at Jilamara Arts and Crafts Association, Milikapiti.

Resource for spelling and translation:

Jennifer R Lee. Ngawurranungururumagi Nginingawila Ngapangiraga: Tiwi English Dictionary. Bathurst Island, NT: Nguiu Nginingawila Literature Production, 1993.

Pedro Wonaeamirri is a senior Tiwi cultural leader with significant knowledge of the ‘hard’ Tiwi language and the songs and dance important in Tiwi culture. Wonaeamirri grew up in Pirlangimpi (Pularumpi) on Melville Island, where he was born in 1974. He was educated in Darwin and returned to the Tiwi Islands in 1989, moving to Milikapiti in the same year that Jilamara Arts and Crafts was incorporated, where he currently practices as a senior artist.

Puruntatameri

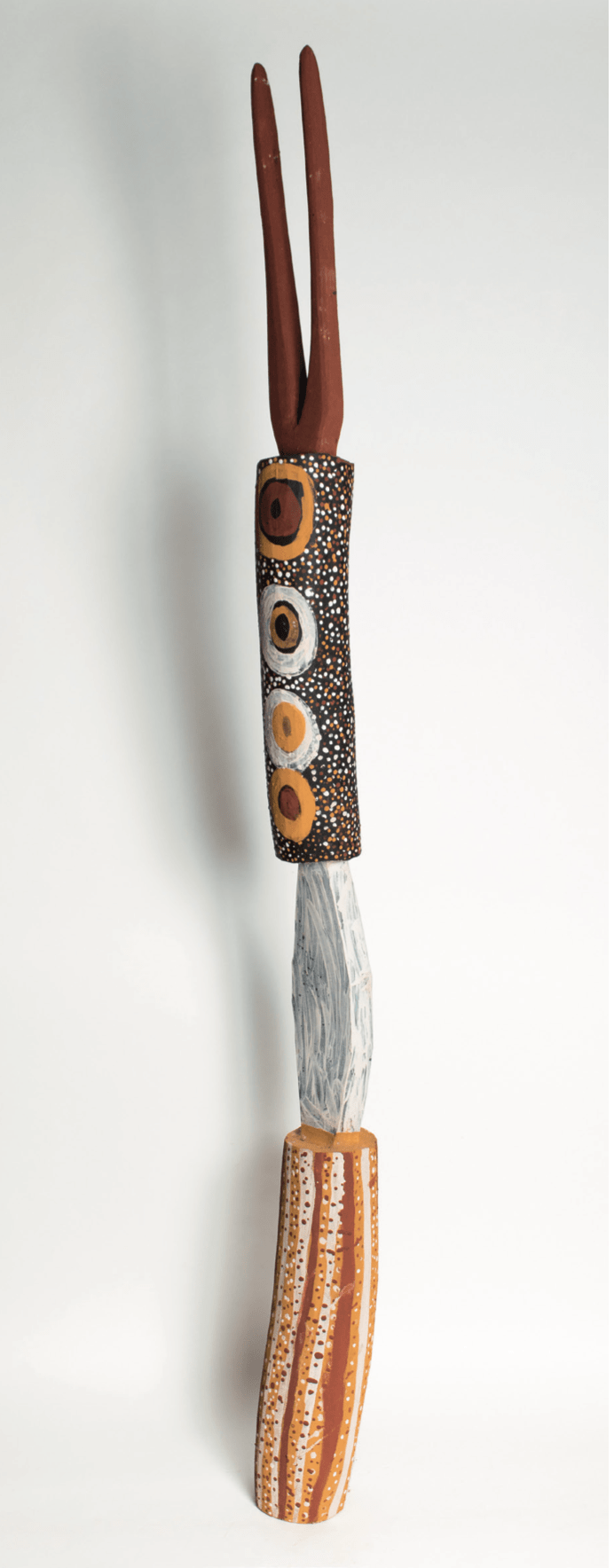

Tutini (Pukumani pole) 2020

Puruntatameri

Tutini (Pukumani pole) 2020

Purukuparli 2020

Waiyai 2020

Purukuparli 2020

Tutini (Pukumani pole) 2019

Waiyai (detail) 2020

1. Today whenever we go out hunting, we call out to see if everything is okay. Sometimes when you do not hear back you know that there is something wrong. We still call out on Country. Many parts of this story make up who we are as Tiwi people today.

2. In Tiwi way, because Purukuparli and Japarra are brothers they call Jinani ‘our son’. The boy connects with Japarra through the father’s side, therefore Japarra calls Jinani ‘son’ and Janini calls Japarra ‘father’. When siblings of the same gender have children on the Tiwi Islands they are also their children and they call their aunties and uncles ‘mum’ and ‘dad’. This is the Tiwi way.