I Hope: Instagram and The Political Stitch—

Rebecca Coates

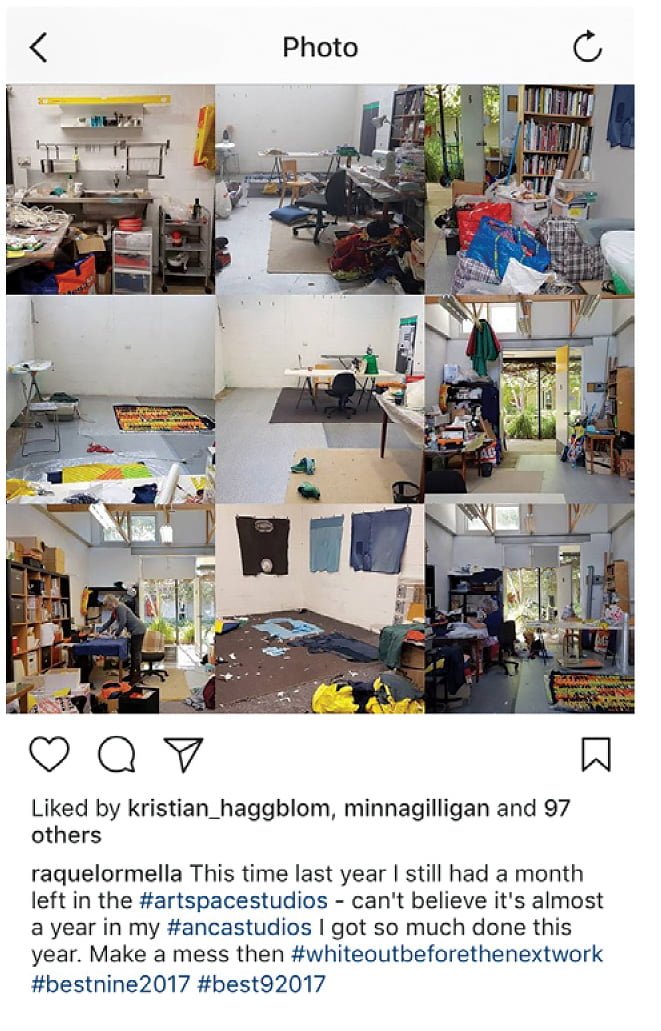

As Raquel Ormella started to prepare for her major survey show at Shepparton Art Museum, small intimate embroideries began to appear on the artist’s social media platform of preference, Instagram. These images of new embroideries and skeins of coloured threads for embroidery palettes were accompanied by a series of biographical commentaries and hashtags about hoarding and unfinished objects (or UFO’s as they are called by some people I know with similar habits). I was in Shepparton, Ormella in New South Wales; but Instagram shared the intimate and the professional with instantaneous visuals.

For an artist working in the traditional materials of fabric and thread, how did 21st-century Instagram modify and mediate the artist’s voice?

Finding a social media platform that suits is one of today’s First World challenges. Each of us, in both our professional and personal lives, has a favoured online platform. Many in the policy and political worlds have a penchant for Twitter, the preferred medium of current US President #trump #fakenews. It seems to lend itself to the narky comment, the policy rant and occasional links to more serious analysis. I missed the first Facebook wave, and now leave that to younger and older generations, who message in their sleep and share holiday pics and family idylls with envious others.

Instagram seems to be designed for those who work with images. A pithy hashtag or smart one-liner is usually all that’s needed to complete the story a picture tells. Numerous artists and arts professionals have leapt onto the medium. Many have merged personal and public personae, with varying degrees of privacy or veracity. Raquel Ormella and other artist colleagues in Australia and overseas have all made the medium their own. Nell has over 7K followers, Glenn Barkley 10K and Ben Quilty over 32K, while artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries, London, and uber curator of our age, Hans Ulrich Obrist, has 215K. They don’t rival Beyoncé at 113M, but that’s another story. It makes the world seem smaller, our community more global and our idiosyncratic hobbies more rational as we link with a subset of like-minded others sharing interests in a particular visual meme, the experience carefully curated, not by human hands but by an ever more subtle software algorithm that reflects our desires back to us. For the artist and art professional, while the approach may look casual, the successful site is as carefully curated as any other big-ticket show. As much, if not more, rests on the follow, with an audience that is immediate and global in its reach.

There are, of course, pitfalls for those not born with a screen or device in their hands. At a recent international conference, one of my curator

friends described the current state of curating as #itscomplicated. So too can be social media: one well-known arts professional, though widely followed, is regularly criticised by artists for uploading images of artworks badly captured or with wonky edges. There’s a growth in Instagrammable artwork, which can appear so much better on the screen than in the flesh. A social media frenzy surrounded many of the artworks in the National Gallery of Victoria’s epic

NGV triennial 2018, is perhaps presented precisely to encourage such a reaction. And while artist and activist Ai Weiwei’s most recent giant inflatable, Law of the journey 2017, was billed as the show stopper of Mami Kataoka’s Biennale of Sydney 2018, millions had already seen images of the artwork in its previous presentation at the Prague National Gallery in 2017, circulated widely around the world on social media.

Ormella uses Instagram less to create a global brand or identity-driven following, than to create and connect with more localised groups. An avid birdwatcher, or ‘twitcher’ as they are affectionately known, her connection with local ornithology groups in cities and regions wherever she travels enables her to tread lightly and at a slower pace. The self-portrait she has selected for her Instagram profile reveals this activity, though she herself is partially obscured by a great big pair of binoculars.

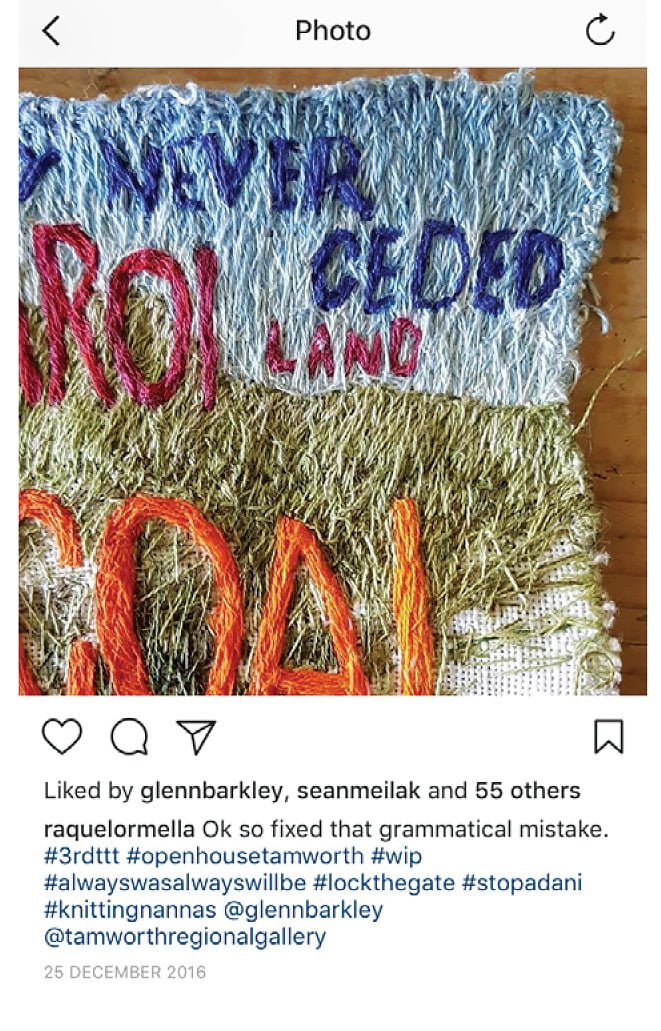

Ormella has long been interested in how communities work, actively participating in grassroots organisations. Often, there is a social or political agenda, with a strongly personal connection, though Ormella has in the past been cautious about these works only1 being read through this prism.1 Wild rivers: Cairns, Brisbane, Sydney 2008, four whiteboards covered in permanent marker drawings, and their associated works on paper, as well as banner works included in this exhibition, refer to political activism and the desire to find a personal voice within it.2 The text in many of Ormella’s banner works alludes to biographical aspects of the artist’s own life as well as national events and political utterances. The very title of this exhibition, I hope you get this, reveals Ormella’s hope that her own artist’s voice is heard in the exhibition and provokes her audience to action.

Ormella’s Instagram feed features fabric stashes, embroidery threads, unfinished objects, Pantone colour swatches and the slow art of lost crafts, as well as a small number of artworks by others she particularly likes. It could be seen as part of a massive global return to the handmade, where workshops, practical demonstrations and other offerings of TAFEs, universities, Adult Education providers and many others sell out as rapidly as they are offered.3 It’s the online update to the ‘stitch’n’bitch’ sessions of old – even when these were advertised online, they still required people to catch up in person for

a regular session of gossip and keeping hands active. Ormella’s version has all of the same community sentiment and connectedness, but like many other activities in our online world, it can occur at our own leisure and location, as part of our ‘downtime’, and without the hassle of getting out of our slippers.

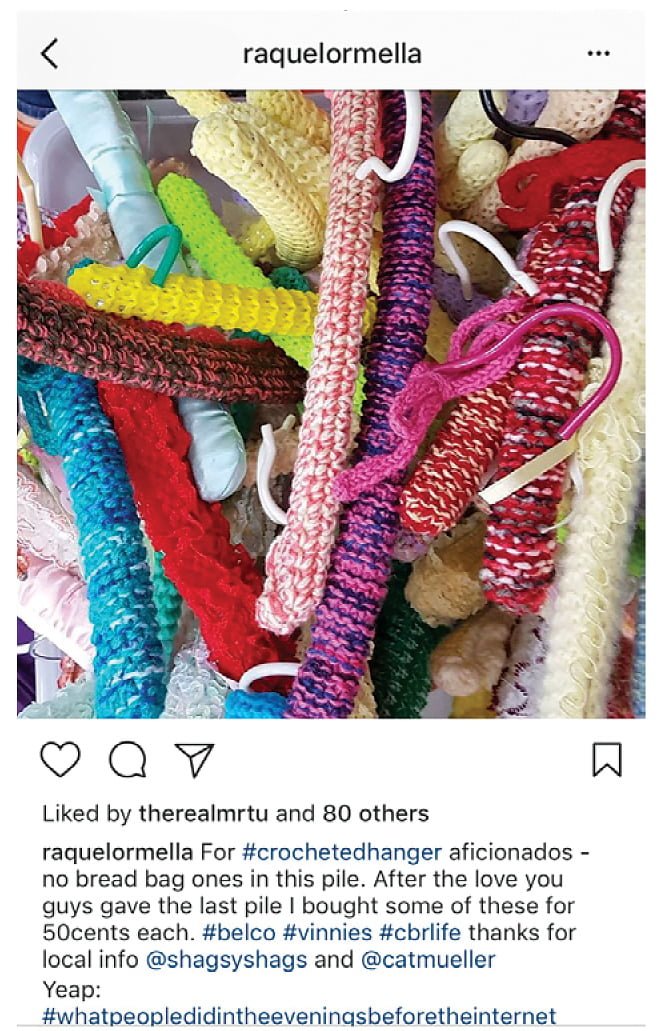

Ormella’s sentiments clearly resonate with her growing number of followers. Alongside her own

small embroideries she posts stashes of hoarded and leftover fabrics and finds from church fetes, car boot sales and opportunity shops, usually embroidery thread and textiles, but also extending to the crocheted coathanger, at 50c a throw. The St John’s church fete was clearly a particularly rewarding day. Visits to her parents’ house, or the move to a new house and studio, reveal forgotten treasures unearthed from

the attic. Ormella muses on her habits with hashtags

– #tryingtostophoarding #notreallyreallysucceeding #theonewhodieswiththemostfabricwins #hoardersunite #thestash.

One attic find was a doll’s house made by her father and the box of #dollshousefurniture that went with it. Ormella notes, ‘This time last year I let that go

1. See, for example, Lizzie Muller, ‘An interview with Raquel Ormella’, in Raquel Ormella: she went that way, exh cat, ed Reuben Keehan, Artspace Visual Arts Centre, Sydney, 2010, p 32.

2. See Reuben Keehan’s essay for a discussion of these works, p. 20–21.

3. See, for example, Alexander Langlands, Craeft: how traditional crafts are about more than just making, Faber and Faber, London, 2017, where the current meaning and revival of craft seems to have little to do with the act of making.

into the world. And thanks to Insta it found a new home … It is now with Nicole Barak’s niece being loved and that is [where] the furniture is going too …1970s.’ Ormella confesses on a visit to Shepparton that the furniture had been harder to part with, a memento as it is of 1970s design and pure plastic colours.4 Subsequent posts of the furniture reveal Ormella’s feminism, the influence of both parents on the development of her political views, and a wry humour. She writes, ‘Of course every girl in the #70s needed several kitchens – even when raised by a #feministmother’. The fridge was bright green – with a clarity of colour tone echoed by many of the greens Ormella has subsequently used in her fabric works. Pictures display the furniture doors opening, and the wear and tear of much love and use over the years. ‘You need a sink to be chained to afterall [sic] – amazing that the teatowel is still stapled to the rack after 40 years … All the furniture is different scales and come to think of it I really remember the furniture and the house but not the dolls … or the smallest ones I had would have been giants in the house #oldplasticcanbesoabject.’

A post on International Women’s Day 2018 features

a plastic iron in the same red, green and white plastic as other doll’s house furniture, photographed from various perspectives. Ormella writes that it was a Christmas gift from Santa when she was about four or five. ‘I am sure I am not the only one whose parents were contradictory and complicated. Giving thanks to them today for raising me a feminist.’ And to ‘all those art mothers who helped [me] think through / feminism’s complex history’.5 The final image is of the underside of the iron, where she draws attention to ‘check out the scar-face surface. This was a well used toy.’ The art/life/politics thing – #itscomplicated.

Ormella has long used fabrics and other textiles to create large sculptural paintings and wall works. For Ormella, whether stitched by hand or machine, her materials have the patina of their original purpose, such as the dark blue of KingGee workwear favoured by blue-collar workers, including her own father, or the high visibility reflective fabrics that the mining boom turned into airport-wear. There’s always two sides to

a story, however, and Ormella’s artwork is infused with the environmental and social effects of this economic activity: from the landscape damage of mining to

the social dislocation and family stress of a ‘fly-in, fly-out’ generation of workers on 20-day rosters.

Ormella’s choice to work in fabrics and thread, two traditionally female materials, has some roots in Rozsika Parker’s influential book The subversive stitch, 1984.6 For Ormella, it remains a seminal text and she cites it as playing a significant role in her rethinking of the gendered nature of art-making, materialities and labour. Parker notes that embroidery only became a purely female activity in the early modern world. Both men and women worked in the guilds and workshops of the Middle Ages. And needlework has always had class-based overtones: whether for goods produced for the rich, given the cost of the materials and hours of labour – however cheap; handwork for those who could afford the leisure time; or skills re- appropriated to create banners of solidarity early in the labour movement.

Republished in 2010, The subversive stitch now includes the work of leading contemporary artists Louise Bourgeois and Tracey Emin. In Parker’s updated introduction, she notes that if Bourgeois had made work in these media before 1985, extensive chapters

4. The artist notes that most has now been given away. Email with the artist, 11 April 2018.

5. Instagram quotes have been referenced as written by the artist, spelling and grammar intact to the original post.

6. Rozsika Parker, The subversive stitch: embroidery and the making of the feminine, IB Tauris, London, New York, 2010. Ormella also cites political theorist Jane Bennett’s book Vibrant matter: a political ecology of things, 2010, as central to her work, in which the author argues that a ‘vital materiality’ runs through and across bodies, both human and nonhuman.

would have been allocated to her art. According

to Parker, Bourgeois, who frequently employed embroidery and fabric in her work, perhaps did most to restore fabric and stitching ‘to their place within “high art”’.7 Bourgeois’ work in fabric refers back

to her childhood, her own family, female sexuality,

the unconscious, psychoanalysis and the body. Her parents ran an embroidery restoration business, and she famously never threw out a single piece of fabric or clothing. Ormella’s photographs of the 1970s plastic furniture from her doll’s house could easily be read as a rethinking of Bourgeois’ famous Femme maison series.

Tracey Emin has used embroidery and fabric differently, to expose the gap between imposed femininity and lived female sexuality. A product of 1990s Britain, her autobiographical sharing of her dirty sheets, sexual proclivities and sleeping partners was embroidered onto the inside of a camping tent. It took fabric, textiles, embroidery and tapestry into an altogether different contemporary realm.

A spate of recent exhibitions document this trend: from the inclusion of Sheila Hicks and Lee Ming Wei’s Mending project in recent editions of the Biennale of Sydney and the sheer number of textile-based works by both men and women in the 2017 Venice Biennale to institutional shows in 2018 such as Surface/depth: the decorative after Miriam Schapiro at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design (MAD).8 This exhibition has provided a timely rethink of the legacy and influence of great second-wave feminists such as Schapiro, Judy Chicago and others on a younger generation of artists.

Since The subversive stitch was first published in 1984, amidst the blare of second-wave feminism

and a celebration of all things CRAFT, contemporary art has evolved. The disparity between male and female wages in the arts may still be vast; so too

the number of men with major survey shows and with artworks acquired by leading art institutions.9 But on a positive note, the division between art and craft is breaking down. Artists now working in these materials extend the potential of traditional craft media, such as ceramics, tapestry, embroidery or even knitting, to become part of a contemporary dialogue. Like others, Ormella’s interest in these materials is in large part located within the ‘art world’ within which she works, which contrasts to the ‘craft world’ of amateur makers and the everyday. It is a similar appeal of making and materiality that we are seeing play out in the ceramics world across both spheres – that of the passionate creative and of the art world professional. Neither is better, but they are different. And each informs the other. Textiles and clay offer artists a sense of the potential for social inclusion, a delight in the material, an ability to harness the exotic and the gaudy within

a conceptual frame, and a sheer revelry in the notion that anything goes.

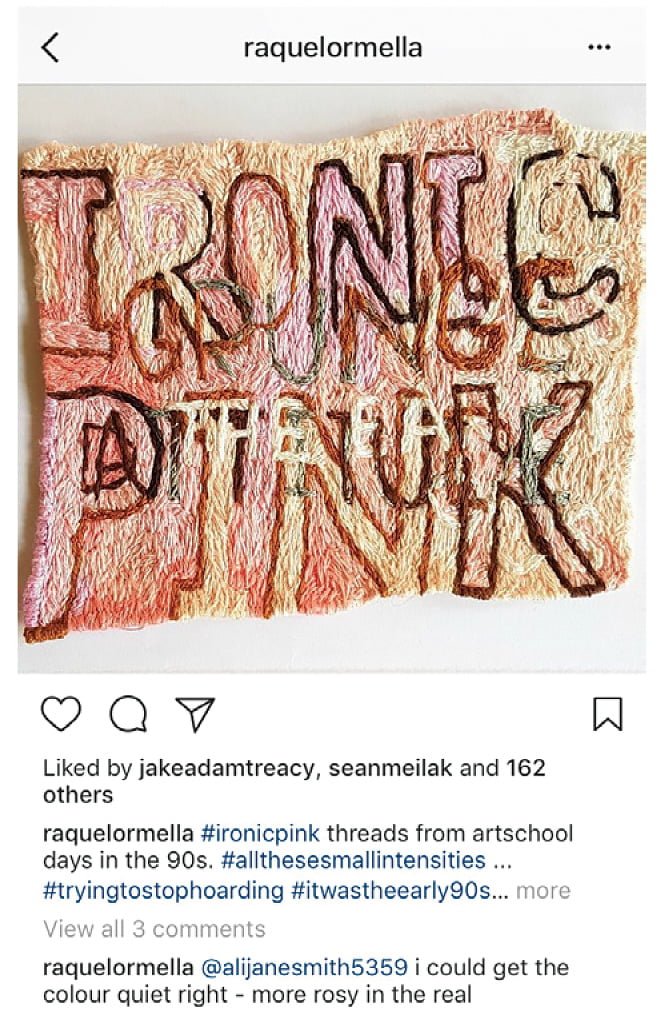

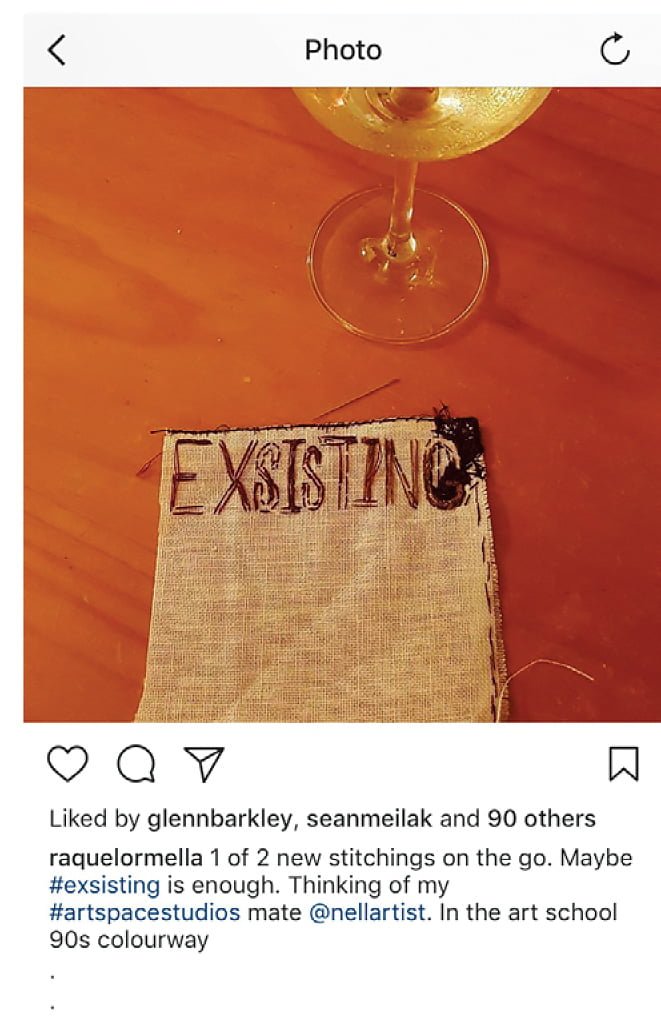

The series of small embroideries, All these small intensities 2017–18, that Ormella has presented for the first time at SAM are all deeply personal, as their titles intimate: I hope you get this, Feminist politics, All these small intensities, Contemporary embroidery, Drawing with thread, Grunge colour attitude ethics.

Ormella divides them into three distinct periods. The first relates to her childhood, when Ormella was keen on ‘craft projects’, picking up skills either by osmosis or from her mother. The second reflects her time at art school in the 1990s, when she used tapestry and embroidery stitching as a

7. Parker, introduction, p xviii.

8. See Glenn Barkley, ‘Open house’, in Open house: 3rd Tamworth textile triennial 2017, exh cat, Tamworth Regional Gallery, 2017; Alina Cohen, ‘How Miriam Schapiro’s feminist work transcended the line between art and craft’, Artsy, 29 March 2018, artsy.net/ article/artsy-editorial-miriam-schapiros-feminist-work-transcended- art-craft; accessed 1 April 2018.

9. See, for example, The Countess Report, 2016, thecountessreport. com.au; accessed 2 April 2018.

form of anti-painting. And the third corresponds to the 2000s when, as she notes, ‘I became a bit of a hoarder’.10 Nothing from the first period of childhood craft activities has seen the light of day, save the photographs of her doll’s house furniture from this period, now shared on Instagram.

GRUNGE COLOUR ATTITUDE ETHICS is made from coloured threads remaining from the art school 1990s, and uses what Ormella describes as a ‘dark and drab’ palette of browns, greys and some blue – the colour of her father’s work clothes. Alternating with these intimate-scaled objects presented front and verso

are photographs of original Coats & Clark embroidery skeins bought during this art school period.

Ormella does recall that the works for which she bought the thread in the 1990s were a series of

small paintings about her migration story and her relationship with her parents, which also included a stitched element. In an Instagram post, she describes her father’s story as ‘Barcelona, Germany, Peru, Australia. War – crisis – economic redistribution – work’. Commenting on this post online, art historian and academic Chris McAuliffe notes, ‘muted tones, muted men, hanging around in clusters on worksites or at the pub, doing their silent type thing’. In their own way, these works provide another chapter in Australia’s visual story of workers and the economy, alongside John Brack’s Collins St, 5p.m. 1955, with its faceless workers and last-drinks rush. One of Ormella’s tutors at the University of Western Sydney at this time was Australian artist Narelle Jubelin. Jubelin’s intensive research process, her sourcing of objects with complex histories and reinterpretation of these histories, often through petit point, in works such as Trade delivers people 1989–90, first shown in the Aperto section

of the Venice Biennale, were so influential in locating Australian artists firmly within an internationally relevant postcolonial, or postmodern, debate.

Ormella describes the third phase of her embroidery making and collecting as one of acquisition and hoarding. The 2000s were a peak period for collecting ‘stuff for art’, for ‘material inspiration’ and ‘for

heart break’. She presents on Instagram a recent embroidery made from threads acquired from this time. Presented as two images, the one above reads ‘PEAK LOSS’, the one below, ‘PEAK ACQUISITION’. The embroidery is a series of squares with diagonal stripes in alternate directions: green and purple, yellow and orange, pink and green, pink and orange, red and pink, with text over the top in light and dark blue in contrasting diagonal stripes.

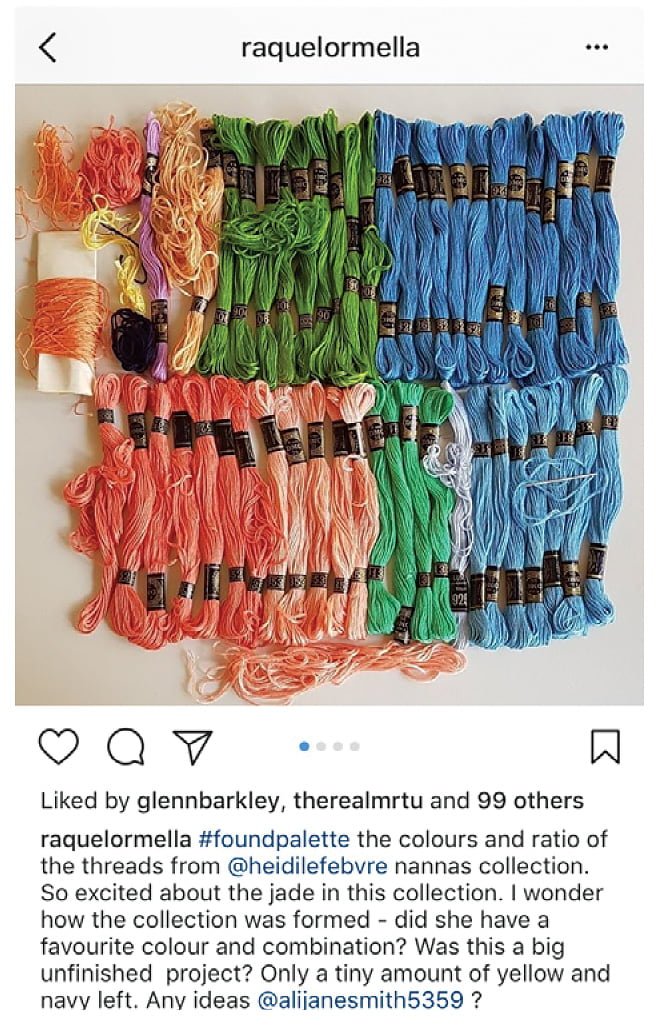

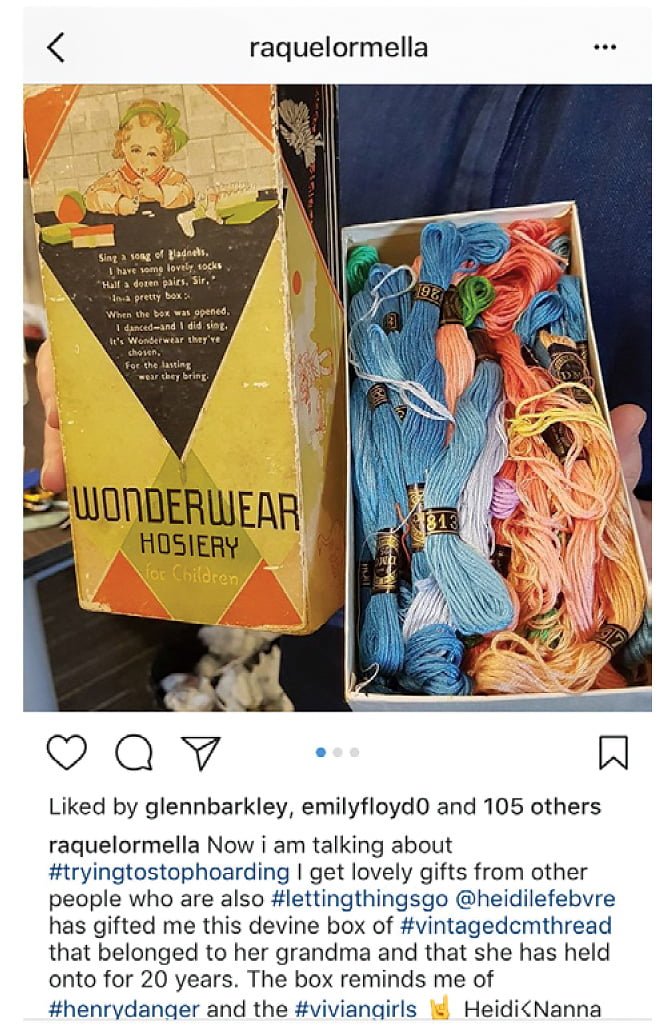

Each palette carries its own history. IRONIC PINK GRUNGE ATTITUDE is done in shades of cream,

pink and brown. It feels like a bastard child of

muted pastels from the 1990s, overlaid with a later colour palette that is a little more Pantone, a little more tasteful. The collision may reflect how people started giving Ormella their own precious things, once they knew she was reviewing and reworking

her own collections and hoards. A vintage collection of threads, complete with original cardboard box labelled Wonderwear Hosiery, attracts the hashtags #foundpalette and #lettingthingsgo. So precious

was its connection to the box’s original owner that the owner’s granddaughter held on to it for 20 years before handing it over to Ormella. Ormella notes, ‘DMC wrappers – a lot of 744. A pale yellow, of which there was only a small amount left.’ Ormella wonders how the collection was formed – did the grandmother have a favourite colour and combination? Was there

10. The artist in conversation with the author, 20 March 2018.

an unfinished project? Ormella notes that only tiny amounts of yellow and navy was left.

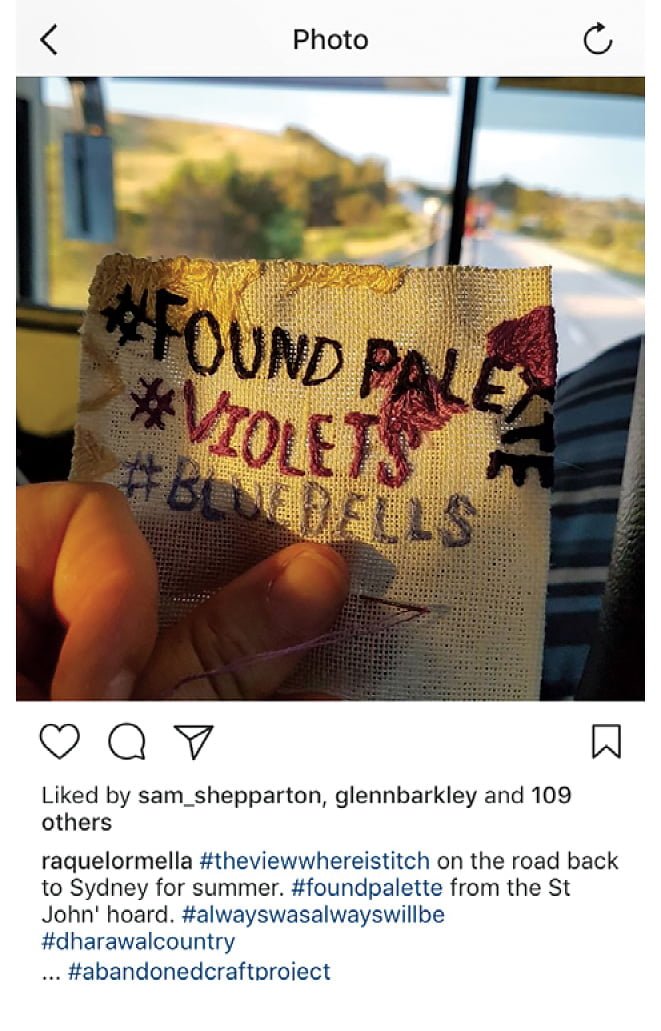

Her post of FOUND PALETTE, another work relating to this period, has the hashtags #violets #bluebells,

as social media and online community language makes its way into the actual embroideries. The picture shows a hand with needle and threads from the St John’s church fete hoard, all framed by a bus window.

COLOUR GLUTTON is another work made from thread purchased during the #peakacquisition

phase of Ormella’s life. The threads used in this work were sold as a group, and Ormella thought the palette so unusual that she wanted to work with it. She notes that there are ‘2 tones of 2 different chromatic greens; 2 tones of pink that are slightly different chroma; a dark purple; black and white’. In rethinking this found hoard, she also ‘added some extra colour and used cream instead of white. Only took 12 years.’

There’s a completely different history woven

into ENDLESS POTENTIAL, made from kimono threads acquired while Ormella was in Tokyo in 2010. Its aesthetic and materiality are emphasised by unfinished threads left dangling in clusters from the completed embroidery. The palette for this embroidery is largely white, with some faint pink text and blue markings coming through from underneath, not dissimilar to the exquisite kimono fabric the thread was originally conceived to weave. ONE INDECISION AFTER ANOTHER reflects

the difficulties of the process of making these embroideries and an insight into the artist’s process. Ormella notes that it was ‘Started on the summer holidays, unpicked several times, which is not what

I would normally do … taking out the blue grey this

time … cursed by the text … not sure if the indecision will read on the final piece.’ This work is made from all new threads, breaking with the old palette.

The recent series of embroideries presented in this exhibition draw together many of these threads. These works reflect on the histories of Ormella’s

life, her materials and the very process of making. Enjoying the process of stitching as relaxation as much as for its artistic content, Ormella frequently seems unwilling to let the works finish. And Instagram provides a public window into the history of making that was once the exclusive preserve of visitors to

a private studio. In Ormella’s Instagram feed, the artist’s hand is often present, as is her material. Skeins of thread are held between thumb and forefinger in front of the work in progress, which rests on the artist’s knee – often clothed in a similar colour or complementary pattern. This is colour swatching on steroids. The device of inclusion of

the artist’s hand is one Ormella has previously used, and locates the artist in the making, as well as in

our mediation of the subject. Now, however, this labour is often depicted in context: on holiday, on public transport while travelling, or simply in front

of a landscape scene beyond. It subverts the idea

of embroidery and tapestry worked somewhat mindlessly in the evening to keep idle hands busy. And yet, there is something enjoyable about this process of labour. And somehow, we seem to have come full circle. The artist now mines her own craftwork archive of treasures, selective memories and psychological compulsions, creating a new form of language that she shares via an online platform

as her works evolve. It’s an archly egalitarian gesture that intermingles art world and craft fanatics.