Contested Territories, Borders and Barriers—

Amelia Winata

In recent years, craft has frequently been aligned with the ‘nice’, the decorative, the apolitical. However, history tells us that countless artists working with craft have been deeply engaged with their socio-political environments and have often created in moments of absolute uncertainty, political unrest and shifting or unstable borders. Paul Yore, Jemima Wyman, Michelle Hamer and Penny Byrne build on a long tradition of craft as a site and generator of contestation. Bringing craft into the contemporary moment, these artists build on the loaded practices of their chosen mediums to consider current political world events involving territories, borders and barriers, such as the experience of asylum seekers, First Nations peoples and contentious border crossings in Europe and North America.

Looking back, we find countless examples of craft’s politicisation and social function, which have imbued its practice with meaning beyond the decorative and the aesthetic. Historical avant-gardes, so often bookended by wars (World War I 1914–18, World War II 1935–49, the Vietnam War 1955–75), were either directly or indirectly affected by the politics surrounding territories and borders. We might recall the Bauhaus (1919–1933) as a school that promoted the synthesis of the arts and taught a number of different crafts, including weaving and glassmaking, and a general preliminary course in various material studies – stone, wood, textiles and clay. Early on, the Bauhaus was scrutinised by the rising Nazis as representing ‘Cultural Bolshevism’ and in 1933 the school was officially closed due to pressure from the Nazis.1 In this sense, craft and the community created around it were seen as threats to Hitler’s regime of suppression and cultural homogenisation. Of course, the rise of Nazism

forced many to emigrate (indeed, many of the Bauhauslers were Jewish) and, in this sense, the notion of craft as political and the contestation of territory met. Josef and Anni Albers immigrated to the United States, where they taught at the Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Closer to home, Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack – a graduate in lithography from the Bauhaus – immigrated to Australia, where he taught art at Geelong Grammar after having been detained in an internment camp for nearly two years upon arrival.

Any artistic work or movement that operates in or as a reaction to society invariably has a social function that operates within the aesthetic. The present rise of right-wing global politics, including Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, has meant that artists are reassessing ways of expressing resistance and protest. In Chicago, Aram Han Sifuentes established the Protest Banner Lending Library after the 2016 US election. The library lends people banners to use

1. Karen Koehler, ‘Bauhaus/No Bauhaus: Small Worlds and New Visions’, The Small Utopia Ars Multiplicata, ed. Cermano Celant, Progetto Prada Arte, Milan, 2012.

at the ever-increasing number of demonstrations that are occurring since Trump came to power. The banners are made of fabric and are often elaborate, bright visual representations of the voices of everyday citizens, representing people’s anger across a range of contested issues in the Trump agenda. The artist also offers banner- making workshops where people can gather to learn how to sew banners while mobilising in creative resistance against the oppression of Trump’s government. This demonstrates the way in which craft-making techniques can be constantly renewed to work as vehicles for social change.

Yore, Wyman, Hamer and Byrne’s work co-opts traditional craft mediums as starting points to discuss politically oriented, contemporary subject matter. All but Byrne, have employed digital imagery in the creation of their pieces, combining the digital and the analogue to produce works that are anchored in tradition while commenting on our technologically advanced but socially disconnected world.

Jemima Wyman engages with historical examples of avant-garde craft to produce her own politically saturated designs. Propaganda patchwork 2016 and Propaganda textiles 2016–17 are the results of Wyman’s interest in contemporary protests and their connection to collective forms of action. Wyman’s textile designs stem from her study of Soviet textiles from the 1920s and 1930s. Soviet authorities hoped these textiles would shape the ideal Soviet citizen – a citizen that conformed to the ideal of a modernist utopia. These textiles idealised the new Soviet Union as an agrarian and industrial haven – which was far from the actual reality. Bright and repetitive, they offered a simple message of (false) hope to citizens of all literacy levels. Wyman’s textiles, on the other hand, borrow from the distinctive aesthetics of ‘collective skins’ worn by masked protesters depicted in the images she has been collecting from the internet for a decade.

If the Soviet authorities were hoping to design a utopia with their distinctive textiles, then Wyman’s textiles offer a visual representation of contemporary politics as decentralised and increasingly democratised by modern communications technology. This is the binding logic behind the swatch book as a token of ‘collectivism’, not to mention that protests are, almost inherently, group acts. However, the fundamental difference between Wyman’s fabrics and the Soviet textiles that inspired them is that the Soviet textiles were the result of a centralised form of government under the guise of ‘collectivism’ while the former are, indeed, a form of collective action. This is ironic given that the word ‘collectivism’ is typically synonymous with the Russian Revolution and Marxism, but is actually a term more befitting of the current-day protest movements depicted by Wyman.

Penny Byrne’s #EuropaEuropa 2015 is an ironic reflection upon the European refugee crises, issues from which can be transplanted directly to the Australian context. Byrne’s work is composed of a collection of vintage blue and white figurines arranged on a large serving platter. She has then added small pieces of orange epoxy putty to each figurine to represent life vests, an emotive visual trope of refugee narratives.

The blue and white porcelain that Byrne uses is layered with meaning. Produced in Taiwan in the middle of the 20th century and exported to Australia as household decorations, these figurines are based on Meissen porcelain – a luxury brand of 18th century German porcelain that idealised peasant life and was sold to the wealthy as table decorations. The figurines suggest a romanticisation of Europe by refugees which may not be representative of the modern- day reality of a Europe that is experiencing a rise in xenophobia and anti-immigration sentiment. These reproductions have in recent years been discarded en masse, often inherited but viewed as worthless pieces of kitsch.

Any artistic work or movement that operates in or as a reaction to society invariably has a social function that operates within the aesthetic. The present rise of right-wing global politics, including Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, has meant that artists are reassessing ways of expressing resistance and protest.

The parallel created between these objects as throwaway items and the sad reality of humans as disposable is not lost. Byrne’s treatment of the subject, by way of her chosen medium, is light-hearted. The miniaturised figures in #EuropaEuropa are viewed from above. This is a conscious tactic on the part of Byrne, who manipulates our perspective to mimic photographs of refugee boats taken by drones from high above, dwarfing the human lives who are identified by way of their orange life vests.

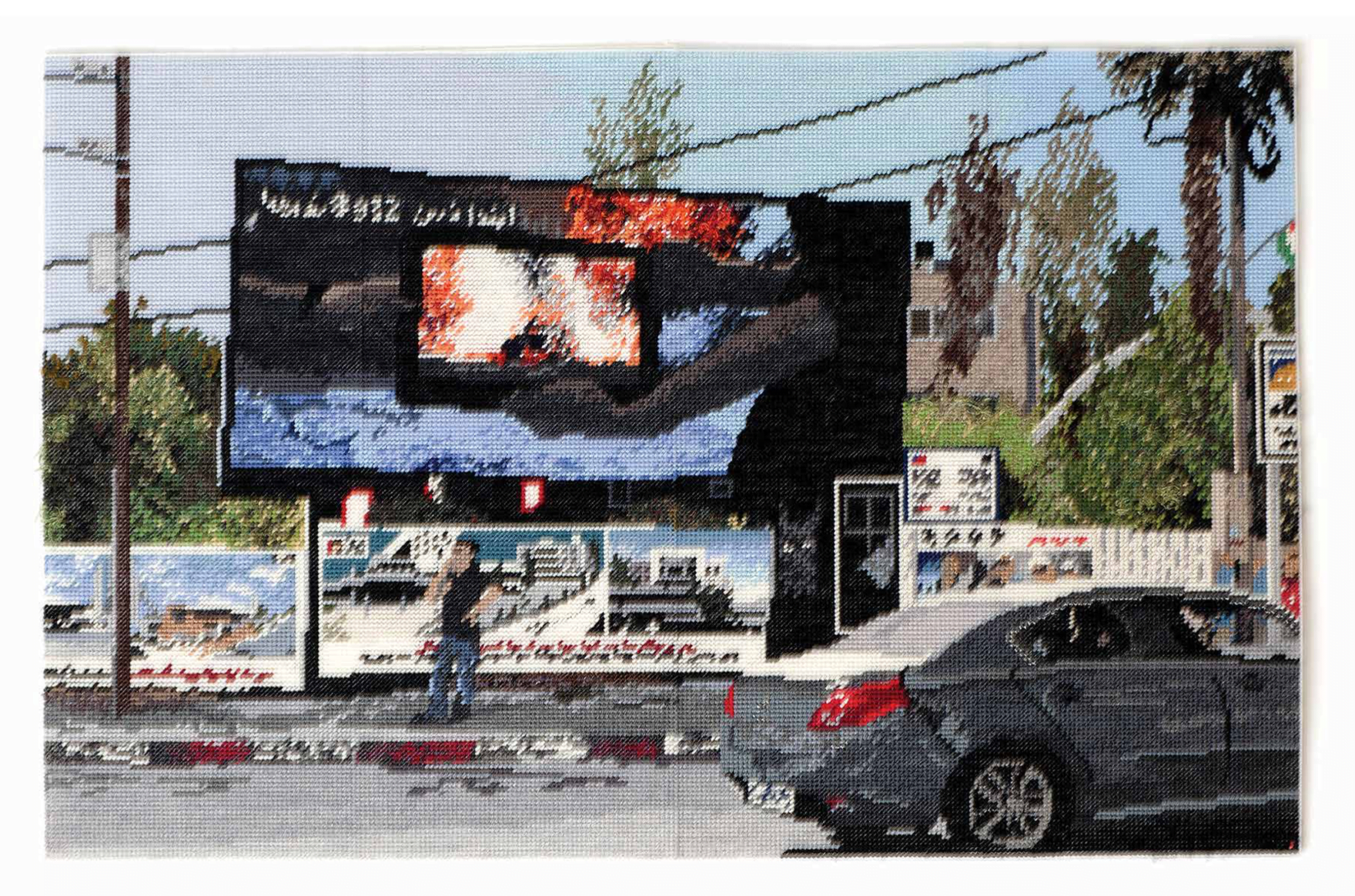

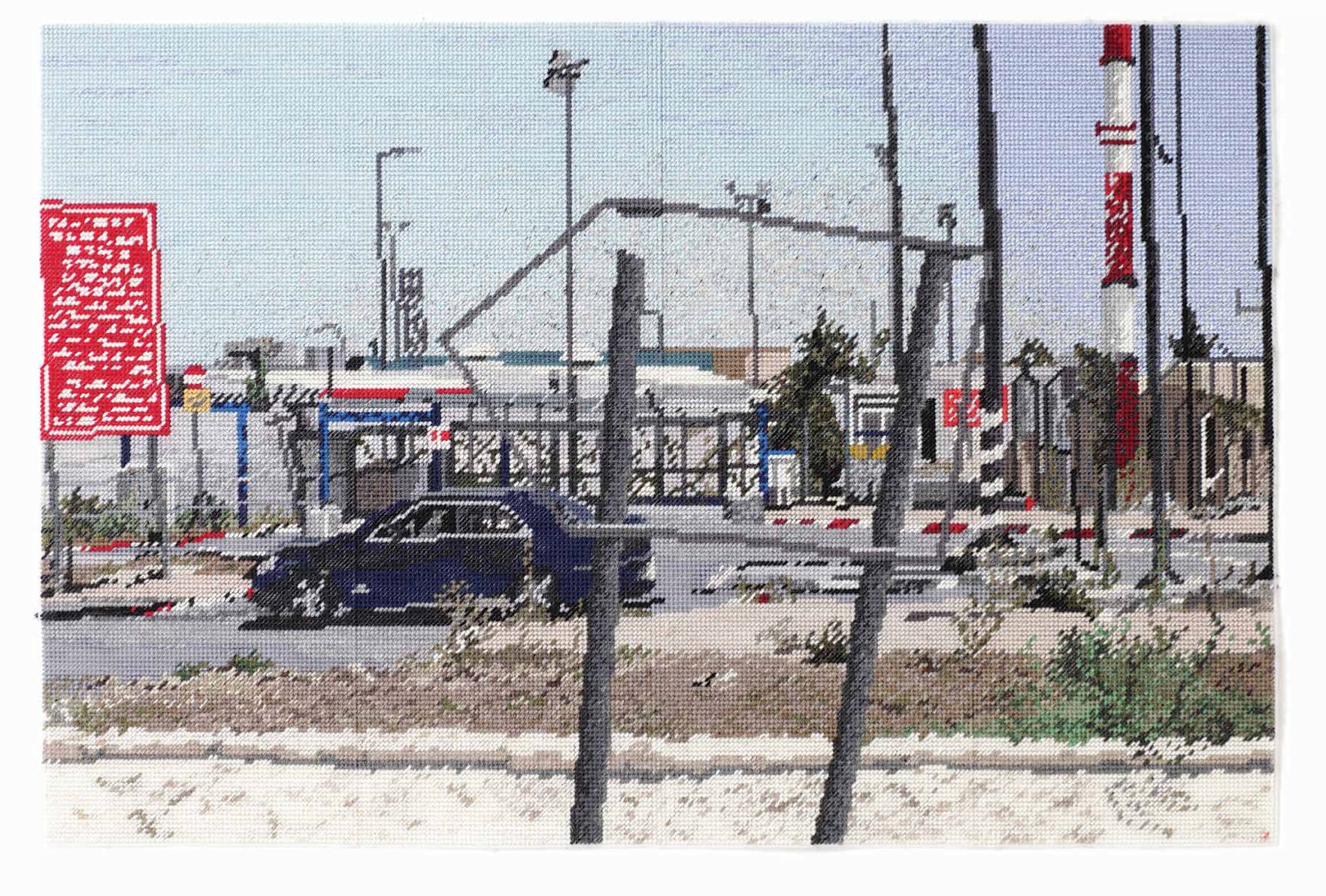

Michelle Hamer’s three hand-stitchings On the Road to Nowhere 2017, Imploding Explosions 2017 and Full. Stop. 2017 confront borders directly. In 2015, Hamer travelled to two of the world’s most contested borders – Mexico/ USA and Palestine/Israel. The resulting pieces reveal the way in which common visual languages operate across cultures and continents. Even without knowledge of the particulars of the scenes, the viewer can identify them as highway border stations, indicated by the presence of cars and remote infrastructure. The signage present in the works demonstrates the commonality of the issues surrounding contested borders in an increasingly globalised but divided world.

The stitching of each work can be understood as the pixellation of photographs, as Hamer says, ‘a stitch and a pixel are really the same thing’.2 The hand-stitching has a somewhat surreal quality to it, mimicking photography but without photorealism. The detached mood that Hamer’s hand-stitchings create mirrors the confounding political systems that these two borders embody, wherein we understand the situation’s reality but find the circumstances

surreal. A certain reversal occurs in Hamer’s work, that can be attributed to the translation of the digital to the analogue and the subsequent slowing down of time. In Imploding Explosions, a person on the Palestinian border chatting nonchalantly on the phone is oblivious to the dreamlike background of an advertisement featuring an explosion. Hamer recalls the sense of confusion that her experience at these borders elicited. While border zones are imagined as sites of tension and conflict, Hamer found that the reality was surreally unexceptional, noting that the images of horror created by the media might lend themselves to increased hysteria in conversations surrounding borders and state security.

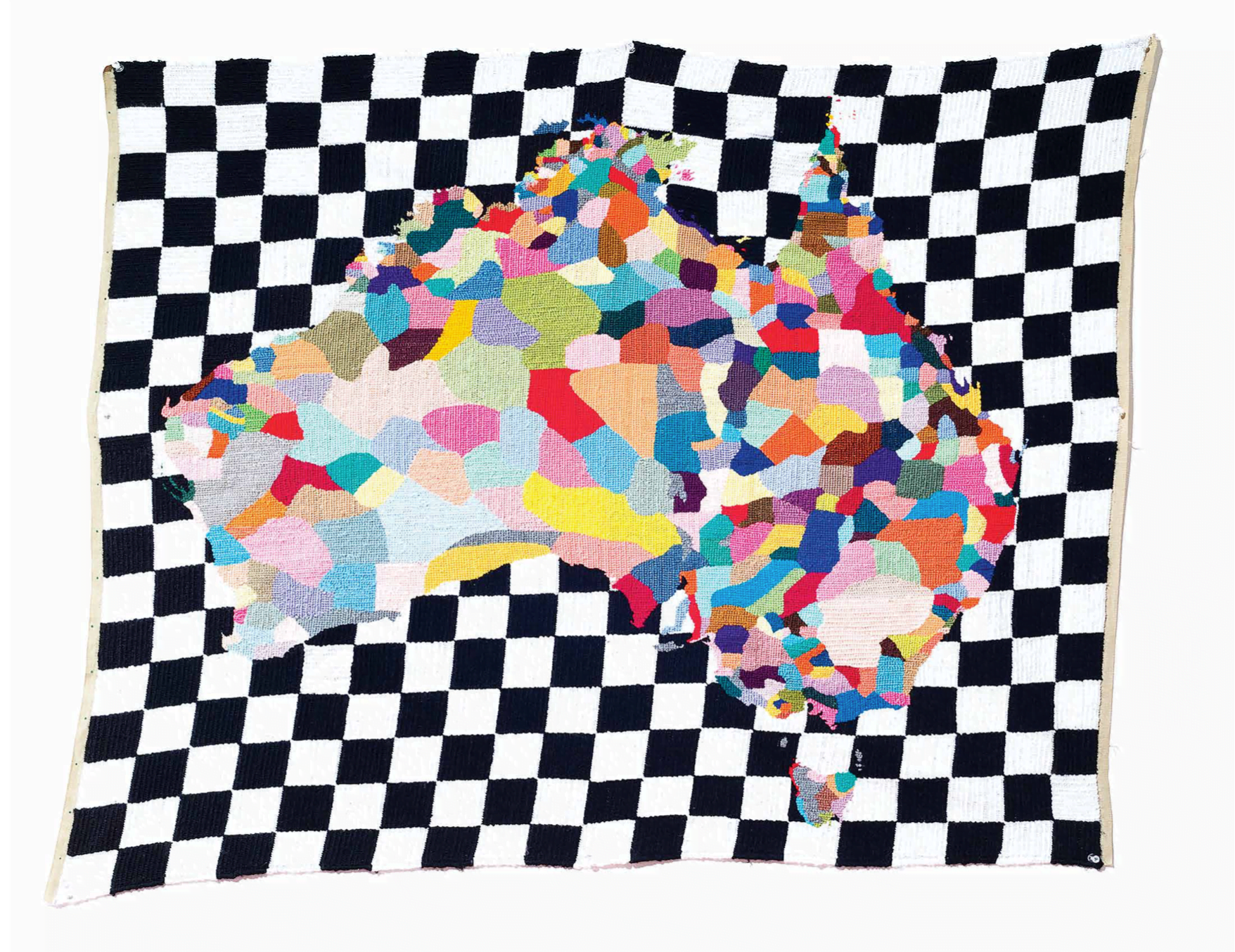

Paul Yore’s wool needlepoint Map 2012 is based on a map of Aboriginal language groups developed by European settlers. Highly problematic, it demonstrates the Western settler desire for compartmentalisation and easy categorisation. Yore says of the work,

Maps are inherently ideological through their intensive reductionism. The meaning embedded in the work is unstable, because it draws on the epistemic tension that exists in the process of attempting to “know” something: a place, a time, a feeling.3

The black-and-white grid that Yore’s map sits on top of speaks to this desire to know something. The grid is a standard structure used to produce empirical information, such as a map, while the notion of mapping Aboriginal language groups is obviously problematic insofar as mapping demands strict delineations of space.

2. Conversation with Michelle Hamer, July 2018.

3. Correspondence with Paul Yore, July 2018.

This work emphasises the deeply problematic logic of a European narrative applied to First Nations peoples and their identities. The concept is further compounded by Yore’s choice of needlepoint, a craft form long associated with Western cultures that has historically been systematically deployed as a symbol of power – professional embroiderers were often employed by wealthy families and courts to create needlepoint designs. Map exposes the ongoing domination of Aboriginal identity and culture in Australia by settlers, even in this so- called ‘postcolonial’ moment.

Our daily interaction with the media has oversaturated our senses with endless images of humanity’s violence and intolerance against our own kind. Byrne, Hamer and Yore harness traditions of slow handmade artistic forms that mediate the horror of such images, while Wyman employs visions of protest and resistance. Each artist grounds their consideration of the contemporary moment as part of a longer historical arc, as opposed to it being a discrete period cut off from the past. This is demonstrated by the artists’ deliberate use of their respective craft techniques that, having survived sometimes centuries of tumultuous histories, frame our discussion of the politics of human movement. The politics of border zones and the contested nature of land and territories are ongoing global concerns that span time.