Bäpurru—

Yinimala Gumana in conversation with Kade McDonald

Yinimala Gumana When someone has passed away, family or relatives participate in Yolŋu ceremonial way, the deceased person goes back to where they come from or where they are coming from and that’s why Yolŋu, every family or relative goes and participates in ceremony.

Kade McDonald So when you say ‘where they come from’ do you mean their ceremonial place?

YG Yes ceremonial place, like from every significant place where they have promised land.

KM When you are talking about the family and the community response, are we talking about the fact that they also have to get together to coordinate the roles and responsibilities?

YG Yes, to coordinate and also to mourn them, the deceased.

KM Is that the same response for Dhuwa and Yirritja moieties?

YG Yes, both for Dhuwa and Yirritja and to make sure people from the two sides of Dhuwa and Yirritja always have to work together.

KM Like the custodian or the djuŋgaya [caretaker, manager or custodian who inherit rights and responsibilities to land and ceremonies via their mother’s clan].

YG Yes Djuŋgaya or Waku-wa_taŋu [sister’s son, designated handler of bodily remains], could be, Gathu-wa_taŋu [the proper patrilineal great grandfather’s clan]. They all have to work together to coordinate the ceremony.

KM Do clans do it differently?

YG Clans do it differently and according to their cultural protocol, like songlines or sand sculptures and there could be other objects that they make, or display and put in place, like ceremony and song. But the ceremonial song cycle they have to do goes from the start, from the beginning, as you know, from the horizon, from where the horizon is coming up and all the way down towards the inland Country. The sand sculpture [yiŋapuŋapu] that I mentioned is very important for the person, because that is the way it goes down deep into the ground. It opens the way for that person to go deep in the ground because our bundurr, bones, will go back to the Country, where we are coming from.

KM So your bones will return back to the Country?

YG Yes, the bone and also the flesh. The spirit will go back to the Country too, to where they have been going through, where they have been moving through, along the coastal area or along the inland Country.

KM So the spirit goes back to their ancestral birthplace?

YG Yo [Yes].

KM So for the spirit to go back, for the soul to return to the ancestral domain, is it essential that the appropriate songs, manikay [songlines] and buŋgul [dance] are practised?

YG Yeah, through the song cycle and ceremonial way of putting the person back to the Country.

KM Who organises those ceremonies, when you talk about the custodian or the djuŋgaya?

YG The main person in my clan. My clan have to decide, or the other relatives, like Gutharra [maternal grandchild] or Märi [maternal grandmother] or other relatives, family members.

But the owner who runs that particular ceremony, he is the one to give the responsibilities and authority to djungaya mala [caretaker (of the clan)] or to any other relatives like Waku-wa_taŋu [sister’s son, designated handler of bodily remains] or Ŋän_d_i-wa_taŋu

[the proper mother clan], mother and child.

KM Is it important that all the appropriate people participate in this ceremony?

YG Yes of course, in our world, we always go and participate, all Yolŋu mala [clan or clans].

KM When you talk about these ceremonies is it less about the individual and more about a community as a collective of people, that help take that individual’s spirit back to its ceremonial birthplace?

YG Yeah.

KM Like a whole clan, like gurru_tu [kinship or Yolŋu foundation1] in a way?

YG Yeah, all clan, gurru_tu.

KM Everybody has their purpose and their responsibility in that Yolŋu law.

YG Because of gurru_tu. Without gurru_tu we aren’t connected to each other, we aren’t connected to the Country and the clan estates.

KM In a way you could say that each person has a greater sense of community in their role, rather than like balanda [non-Indigenous person] where it’s about the individual, this is about everybody having a purpose yeah?

YG Yes.

KM And that purpose is defined through gurru_tu?

YG Yes. Way back, very very way back. Way back when the old people were here, and when someone died, they put that person into the platform shelter and leave it for another couple of months or years and then they go back and then they make big ceremonies and sand sculpture and cut hollow log and put the bones back to the _larrakitj [hollow memorial pole]. Then they put that person back

to their Country, but also other areas, when they die in another area and they will make the ceremonial connection to that Country where that person is coming from.

KM And then after that, many years later, the ceremony of the _larrakitj is practiced yeah, or months later. Can you tell me a little bit about what is the purpose of the _larrakitj and what was its role,

or what is its role still? Not about the art, but about the time when it was used for burial.

YG Well, the purpose of the _larrakitj, the way our old people used to use it, way back when there was no coffin, that’s why they made the _larrakitj, to put the persons bones into the _larrakitj. That is the purpose, so that person can go back to their Country and they make clan designs to go with it, miny’tji [clan designs or patterns].

KM That miny’tji, that clan design, does that relate to that person who has died?

YG It has to be coming from a very close relationship, like Märi [maternal grandmother] and Gutharra [maternal grandchild] or the owner like Walkur [great grandchild, patrilineal line], what we call Walkur.

KM When the ceremony is happening, do the people participating in the ceremony have designs painted on their body or gapan [white clay] on their forehead? If so, how does that relate to the funeral ceremony?

YG They put white clay all over the body and also red ochre as well. That is the very important thing that Yolŋu people use so they can go and mourn, and they can go free and close to that area where they are having the Bäpurru [funeral ceremony]. It protects them in away.

KM But now when we go into the art centre and we see _larrakitj being painted by different artists including yourself and other people like Gunybi Ganambarr pushing the boundaries, how do you see that transition now? How has the purpose of the _larrakitj changed to serve a contemporary art function? Does it still represent the same thing?

YG Yes, it still represents the same thing through gurru_tu and through that person who does the painting and puts that miny’tji on the _larrakitj, according to gurru_tu you know, because they want to describe that Country you know through the miny’tji.

KM I mean they’re not just beautiful patterns are they? They’re still related to –

YG They’re still related to that Country and to the ceremony and to gurru_tu. What they call that Country, for example, what I have to call my clan or any other clan next to us, you know? I can call it Ŋän_d_i [mother] or Waku [nephew], or it could be another relative.

KM What was your relationship to Mr Wunuŋmurra?

YG He is my cousin and we are both Dha_lwaŋu, and we are both speaking one language, but two homelands, Gurrumuru and Gän_gän, and also Garrapara. We all share in the expertise together, all of us, all Dha_lwaŋu people. And the person [Mr Wunuŋmurra] is my cousin and I have my family here with me, from his side.

Like my wife. I married one of his nieces.

KM He was a good man huh?

YG Yo. He was a good man and his father was a very great artist and he was a law man as well, and humble and gentle man. And he was a knowledgeable man.

KM Any thoughts on Mr Wunuŋmurra’s work on his mokuy or bark paintings?

YG Mokuy is the spirit woman, also I didn’t mention the spirit woman lives in that Country too at Garrapara, the other one right in the land, right in the middle of the area there near Baraltja, what they call Balambala, between Gän_gän and Baraltja, a place called Balambala. That’s where the other spirit lives on that Country too and also around in this area where the mokuy is. What does it say about this work?

KM It says that these are happy spirits. They are going home.

The spirits come in together Dhuwa and Yirritja to the sacred ground called Balambala, past Gän_gän, the other side for all the mokuy to get together.

YG That’s the place that I mentioned, Balambala. In our creation story Balambala is the place where they are making yid_aki and they were blowing the yid_aki in each direction to Baraltja which is for the Bitharrpuyŋu Mokuy and Gu_lgu_lmi Mokuy which is coming from another Mad_arrpa clan, from a place called Gayngarra next to the Baykultji area, and also to the Baykultji which is the Ŋun_d_urrpuyŋu Mokuy and also this way down towards Bokuy where the turn off is to Bäniyala. That’s where a place called Bokuy is. And that’s where, from Balambala it was calling, blowing yid_aki, Gan’bulapula mokuy making the yid_aki and also making very special things, what they call yuwan [ceremonial object/yam] and calling to each Country, to bring all the different spirits together where they have been having ceremony there in Balambala. I have a recording there from my grandfather talking about what I am talking about.

KM So this story, although Mr Wunuŋmurra made sculptures and paintings, this story exists before him and will continue to exist way beyond him.

YG Yo.

KM Can you talk a bit about Mr Wunuŋmurra’s work and how it relates to the songs of Garrapara, Muŋurru and the journey of the spirit?

YG Well, we always tell it straight and always put it into our artwork or into our ceremony and into our words, talking about the Country which is the saltwater Country, and as the water’s coming in and out, rushing and bringing new things, new life, to the Country, and that comes up to the shore where the land is. That’s where our bones go back to Country, to the ground, to the soil, like yiŋapuŋapu.

KM And the spirit?

YG Back to the Country where the deceased person belongs or is coming from.

KM It’s like a cycle yeah?

YG Yeah, it’s a cycle we go back to and when someone passes away, a beloved one passes away, that person also keeps coming to that family and be with them, but we all know they go back to where they are coming from.

KM Can you do a couple of lines of that manikay, of that song?

YG When we go out to the ocean, we caught some fish, then we go back to the land, to the shore and we start to eat that fish and we put that fish back to the Country. That is the way to put that fish back to that, to the ground. We are putting all those bones, flesh back to that, to the ground.

KM Same like in the Bäpurru [funeral ceremony] way.

YG Same like Bäpurru.

Yinimala Gumana is a Yolŋu man of increasing authority, cousin of Nawurapu Wunuŋmurra and member of the Dhalwaŋu clan. Gumana has been anointed as

a future Dalkarra/Djirrikay (leader of Dhuwa and Yirritja ceremonies). He is a practising artist and member of the managing committee at Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala, where he was also elected Chairperson in 2011. Gumana is co-curator of the exhibition Madayin at Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection, University of Virginia, USA.

Kade McDonald is the Executive Director of Durrmu Arts Aboriginal Corporation and was the Coordinator of Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre for six years. McDonald is the Australian project manager and a co-curator of the exhibition Mad_ayin at Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection, University of Virginia, USA.

Garrapara (detail) 2012

1. For a detailed description of gurru_tu see Nici Cumpston, ed., Tarnanthi: Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art, (Adelaide: Art Gallery of South Australia, 2019).

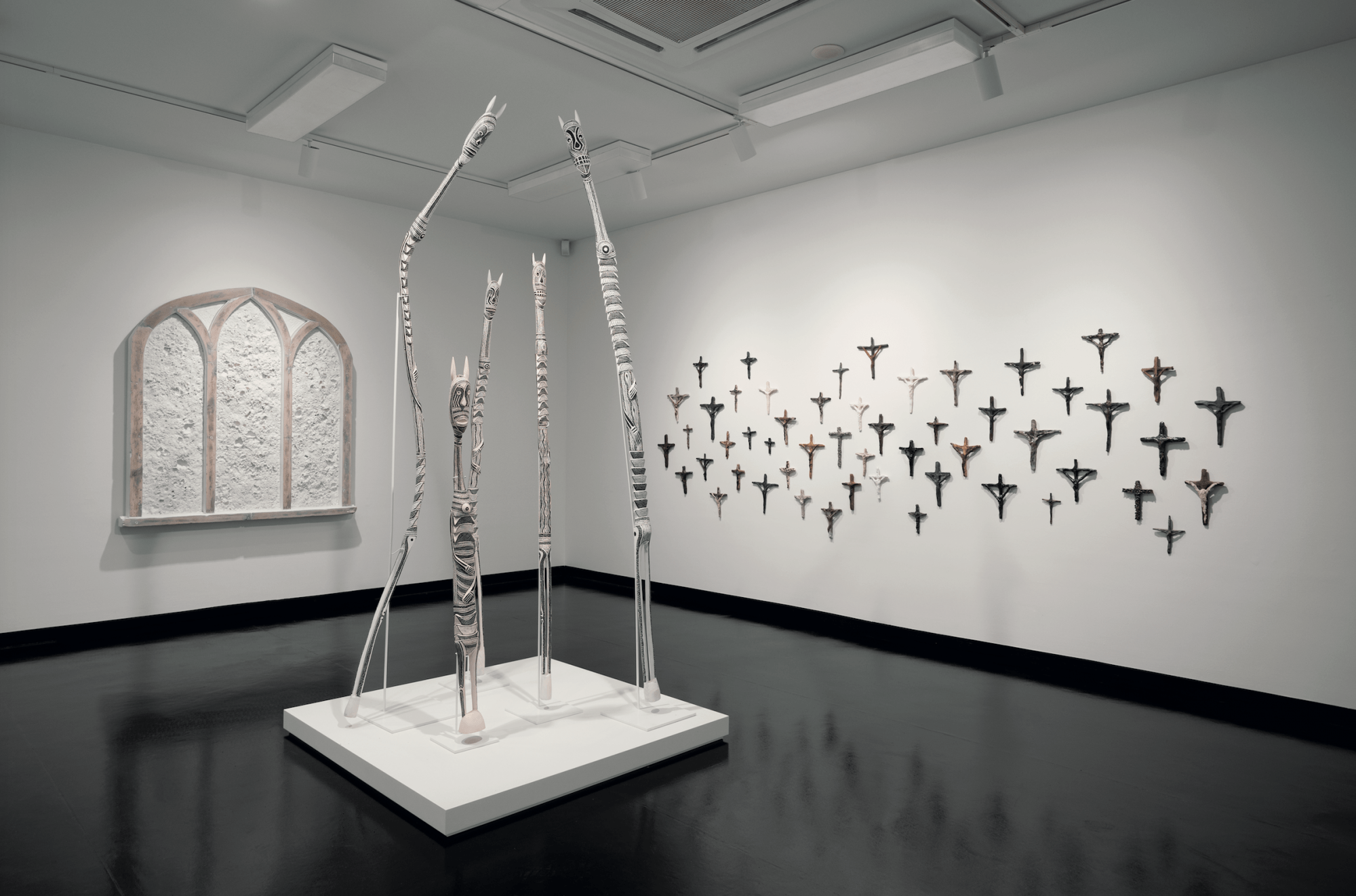

Michael Needham

Interstice 2017

Nawurapu Wunuŋmurra

Mokuy 2012

Richard Lewer

Crucifixes 2018

Installation view, La Trobe Art Institute, 2020

Photograph: Ian Hill

Crucifixes (detail) 2018

Voices and footsteps echo and decay from room-to-room. Cool, dry, filtered air circulates, constantly moving around your body.

![Michael Needham Monument to Muther [sic] 2020 Installation view, La Trobe Art Institute, 2020 Photograph: Ian HIll](https://netsvictoria.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Screen-Shot-2022-01-21-at-9.51.36-pm.png)

![Michael Needham

Monument to Muther [sic] (detail) 2020

Installation view, La Trobe Art Institute, 2020

Photograph: Ian HIll](https://netsvictoria.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Screen-Shot-2022-01-21-at-9.51.47-pm.png)

Monument to Muther [sic] (detail) 2020

Installation view, La Trobe Art Institute, 2020

Photograph: Ian HIll

![Michael Needham Monument to Muther [sic] 2020 Installation view, La Trobe Art Institute, 2020 Photograph: Ian HIll](https://netsvictoria.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Screen-Shot-2022-01-21-at-9.52.09-pm.png)