Roderick Sprigg

Roderick Sprigg is a multi-disciplinary artist whose process and communitybased art practice centres on the politics of masculinity in regional communities. He gained his Bachelor of Arts (Visual Art) from Curtin University in 2006, which incorporated an exchange at the Ecole Nationale Superior d’Art in Dijon, France. Sprigg has participated in numerous exhibitions, from Year 12 Perspectives at the Art Gallery of Western Australia (1996) to Ceci n’pas une Usine in France (2006) and at Fremantle Arts Centre (2008). In conjunction to various group and solo shows, he has also carried out residencies at The Cannery (Esperance, 2007), the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (2008) and is currently preparing for a residency at the International Art Space (Kellerberrin, 2009).

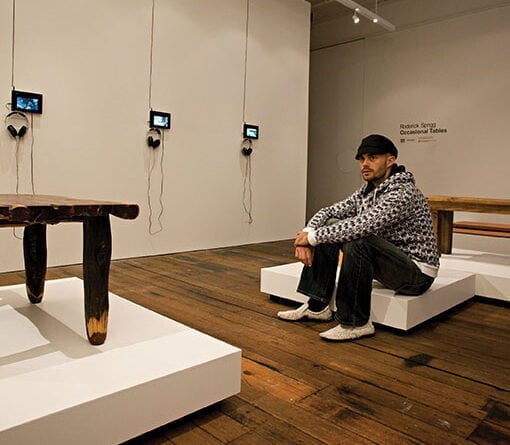

Occasional Tables investigates the myth of manhood and inter-generational relationships in Sprigg’s hometown of Mukinbudin, Western Australia. Over the course of this project, Sprigg facilitated a carpentry workshop where family members worked together to build self-designed coffee tables. These physical objects marked a time in a father and son’s life away from the farm, coming together (albeit at the invitation of the artist) to create purely for the sake of creating. Filmed from above as they worked the participants became performers as they crafted wood and memories in the accompanying documentary video installation.

Interview with Roderick Sprigg

Mukinbudin-based artist Roderick Sprigg is interviewed by father and daughter John Smith and Ann Brandis, participants in Roderick’s Occasional Tables project. Mukinbudin is around 300 km east of Perth, WA.

Ann Brandis: With your [Occasional Tables] project you got John’s shed involved, as well as friends and the community. What did you think would happen from your project?

Roderick Sprigg: I wasn’t sure how people would connect with it. But I knew the people and I knew who would be interested, so it’s a lot easier to get people excited when they personally know the artist.

AB: Dad, it got you involved, when you wouldn’t have been involved in anything artistic in your life.

John Smith: No. I’m probably artistic in that I can see something in a piece of metal that I need to make that other people can’t.

AB: So would you do another project like that?

JS: Depends what it is. What started it off?

RS: I began getting interested in narrative when I was at university and I asked my Dad about the time he found out that his brother had been killed. That conversation made me realise that blokes find it hard to communicate with other blokes, and got me interested in the reasons why. Is that just the way it is, or is there something different? Should we communicate more?

But the important thing about the table project was the volunteering of the fathers and sons, or in your case father and daughter. As soon as you said, ‘I want to be involved’ you became the audience for me, so it was directly involving the audience.

AB: So it was about the relationship…

RS: Exactly. It was an investigation into how much time people spend with each other, or whether they want to spend time with each other. I tended not to talk about it as an art project, more as a community project.

AB: It broke down the barriers, didn’t it?

RS: Yes, it broke down the barriers. People were more accepting of being part of a community project.

AB: I think a fantastic outcome of your project was the art night. You had all sorts of people listening to contemporary art and to the [Artistic] Director of the Next Wave Festival, Jeff Khan, who would never normally have contact with those people.

RS: Yeah. [Mukinbudin farmer] Graeme Seaby came up to me afterwards and said, ‘I’m still thinking about what you said the other day!’

AB: But that’s good! Gets different views out there.

RS: Yes, people like Graeme would never go to an art talk, although I think he’s quite interested secretly. I guess people are scared of what they don’t know, they’re a little worried because they don’t understand.

AB: So, what kind of artist do you think you are?

RS: The first thing I look at is who my audience is. If my audience is regional, I try to meet them where they are. I say, ‘How am I going to connect with the people of Mukinbudin?’ The good thing about the table project was it incorporated the people in ‘Muka’ and connected with the Melbourne audience by showing them something new, something about regional Australia that people are interested in. But it also verified their world-view; they could connect on the romantic idea that people like spending time with family, and love their family.

AB: What is it like being an artist in Mukinbudin? Mukinbudin’s quite a straight community, although it’s become more accepting. Is it difficult here?

RS: For the artwork that I’m doing I find it easier. Mukinbudin is not very varied, it doesn’t have outside influences, a lot of our culture and background is similar. I find it good because it’s what I understand, so I can easily comment on it. So I like it in ‘Muka’.

JS: What about seeding and harvest time, does that interrupt?

RS: I try not to take time off then. I feel sorry for the farm because I don’t do much work, I’m always driving here, there and everywhere.

AB: But you get lots of community support don’t you? Mukinbudin’s recognising you as a really good artist. Do you plan to stay here and keep doing art?

RS: It depends what my art does and how busy I get. At the moment it’s working out well for me but I’m not sure how well it’s working out for the farm!

AB: Do you exhibit anywhere else?

RS: I’ve got a show at Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, and one at Fremantle Arts Centre in December. I have a sculpture in that one and I’m making a big table guard. Exploring the metaphor of how blokes go out in tractors and take off all the guards to work easier. Then they come home and struggle to communicate with their family, so they’re putting their guards back on. I’m making a ‘guard table’.

AB: That’s a real theme in your art isn’t it? The communication and relationships between people.

JS: See somebody driving a harvester or a tractor would understand that, but somebody in Perth would not have a clue.

RS: That’s very true. I tend to deal with metaphors so country people go, ‘Yeah I get that’ and city people analyse it as an art object and ask the meaning afterwards.

February 2009Roderick Sprigg is a multi-disciplinary artist whose process and communitybased art practice centres on the politics of masculinity in regional communities. He gained his Bachelor of Arts (Visual Art) from Curtin University in 2006, which incorporated an exchange at the Ecole Nationale Superior d’Art in Dijon, France. Sprigg has participated in numerous exhibitions, from Year 12 Perspectives at the Art Gallery of Western Australia (1996) to Ceci n’pas une Usine in France (2006) and at Fremantle Arts Centre (2008). In conjunction to various group and solo shows, he has also carried out residencies at The Cannery (Esperance, 2007), the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (2008) and is currently preparing for a residency at the International Art Space (Kellerberrin, 2009).

Occasional Tables investigates the myth of manhood and inter-generational relationships in Sprigg’s hometown of Mukinbudin, Western Australia. Over the course of this project, Sprigg facilitated a carpentry workshop where family members worked together to build self-designed coffee tables. These physical objects marked a time in a father and son’s life away from the farm, coming together (albeit at the invitation of the artist) to create purely for the sake of creating. Filmed from above as they worked the participants became performers as they crafted wood and memories in the accompanying documentary video installation.

Interview with Roderick Sprigg

Mukinbudin-based artist Roderick Sprigg is interviewed by father and daughter John Smith and Ann Brandis, participants in Roderick’s Occasional Tables project. Mukinbudin is around 300 km east of Perth, WA.

Ann Brandis: With your [Occasional Tables] project you got John’s shed involved, as well as friends and the community. What did you think would happen from your project?

Roderick Sprigg: I wasn’t sure how people would connect with it. But I knew the people and I knew who would be interested, so it’s a lot easier to get people excited when they personally know the artist.

AB: Dad, it got you involved, when you wouldn’t have been involved in anything artistic in your life.

John Smith: No. I’m probably artistic in that I can see something in a piece of metal that I need to make that other people can’t.

AB: So would you do another project like that?

JS: Depends what it is. What started it off?

RS: I began getting interested in narrative when I was at university and I asked my Dad about the time he found out that his brother had been killed. That conversation made me realise that blokes find it hard to communicate with other blokes, and got me interested in the reasons why. Is that just the way it is, or is there something different? Should we communicate more?

But the important thing about the table project was the volunteering of the fathers and sons, or in your case father and daughter. As soon as you said, ‘I want to be involved’ you became the audience for me, so it was directly involving the audience.

AB: So it was about the relationship…

RS: Exactly. It was an investigation into how much time people spend with each other, or whether they want to spend time with each other. I tended not to talk about it as an art project, more as a community project.

AB: It broke down the barriers, didn’t it?

RS: Yes, it broke down the barriers. People were more accepting of being part of a community project.

AB: I think a fantastic outcome of your project was the art night. You had all sorts of people listening to contemporary art and to the [Artistic] Director of the Next Wave Festival, Jeff Khan, who would never normally have contact with those people.

RS: Yeah. [Mukinbudin farmer] Graeme Seaby came up to me afterwards and said, ‘I’m still thinking about what you said the other day!’

AB: But that’s good! Gets different views out there.

RS: Yes, people like Graeme would never go to an art talk, although I think he’s quite interested secretly. I guess people are scared of what they don’t know, they’re a little worried because they don’t understand.

AB: So, what kind of artist do you think you are?

RS: The first thing I look at is who my audience is. If my audience is regional, I try to meet them where they are. I say, ‘How am I going to connect with the people of Mukinbudin?’ The good thing about the table project was it incorporated the people in ‘Muka’ and connected with the Melbourne audience by showing them something new, something about regional Australia that people are interested in. But it also verified their world-view; they could connect on the romantic idea that people like spending time with family, and love their family.

AB: What is it like being an artist in Mukinbudin? Mukinbudin’s quite a straight community, although it’s become more accepting. Is it difficult here?

RS: For the artwork that I’m doing I find it easier. Mukinbudin is not very varied, it doesn’t have outside influences, a lot of our culture and background is similar. I find it good because it’s what I understand, so I can easily comment on it. So I like it in ‘Muka’.

JS: What about seeding and harvest time, does that interrupt?

RS: I try not to take time off then. I feel sorry for the farm because I don’t do much work, I’m always driving here, there and everywhere.

AB: But you get lots of community support don’t you? Mukinbudin’s recognising you as a really good artist. Do you plan to stay here and keep doing art?

RS: It depends what my art does and how busy I get. At the moment it’s working out well for me but I’m not sure how well it’s working out for the farm!

AB: Do you exhibit anywhere else?

RS: I’ve got a show at Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, and one at Fremantle Arts Centre in December. I have a sculpture in that one and I’m making a big table guard. Exploring the metaphor of how blokes go out in tractors and take off all the guards to work easier. Then they come home and struggle to communicate with their family, so they’re putting their guards back on. I’m making a ‘guard table’.

AB: That’s a real theme in your art isn’t it? The communication and relationships between people.

JS: See somebody driving a harvester or a tractor would understand that, but somebody in Perth would not have a clue.

RS: That’s very true. I tend to deal with metaphors so country people go, ‘Yeah I get that’ and city people analyse it as an art object and ask the meaning afterwards.

February 2009