Simryn Gill: Inland—

Artists: Simryn Gill

Simryn Gill: Inland is the first survey of photography by Singapore-born, Sydney and Malaysia-based artist Simryn Gill, drawing upon works created over the past two decades. While photography forms a significant part of her practice, the artist does not consider herself to be a photographer. Simryn Gill: Inland embraces this conundrum as an entry point for considering Gill’s artistic practice, and how photography might function more broadly as a way of engaging with the world.

This expansive survey includes selections from Gill’s series Forest (1996-1998),Rampant (1999) and Vegetation (1999) as well as the iconic Dalam (2001). Further works include the highly personal Power station (2004) and Distance(2003-2008).

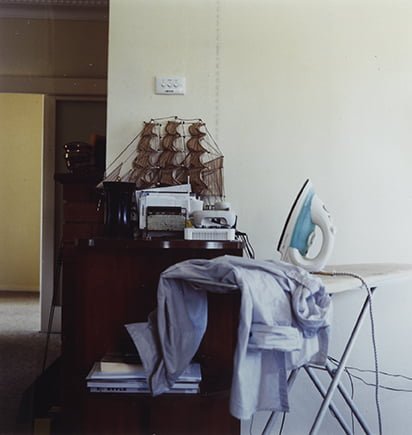

A feature of the exhibition is the presentation of Gill’s most recent work Inland (2009), commissioned specifically for this survey with support from the Australia Council for the Arts. The work is an intimate series of hand processed Cibachromes which emerged out of a journey from northern New South Wales across to Western Australia, surveying interior images of homes she visited, while eschewing the predictable tropes of representing rural Australia.

Gill has exhibited extensively in Australia and internationally including solo projects presented at Tate Modern, London, UK; Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, USA; CCA Kitakyushu, Japan; Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki, Finland; Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney; and Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne.

Developed by Centre for Contemporary Photography (CCP) and Melbourne International Arts Festival, Simryn Gill: Inland has been curated by CCP Director Naomi Cass. Selected works from Simryn Gill: Inland will tour to five regional Victorian venues in 2010 and 2011 with NETS Victoria and support from the Melbourne International Arts Festival.

Interview

Simryn Gill: Inland is the first survey of Gill’s photography and presents the second in CCP’s biennial series of mid-career surveys. While photography forms a significant and wondrous part of her practice, Gill does not consider herself a photographer. In this email interview, she speaks with exhibition curator Naomi Cass, who begins by asking Gill about her new series Inland 2009, commissioned by CCP for this exhibition.

This interview was orginially published in FLASH issue 3 2009. It is reproduced here courtesy of the Centre for Contemporary Photography.

Naomi Cass (NC): At the centre of CCP is a small gallery housing your series Inland 2009. Gallery 4 is largely empty except for a rather ordinary office table and stools. The walls are bare. On the table are 162 prints, 13 × 13 cm each in several piles, and a few pairs of white gloves, inviting visitors to sit down, put the gloves on and explore the prints. Within each pile are three types of images: cibachrome photographs of interiors; black and white landscape photographs and a third group of studio cibachromes. Can you describe what the three different groups of photographs are and why they are taken in these different modes?

Simryn Gill (SG): The photos were taken during a journey through New South Wales and South Australia. When I asked people if I could photograph their homes, I described what I was doing as ‘trying to photograph the interior through interiors’. So perhaps the pictures of the insides of homes and the pictures of the out-there, the landscape, if you like, are both versions of interiors. The stones were also collected during the trip. And then they became part of the picture of the interior that we had made. Yet another version. But these three versions, to become a set, needed to exist in the same form, on the same plane. Inevitably the stones had to meet the other two and be photographed to be included as equals: homes, wilderness, farmland, clouds, road, stones, rocks, fossils, glass shards, shells. Of course it’s an absurd proposition – it could be the other way around – for the homes, the landscape places, the clouds, to match, to meet the form of the stones and shards, as a real, physical, set of collected ‘objects’.

Regarding the choice of colour and black and white film: no reason, really, that I can offer. I think I wanted to see how the bush would translate into black and white. It’s so colourful.

NC: There is something humble about this installation. It is really quite surprising given the preciousness attributed to photographs within an exhibition context. Indeed, visitors to the survey walk through, or past, six major bodies of work variously and precisely installed in grids, or restrained in some way by their framing or installation, before reaching Inland. All bets are off in Gallery 4, our bodily relationship to the photograph is changed. This simple gesture is more akin to viewing vernacular or family photographs. Can you comment on the active relationship the viewer has with this work?

SG: When I was looking at initial test prints of the photos, picking them up, putting them down, shuffling, arranging, I realised that that was how I wanted them to be seen, with that same physical proximity, the same access, and also that tenderness. I had no idea if people would be responsive to such an offering, if they would want to take the time to look in this way. But it felt like the right way to show them.

NC: Inland does have filial relationship with earlier series including Dalam 2001 in Gallery 3 and A small town at the turn of the century 1999-2000, one of which is exhibited in Gallery 1. While different in many ways, in both series the camera is gathering, collecting for a purpose and yet you are not a documentary photographer. Can you comment?

SG: Yes, the camera in these works is gathering, but I am not sure that the viewfinder is collecting for a purpose so much as simply looking. Like people-watching when one is sitting in a crowded place with a lot of time on one’s hands, such as an airport lounge, or a tourist place. The looking takes on a kind of absent-minded, day-dreamy search for order, but not with a purpose to explain or describe.

NC: You came to photography amidst a wide practice of collecting, tearing, arranging, casting, wrapping, rubbing and engraving, a practice that is at once hand made and yet highly intellectual. On the surface, photography is very different from these activities in being once removed, technical and often a practice remote from engagement with subject or materials, particularly considering digital technologies. Can you say something about what interests you in making photographs? And, by the way, do you use a digital camera?

SG: My first photo was a commission for artist pages in Art & Text. I made a banana skin wig for a friend in Singapore, a blonde wig, which, even if the photo did not tell you this, one knew would rot and turn black in a few days. Like Cinderella’s dress, waiting to turn into a pumpkin at midnight. I loved being able to work with this wet, icky material, in the way that I was used to, but also to be able fix it in a photo, in a way that implies the rot ahead. This and other early works were photographed for me. But when I started doing it for myself, I became entranced by how film has its own materiality too, like the banana skins. Films have their peculiarities: I loved the formal struggles of making a film do things against its grain, as it were. I loved that old idea of how film literally captures time and light inside itself. So perhaps I approach film as a material. And film taught me to approach time as a material.

I haven’t used a digital camera. I really like the constraints of film. The slowness of setting up. The focus, concentration, looking, as one may only have a few frames to do the job at hand. I love the freedom of not being able to check the results immediately, in the middle of working, so that one can, and must, lose oneself in the present actions and choices and trust one’s judgements. I am attracted to the discipline that the limitations of film demands.

NC: A survey of your photographic work in a media specific photography gallery was probably not something you were seeking. Has bringing work together from your earliest photographic series, Forest 1996-8 to the present, and including your only moving image work, Vessel 2004 placed an unnecessary emphasis on photomedia in your work?

SG: Well, I was somewhat uncomfortable about the idea. And I also felt that the repetitiveness and the scale of some of my series could make me seem a bit obsessive. But the density actually works very well I think, not least because of the way the gallery leads a viewer in an intense and unusual (for a gallery) spiral into a heart. A centre.

I think medium is beside the point. I’m quite sure I do the same thing in different materials. I’m not interested in iconic images, but in how we are informed through detail.

NC: In writing about a series not included in Inland, the series May 2006, you made a visceral analogy between the vigilant attention you give to detail in making a photograph and the vigilant attention an immigrant must pay to their new environment.¹ In many respects, much of the work exhibited in Inland is paying attention to traces of an individual or a community within a particular environment or place. I am thinking of Forest, Rampant and Vegetation 1999, Dalam, Power Station 2004 and Inland 2009. Do you think photography has a heightened ability to focus our attention on an issue, or is the medium overburdened by its indexical relationship to the real world?

SG: Wow, this is such a big question! I am not sure that these two disqualify each other. And I can talk about how I think I use photography, in that very ‘attentive to detail’ way, but not attentive to issue. Is looking at detail an example of indexical relationship? I don’t know. A picture is just that. Its like a glimpse which is frozen and then can be extrapolated and theorised and used to prove all kinds of real things – like the existence of WMDs in Colin Powel’s hands or, in John Howard’s hands, some photos of children in the sea in life jackets as proof that some ‘barbaric’ people wanting to come to Australia threw their children into the ocean to get sympathy. Or that there are fairies at the bottom of the garden, as shown in photographs by Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, those two young English girls who convinced ‘the best minds’ of the time that their elaborate hoax was real. All indexical relationships. To something.

¹ Simryn Gill, ‘May 2006′, Off the Edge, Merdeka 50 years issue no. 33, September 2007, p87.

2010

Learning Guides

-

Simryn Gill A small town at the turn of the century #5 1999–2000

type C photograph

from a series of 40

Courtesy the artist and Breenspace, Sydney -

Simryn Gill Vegetation #5 1999

silver gelatin photograph

Courtesy the artist and Breenspace, Sydney -

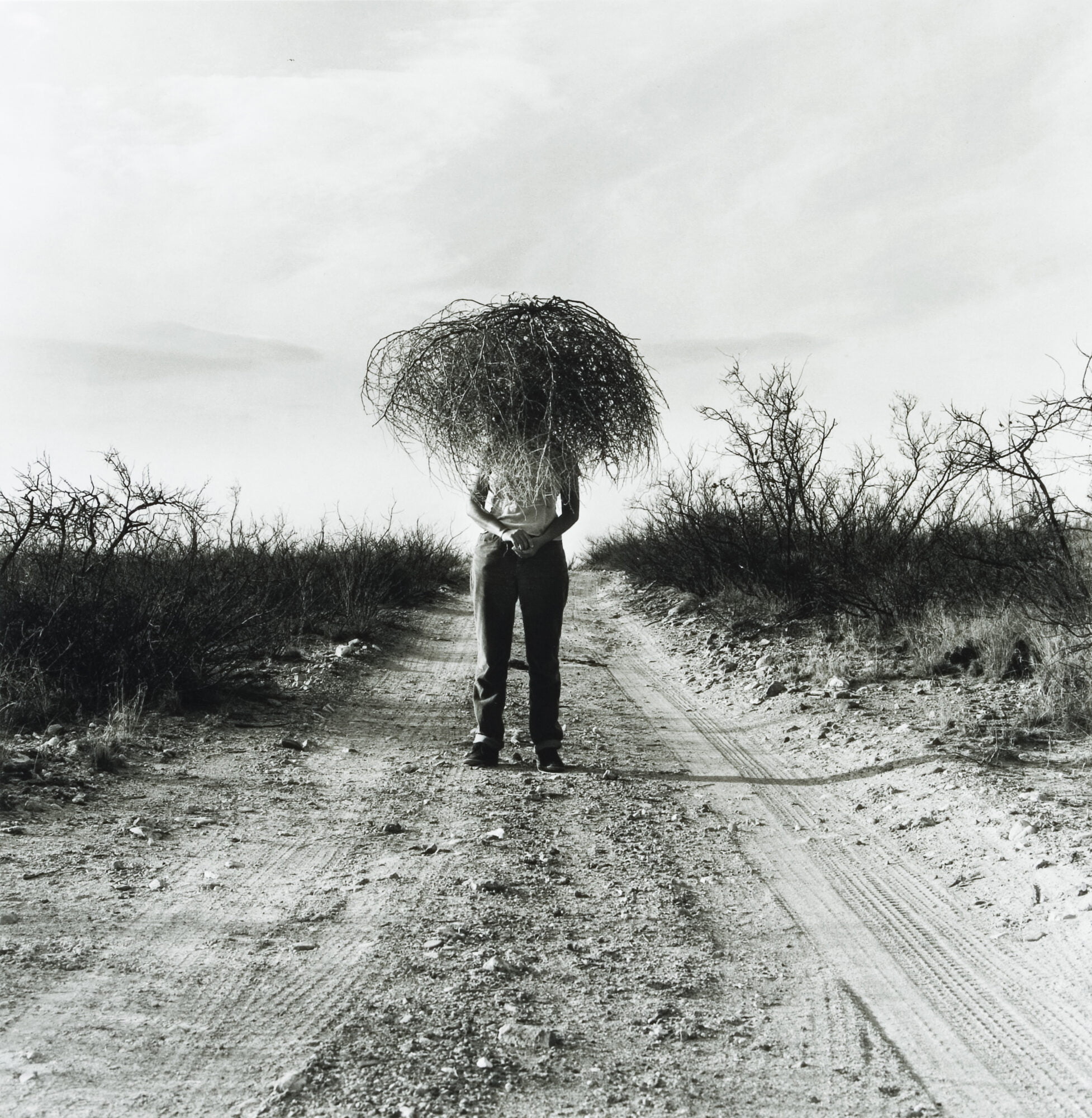

Simryn Gill from Power station 2004

13 type C photographs and

13 silver gelatine photographs

Courtesy the artist and Breenspace, Sydney -

Simryn Gill from Power station 2004

13 type C photographs and

13 silver gelatine photographs

Courtesy the artist and Breenspace, Sydney -

Simryn Gill from Dalam 2001

260 type C photographs

Courtesy the artist and Breenspace, Sydney -

Simryn Gill from Dalam 2001

260 type C photographs

Courtesy the artist and Breenspace, Sydney -

Simryn Gill from Forest 1996–1998

16 silver gelatine photographs

Courtesy the artist and Breenspace, Sydney -

Simryn Gill from Inland 2009

cibachrome and gelatine photographs

Courtesy the artist and Breenspace, Sydney