Manikay—

the song knows the destination

Wukun Wanambi

Edited by Kade McDonald

Death is related to life, life is related to death. The manikay (sacred song) is related to the Country. It doesn’t matter if you are gapu (water) Country or land Country, the manikay belongs to that place. If we sing about water, we can connect the people to that place.

We can know where it [manikay] comes from.

We can complete the whole manikay cycle with the Bäpurru (funeral). How do we know the story? Through the songline.

We can say: this song is about the wind and this wind can cycle around the body and move around to find the destiny and where it will be. The wind will pick the spirit and relocate it to his Country or place of destiny. The song knows the destination of the deceased’s resting place.

Wind

Wata marrtji burrburryun garrminydi,

Wata marrtji burrburryun gun_d_a nyurrunyurru,

burrburryun wata dhukuyuna,

burrburryun wata garrminydi wukid_i ga djok-Marrakulu Wukid_i.The wind cycle, north, east, south and west has blown across Marrakulu Wukid_i (resting place for Dhuwa moiety – Djapu, Dhudi Djapu and Djambarrpuyŋu clans).

When we do this, everything allows a natural way for the deceased to lay down quietly and be at one.

The gurru_tu (relationship) system, allows the family groups to come in, the Märi (grandfather/grandmother) comes in and takes over the element of moving the deceased. When Märi controls the time and moves the body then the other Yolŋu can come in (to ceremony) with bilma (clapsticks) and manikay to assist the Bäpurru.

The _larrakitj (hollow log coffin), before, the old people used to keep the bones in the _larrakitj. The bones would go into the _larrakitj. This is the old times but the song hasn’t changed. Nothing has changed. From the beginning to today.

We still plan the ceremony through Märi as we always have.

The Märi is responsible for all the things relating to the deceased.

Yolŋu can sing the manikay to bring the life of the spirit back to the Country and into the people of his clan so other people can be attached with the spirit as well, as we continue to move along the songline.

That songline is the Guwak (nightbird, Koel Cuckoo) and it tells where the spirit can go down, for Dhuwa that is Guwak, a bird.

Guwak nightbird

Burrkun yaliyali wayimbaba dilimdilim liya ŋäthi ŋarra yurru dhiyaku dharpatjiwu marawili wulŋultji’wu.

The night bird (Guwak) cries at Djarrakpi telling that someone passed away. The bird flew to Yilpara, Gän_gän and to different places letting people know and continues, the spirit went back on their journey, until it reaches the homeland where the deceased is resting in their home ground.

The water – the cloud touches us and we can cry, cry along the songline. The journey begins from where we hold it, then it travels across the sky, the water and the Country. He goes back to his own land. The spirit will find its destiny. If I die my spirit goes back to my Country, Gurka’wuy (Trial Bay).

It’s more about the spirit and its resting place in his Country. The spirit and body cannot move without song. The body can be here (Yirrkala) or anywhere but the spirit will go back to its rightful resting place, like for me its Gurka’wuy.

As the deceased is resting in peace and quiet, then we can sing the song cycle of the manikay, this is where the destiny of your spirit goes back into your Country. So when we say:

Wulata, Wulata, ro_lmi, ro_lmi marrŋal maypa gapu dha_lirr’yuna.

The spirit of deceased women or men returned from his/her journey to their Country.

The maŋan (cloud) sung by Djapu clan also tells the story of the deceased, people going back to their home.

When we bring the _larrakitj it represents the image of the deceased who has passed away. For Dhuwa or for Yirritja it’s the same thing. We don’t hide it, we put it up. It is the image of everything we see and for where the spirit goes.

This is the memorial. We see this as a _larrakitj but also as the songline, the place and the journey of the deceased.

You can sing the manikay of the journey. This is the beginning of the cycle of the journey.

Sun going down . . .

Walirr nhaŋal dhunbiryuna nyikthuna gulaŋthu warrarra dhunbiryuna.

As the sun is going down and changed colour to red or orange, the spirit is on their way to their Yirralka (homeland)

Honey (Yarrpany)

Rakiny malka ŋalyun yolŋu’wal mokuy’wal,

Murruymurruy’yurr ŋayi gularrwaŋa yothun mirmir’nha mandhulba.

Yothu gularrwaŋa barrku djalkthurr bala Gurkawuy’lil ga barrku djalkthurr Gowutjurr Raymaŋgirr.When the deceased one is resting, the special white string hanging above the deceased represents the Dhuwa Guku (honey).

The song continues and also the bees. The bees started their journey from Gurka’wuy and stopped at Raymaŋgirr. From Raymaŋgirr they flew again to the Wagilak tribe.

Our manikay never ends, it has been passed on from generation to generation. The manikay knows our destiny, it knows the destination.

Wukan Wanambi is a leader of the Marrakulu clan (Dhuwa moiety), an award winning artist and Director of The Mulka Project, the media centre at Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala. Wanambi recently exhibited with La Trobe Art Institute in unbranded (2019) and worked as curatorial consultant on the exhibition Miwatj (2018). He is a co-curator of the exhibition Mad_ayin at Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection, University of Virginia, USA.

Nawurapu Wunuŋmurra

Garrapara 2007

Garrapara 2007

Garrapara 2012

Background, left to right:

Patrick Freddy Puruntatameri

Purukuparli 2020

Waiyai 2020

Timothy Cook

Kulama 2013

Timothy Cook and Patrick Freddy Puruntatameri

Tutini (Pukumani pole) 2019

Tutini (Pukumani pole) 2020

Tutini (Pukumani pole) 2020

Installation view, La Trobe Art Institute, 2020

Photograph: Ian Hill

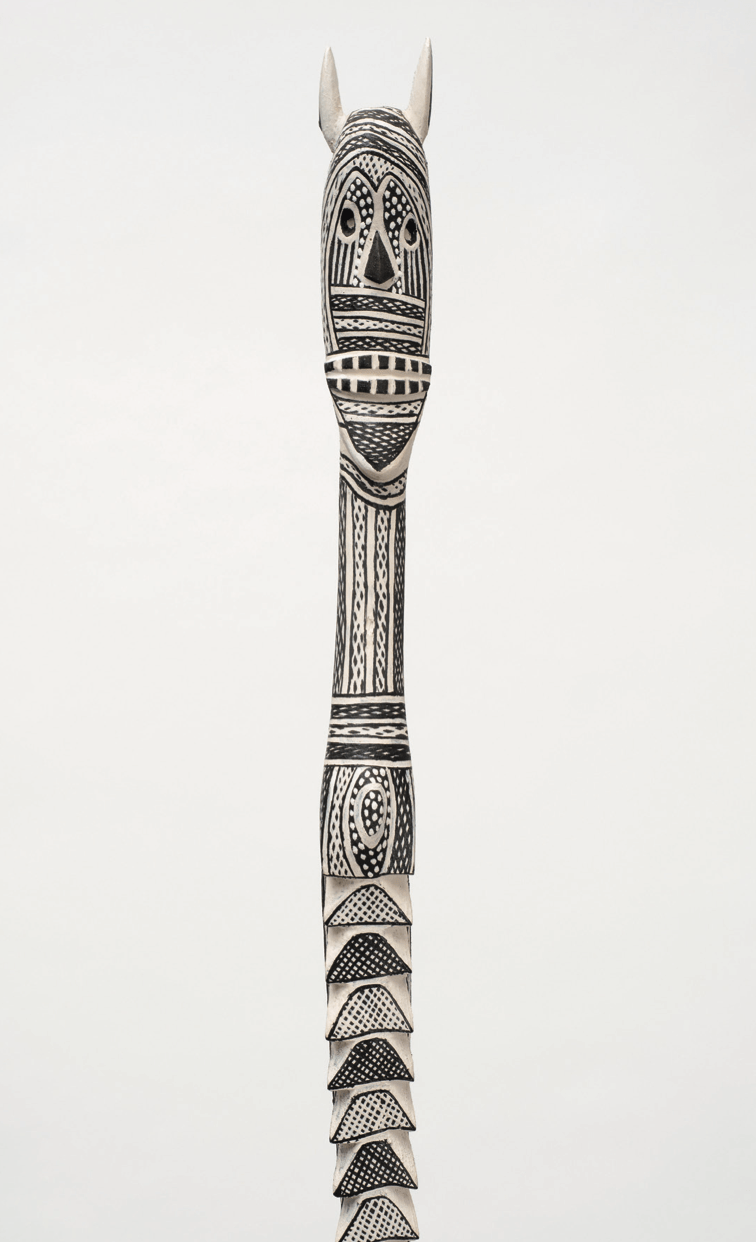

Mokuy 2012

Mokuy (details) 2012

Mokuy (details) 2012

Mokuy (details) 2012

Mokuy (details) 2012