GREAT MOVEMENTS OF FEELING—

Zara Sigglekow

arts writer, curator and administrator.

Emotion is a force, both cognitive and sensory, that occurs between things: people, concepts, and objects. It circulates, drives and sticks. With discursive and centrifugal ambitions, Great Movements of Feeling explores how select contemporary art practitioners observe emotion through personal and historic lenses. The title of this exhibition is lifted from the sociologist Emile Durkheim who ruminates on emotion that arises in

a crowd, acknowledging it originates from no particular consciousness. It speaks to emotions nebulous nature as

it circulates in the world. The feminist scholar Sara Ahmed argues that emotions exist as ‘impressions’ between things. According to Ahmed, the concept of the ‘impression’ is the

act of pressing on someone. As such, it clouds one’s ability

to distinguish between bodily sensation, emotion and

thought, as though they are experienced as indistinct realms. This conception brings together the two historical ‘camps’ of emotion theory: emotion as primarily tied to bodily sensations, and emotion as cognition. The works in this exhibition show facets of emotion congealing at different points on this spectrum: sometimes weighted towards a bodily sensation,

at other times towards a cognitive judgment—or somewhere in between. These artists wrestle with ideas of emotion, of content that is loaded with feeling, and at times where emotion might sit within art practice, touching on ethical, aesthetic, social, and the spiritual dimensions. In all, there is a sense of historical weight threading through: the inheritance of trauma, of love, of the passing down of feeling. A consideration of the past permeating the present, and complexity, because the past bleeds, and emotion bleeds, into the now.

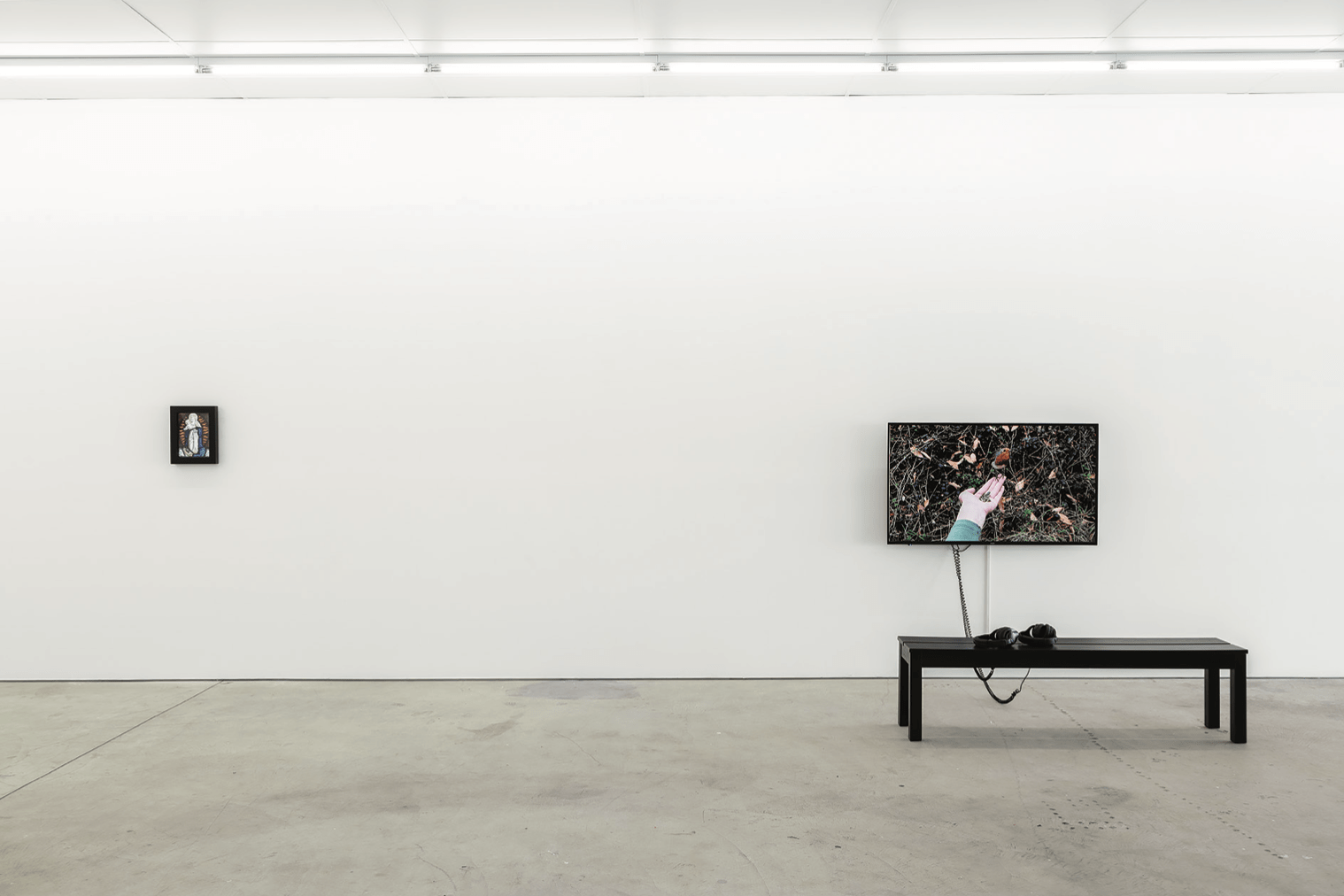

Themes considered include emotion within communication and the nature of voice. Sue Williamson’s It’s a pleasure to meet you 2016, explores the power and agency of testimony and stories, while Megan Cope responds to the emotional violence and the spectacle of trauma on social media

through an installation incorporating light, text and organic materials. The personal voice is also at play in Sriwhana Spong’s This Creature 2016, as she ruminates on the medieval mystic Margery Kempe, voice, and the pathological labelling of emotional expression. Art and artefacts have been carriers of affects throughout history, which is harnessed, questioned and, at times, subverted by artists in this exhibition. With this lineage kept in mind, included is a rare Medieval Flemish stained-glass window featuring Virgin Mary as ‘Lady of the Apocalypse’. Nik Pantazopoulos’s photographic triptych is

a ‘queering of modernism’ while maintaining the power of abstract affect. In Stuart Ringholt’s Anger Workshops 2012, the viewer becomes the art object, expressing emotion as catharsis, and Helen Grogan places objects under stress and performing crisis: an attempt to remove personal traces of expression and singular agency.

There is a civic and ethical undercurrent in the diverse make-up of the show. Artworks are indexes to, but are not beholden to society, and curation has a responsibility to

the social and political world. The works operate within a discursive framework, underscored by a perhaps utopian notion of encounter with difference: conceiving the exhibition as a cosmopolitan event. Cosmopolitanism is defined by academic Alex Lambert as:

Photo credit: Christo Crocker

…an event with two parts. The first is an encounter with difference. The second is a fidelity to this encounter. That is, a desire to learn from it, to be changed by it. This process, however, is never complete. In desiring the strange and the stranger we must also acknowledge that we can never interrogate, dominate, and internalise. Cosmopolitanism takes comfort in the eternal mystery of all that is other.1

When applied to the exhibition we can view the artworks as encounters of difference between themselves. That is, artworks placed beside each other with differing voices, in addition to the viewer of the exhibition encountering diversity.

This mode of cosmopolitanism is also reflected in the thematic framing of the show. A notion of ‘emotion’ is taking loosely so that the curatorial rational is not a polemic with the artworks acting as props, descriptions or examples of an argument.

As, ‘we can never interrogate, dominate and internalise’ our encounters with the ‘other’, here I do not seek to dominate the artworks in the exhibition but let them rest and speak from their respective positions. The exhibition becomes a space where artworks are encountered as nodes of difference (not necessarily just culturally, as the idea of ‘difference’ tends to be understood, but also in discrete subject matter and approach), and this encounter comes forth from a desire to experience what is different and get to know difference, but this desire is underscored with the impossibility of full knowledge of the works. If the gallery is conceived as a civic

space this approach could be viewed as a comment on, and perhaps a soft attempt to counter, the current social media polis which sees social spheres shrink to echo-chambers of likeness that aggressively encounter the ‘other’ in the comment sections.

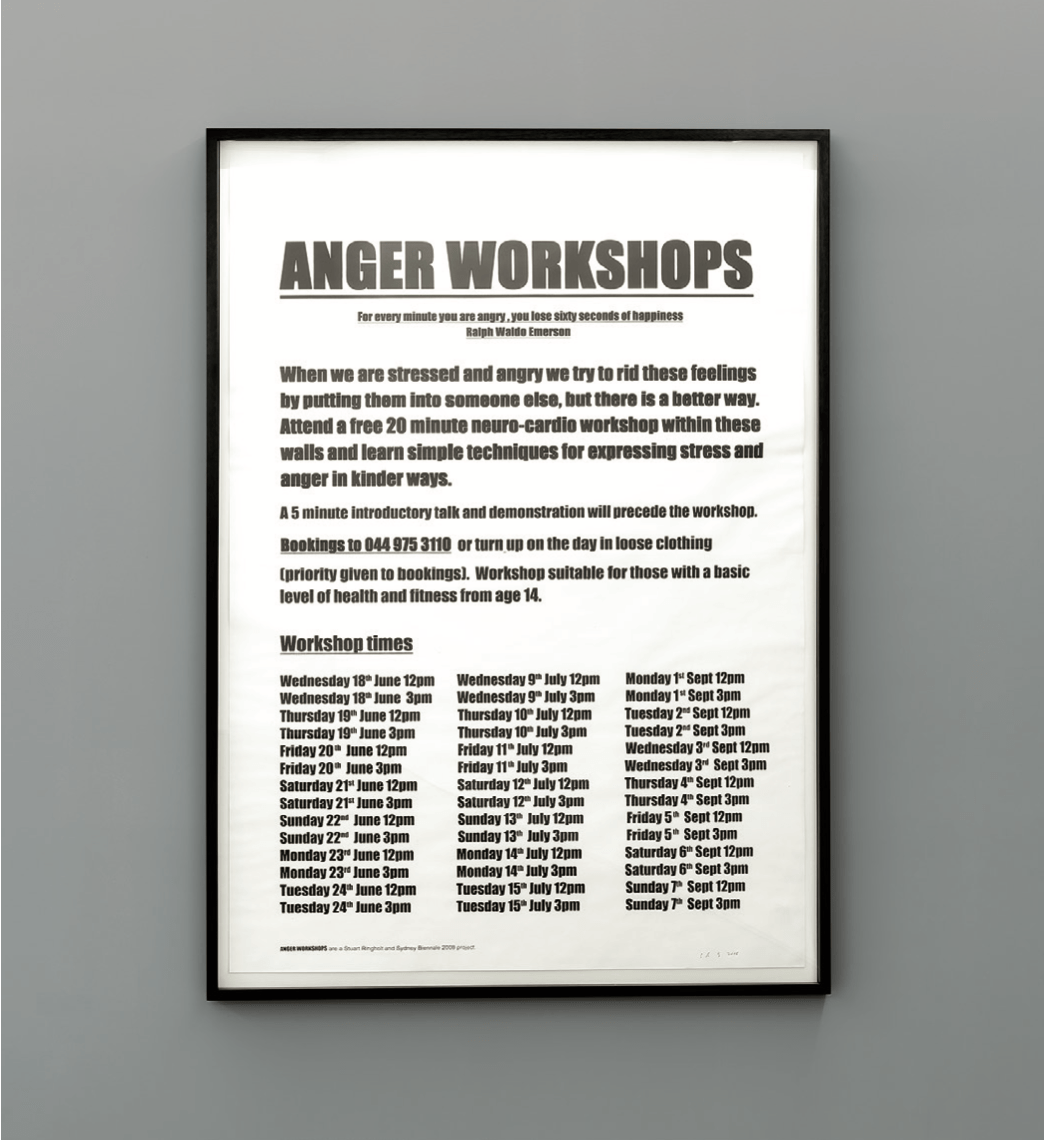

Anger Workshops 2008-ongoing

Poster from Public Workshop, Sydney Biennial, 2008 Courtesy the artist, Assembly New York and MADA, Monash University © the artist

Photo credit: Christo Crocker

1. mail correspondence with Alex Lambert

It’s a pleasure to meet you 2016

Two channel video: 24.4 mins

Image courtesy the artist and Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johanesberg, South Africa © the artist

Photo credit: Christo Crocker

A common element in the exhibition, however, as well as ‘emotionality’, is that these artists resist problems of emotion such as: spectacle, and violence, encouraging spaces that are softer, cathartic, and compassionate, while acknowledging

at times that negative emotions may well be a fundamental part of the human condition. This is in line with the idea the exhibition’s ethics, like a cosmopolitan event; in line with the notion that art that can be conceived, perhaps unfashionably and with contention, as nudging for a better world.

Stuart Ringholt’s Anger Workshops 2018, is predicated on

art for social benefit. Many works in his practice communicate a belief that art is not just for contemplation but can have a practical and therapeutic function. Anger Workshops, which has been performed in multiple locations (this poster is for

the Sydney biennial in 2012), is based on the Aum meditations created by the Indian spiritual leader Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. Visitors sign up to group sessions in a private room. There, they take part in an exercise that aims to provide experiences of emotion removed from judgement and the everyday. Participants are asked to express anger and then love, alternating between these two in what Ringholt describes as

a ‘neuro-cardio workshop’. This work creates a more (but not entirely) neutralised space in comparison to the outside world, where the circulating and sticking of emotion between people is mitigated, as participants are asked to express emotion not as a direct reaction to something. Another angle of emotion as the ‘impression’ between things, is considering the encounter between an artwork and the viewer as an ‘impression’: the artwork makes an impression onto the person who beholds

it, which can be an emotional encounter. When attending Ringholt’s workshops this traditional distinction is muddled, with the viewer becoming both the subject and object,

a pure expression of feeling that is closer to affect.

The complexity of anger connected to horrific personal

events is explored in Sue Williamson’s work It’s a pleasure

to meet you 2016. Williamson is part of a generation of South African artists who started making work in the 1980s as a way of addressing social change in what was then apartheid South Africa. Her artistic output is underwritten by a journalistic ethos of recording the stories of those around her. It’s a pleasure to meet you presents two young South Africans, Candice Mama

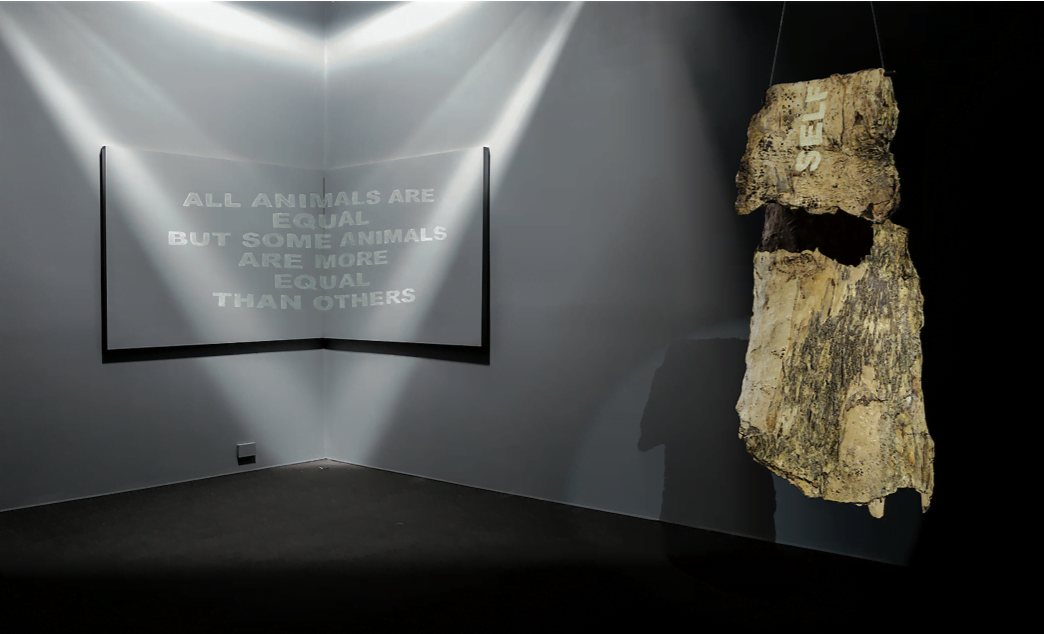

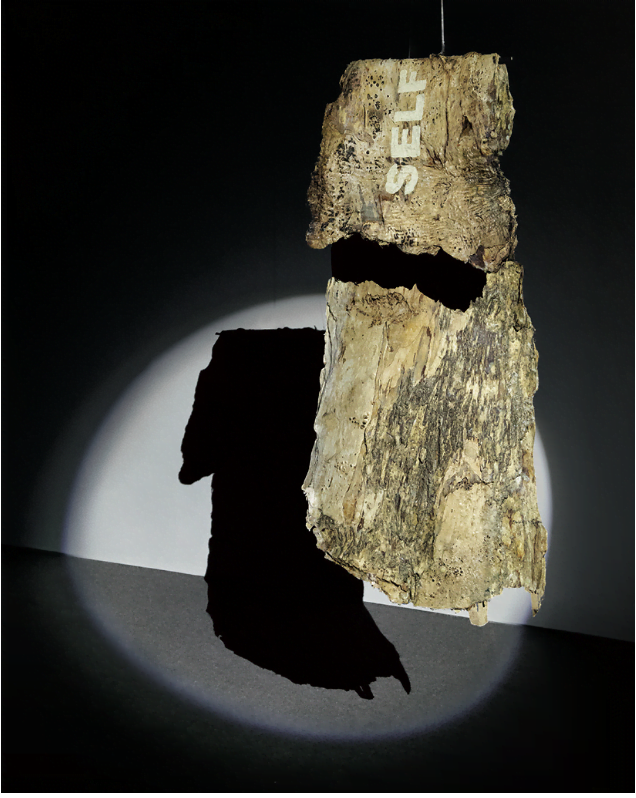

The Empire Strikes Black II (Self Determination) 2018 Oodgeroo (paperbark), Ochre and Beeswax

104 x 48 cm (approx.)

Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY + Dianne Tanzer Gallery, Melbourne © the artist

Photo credit: Christo Crocker

and Siyah Mgoduka, discussing the deaths of their fathers under apartheid South Africa. They reflect two positions:

that of a young man still filled with anger, and that of a young woman calmly describing her personal process of forgiveness. Artworks that tell stories of pain run the risk of becoming sensational, taking the power and agency away from those they belong to. Sara Ahmed stresses the importance of not fetishising pain to avoid divorcing it from its histories, and taking it on as ours, the viewer’s, own. She warns of how,

The negative emotions of anger and sadness are evoked as the reader’s: the pain of others becomes ‘ours’, an appropriation that transforms and perhaps even neutralises their pain into our sadness.2

Through a direct use of storytelling, Williamson creates windows of empathy with the viewer but allows the voices of Mama and Mgoduka to come through with texture, complexity and nuance. The work makes an impression on the viewer, but Mama’s and Mgoduka’s pain is never fully transferred.

In her installation consisting of two works, The Empire Strikes Black I (Some Animals are More Equal than Others) 2018 and The Empire Strikes Black II (Self Determination) 2018, Megan Cope critiques bullying and the spectacle of trauma on social media, in particular she comments on the trend of ‘calling out’ and identity policing as a form of lateral violence within the Indigenous community. In these cases, the quest for social media popularity takes priority over community responsibility, running counter to unifying minorities and connecting communities. Cope quotes George Orwell’s classic Animal Farm text, ‘All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others,’3 connecting the hypocrisy of the online behaviour she speaks of too Stalinist communism, suggesting that this is also a behaviour learnt from the oppressor. Cope creates a jarring sensorial environment in The Empire Strikes Black I (Some Animals are More Equal than Others) through the use of strobe lighting which illuminates the text and reflects the emotional and psychological mechanisms of this process, which she has been personally subjected to, and that all too often results in the ritual of violence as entertainment. The Empire Strikes Black II (Self Determination) is a softer counterpoint. A sculptural piece fashioned from Oodgeroo

2. Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, second edition, Edinburgh University Press, 2004, 2014, p. 21.

3. George Orwell, Animal Farm, New edition, Penguin, 2000.

The Empire Strikes Black I (Some Animals Are More Equal Than Others 2018

anamorphic text, Glow Mineral on board with timed strobe light

122 x 160 cm (x2)

Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY + Dianne Tanzer Gallery, Melbourne © the artist

Photo credit: Christo Crocker

(paperbark) from Cope’s homeland is covered in beeswax

and hangs in a draped form from the ceiling. Inscribed with the text ‘Self-determination’ in ochre, the work is both portrait of the artist’s body affected by this violence, and a reminder of the original political goal.

For these works Cope wrote the following text:

This is what it feels like to have strips torn off your back and hung out to dry, punched in the head and told to know your place.

This violence is not new. It’s what we’ve learned from the oppressor veiled in community service announcements, rationed violence through status updates.

There is an old saying: A Fish Rots from The Head Down.

Helen Grogan’s practice is concerned with systems of observing, sensing, and locating. She is hyper-aware of the ethical tensions of the subject viewing an object, an audience viewing a performer, and seeks to disrupt this relationship that can be fraught with power imbalance. splitting open the surface on which it is inscribed 2018, is an exploration of the agency of an object. That is, how to work with an object with limited subjective impact and reveal its materiality and agency, encourage a more sympathetic relationship between viewer and artwork, and the place/architecture within which it sits. The work consists of a 15-minute choreographic score, enacted for three different restrictive camera views and a detailed stereo audio recording. A thin mirror-finish steel

disk is forged, folded, and pressed by the score participant Shelley Lasica, revealing both resistance to her actions,

and compliance to her force. The manner in which Lasica undertakes her actions is sympathetic and adaptive to the object’s response. All the while, the surface reflects the room, actions, and apparatus around it. The visual replay of this event within the exhibition is fractured and dispersed across three screens, while the sonic re-articulation manifests as a synchronised real time diegetic audio recording. The sum of this effect is the creation of an embodied sensorial empathy between viewer, artwork, and gallery space in which it sits.

splitting open the surface on which it is inscribed 2018 Multi-channel video and sonic recording (14:50 min) synchronized and looped, with spatialised configuration.

Choreographic score design and development: Helen Grogan. Choreographic score enaction for Gertrude Contemporary foyer site: Shelley Lasica.

Sound Recordist: Liam Power

Courtesy of the artist and ReadingRoom © the artist Photo credit: Christo Crocker

This Creature 2016

single-channel HD video, sound

14:55 minutes

Image courtesy of the artist and Michael Lett, Auckland, New Zealand © the artist

Flemish stained-glass window, framed light box

c. late 15th century

27 x 20 cm

Australian Catholic University Art Collection Acquired 2017

Sriwhana Spong’s video work This Creature 2016, is also concerned with a softer side of emotion, but one attuned

to the senses and connected to a historical figure. Spong ruminates on the female Medieval mystic, Margery Kempe, who wrote the first recorded western autobiography. She films from her vantage point on an iPhone while walking around Hyde Park where she feels the surfaces of objects, feeds birds and observes her surroundings. Meanwhile, a voiceover reads her diaristic musings and thoughts on Kempe, who defied established institutions in favour of a relationship with God that was—in the manner of female mystics—through her senses. As a mystic, Kempe’s body was not experienced as a discrete entity to the world around but was, rather, emotionally and ontologically porous, open to the spiritual realm: an openness that was often expressed in fits of weeping. Spong also experiences the world around her in a sensorial, yet casual way–though without the gravity of religion. Her hands explore a stone wall and caress the curves of wrought iron fences. She writes:

I recently developed a desire to lick things, things like concrete, stone, architectural decorations…

A doctor put this down to re-experiencing the stage when children put everything in their mouths, that period before the tongue can speak, before words get in between.

Linking to Spong’s work is a Flemish stained-glass window from the late 15th century, depicting the Virgin Mary as ‘Woman of the Apocalypse’. She is set against stylised

sun rays with the moon at her feet; ‘the sun for her mantle, the moon under her feet.’ (Apocalypse of St John 12:1). This work operated as an icon—an item for prayer and contemplation—and demonstrates objects as loaded containers of emotion and portals of feeling. Acting as

an emotional conduit between the terrestrial and celestial spheres, it is an image in which spaces overlap. The sun’s rays radiate out in fiery tufts. Mary stands on the moon, yet this sits firmly on the earth that we can recognise from the delicate details of the etched foliage. The work, with its sparse graphic lines, also loosely links to later developments in certain modernist art where lines and forms operated as a means of accessing universal spiritual truth.

to unfurl IV (A6007550) 2017

pigment print, Tasmanian oak, acrylic paint, Perspex, grey enamel diabond, 3 panels

180 x 80 x 6 cm each

Courtesy of the artist and Kalli Rolfe Contemporary Art, Melbourne

Nik Pantazopoulos brings intimacy into a pictorial realm

that crosses abstract-expressionism, performance and an exploration of a formalist tradition. The work is an action captured: a process of the unfurling of his bedsheet into psychological environmental forms. Produced in the time of the same-sex marriage postal vote in Australia, the backdrop of this work is the personal wrestling with a relationship, and the pressure of having the private made public. The sheets in this work undergo a process of, ‘unmaking; twisting, knotting, wrestling, forming, reforming, pouring, holding, releasing, open to the wind.’ It is an object containing the body’s remnants—the heated imprint of limbs and sweat— transformed into abstract shapes that have looser, wider and unspecified connotations, hinting at something universal and beyond. Also inherent to this work is the queering of a heroic hetero-normative gesture: the ‘gesture’ of expressive individualistic masculinity (think Jackson Pollock et al.) is fractured through its formation from a bedsheet that contains not just the gesture of the artist’s body but of another as well.

Emotions are orientations towards things, towards objects, towards people. Art encourages feelings: it is predicated on a viewer encountering cognitively and sensorially, an artwork towards which they may develop a position. In this way, art is implicit in the passing around of feeling. The works in this exhibition—whether concerned with voice, actions of objectness—are spaces, enclosed in artwork form, where the complexity of emotion arises. They speak from different positions but threaded through is a concern for how emotion operates in the world, nudging towards a softer, more complex and compassionate weaving of feelings through our lives.