Dying, a conversation worth living—

Travis Curtin

We discovered that grief was much more than just despair. We found grief contained many things – happiness, empathy, commonality, sorrow, fury, joy, forgiveness, combativeness, gratitude, awe, and even a certain peace. For us, grief became an attitude, a belief system, a doctrine – a conscious inhabiting of our vulnerable selves, protected and enriched by the absence of the one we loved and that we lost.

[. . .] in time, there is a way, not out of grief, but deep within it.

Nick Cave, The red hand files 95 (May 2020),

http://www.theredhandfiles.com/create-meaning-through-devastation

The immediacy of loss is one of the most difficult experiences to articulate in words. One foot on the ground, one foot in the water tests what an art exhibition can do to express the complexities and mysteries of the emotional experiences surrounding death and loss that reverberate through time.

In his 2008 book, Art and death, Chris Townsend suggests that rather than coming to terms with our own death, ‘it is the deaths of others that lay claim to us, as witnesses’. Townsend proposes that ‘there is a degree to which, as Jonathan Strauss argues, death is “a fiction derived from other experiences of loss, most significantly that of other people”’. As quoted by Townsend, Strauss has stated that ‘my death is an awareness of myself that I can only have through the idea of others who will survive it, and it is in this sense a blind spot in my self-knowledge’.1

My personal experience of loss has been an overwhelming sense of present–absence. As Townsend and Strauss identify, our own experience of death is intangible. Like many of us, I have a second- hand experience of death. My partner Anna was diagnosed with stage-four cancer and lived with it for four and a half years until she finally could not. I was with her for the last three weeks of her life, between Warrnambool Hospital and the Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, where she passed away on 31 May 2015.

Most vivid in my memory is the shock at just how quickly she slipped from being her beautiful cognisant self to being presently absent. Her body lying on the hospital bed in front of me. But not there at all. A vessel for life, finally no longer capable of supporting it. A container emptied of its essence.

1. Chris Townsend, Art and death (London and New York: IB Tauris & Co. Ltd, 2008), 2.

I was asleep in the next room when Anna died. When I entered the room, I could no longer feel her in it. She was absent. Her life had finished. Nothing could have prepared me for the finality of that moment. Nothing could have prepared me for the sense of absence when it was all over, despite being acutely aware of the drawn-out process of her body shutting down over the course of her final weeks. Anna desperately wanted to live to the end, right up until her last shallow rattling breath, drawn as Nick Drake’s album Five leaves left (1969) played softly through the speaker in a corner of the room. When I entered, the song ‘Saturday sun’ was playing. I think it was around 5:00 am. I’m foggy on the details. Being at the hospital no longer made sense. I was no longer needed there. Together with her family I packed up Anna’s things and drove home. Home, another vessel emptied of meaning and the significance it once held when we were both in the world to share it. Layers and layers of things to grieve for. Layers and layers of things to let go of or hold on to.

Anna had a small family funeral and burial at Lilydale Cemetery, northeast of Melbourne, where her grandparents are also buried. This was followed by a large memorial service in Williamstown by the water. That week I felt numb amidst a blur of activity while preparations were made. Part of the process involved preparing Anna’s body for burial by washing and dressing her with her sister, brother, mother and father. Laying her in her coffin. These were Anna’s wishes. She had wanted her family to put her in her coffin. Until this moment I hadn’t used the word ‘goodbye’. I had completely avoided it. Instead, whenever I left the room at the hospital I would say ‘see you soon’. Perhaps fearing it would be the last time. Now it was the last time.

Death has been a source of inspiration that has stimulated the production of art, music and the word (sung, spoken and written) throughout history. It is a vast and diverse subject – too vast and diverse to cover here in any honest way. There are countless examples of cultural material across time that have been influenced and inspired by the subject of mortality. In his book, Very little . . . almost nothing, Simon Critchley suggests that ‘death is radically resistant to the order of representation. Representations of death are misrepresentations, or rather representations of an absence’.2 We may never truly know or articulate the experience of our own death, but perhaps we can better learn to live with death through the experiences of others and the myriad ways the living respond to death, through acts of mourning and grief. One foot on the ground, one foot in the water shifts the focus from skulls, skeletons and memento mori (reminders of inevitability) towards lived experiences that have a lasting legacy. It offers experiences that stimulate broader discussion around death and dying; experiences that bring the living together.

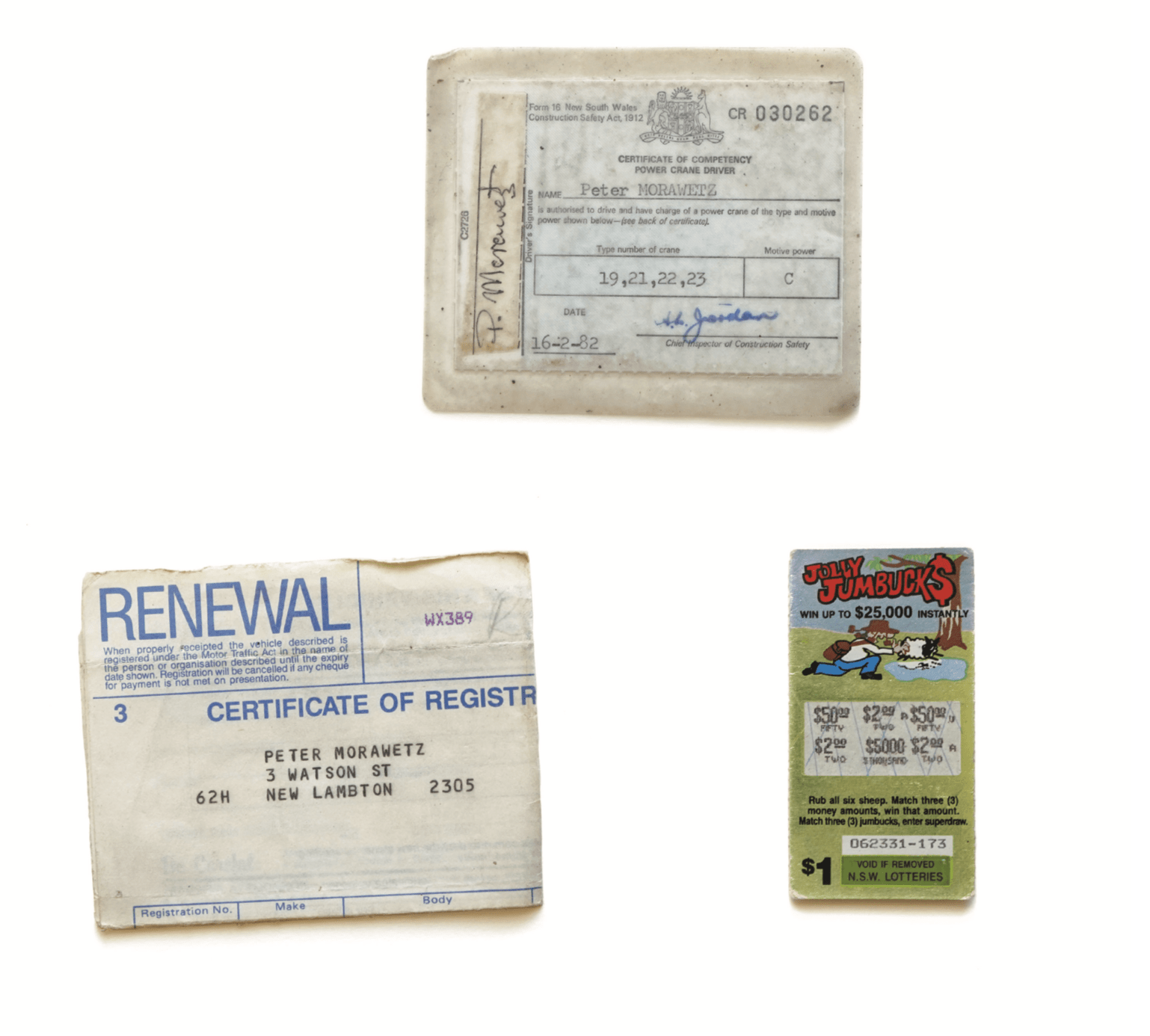

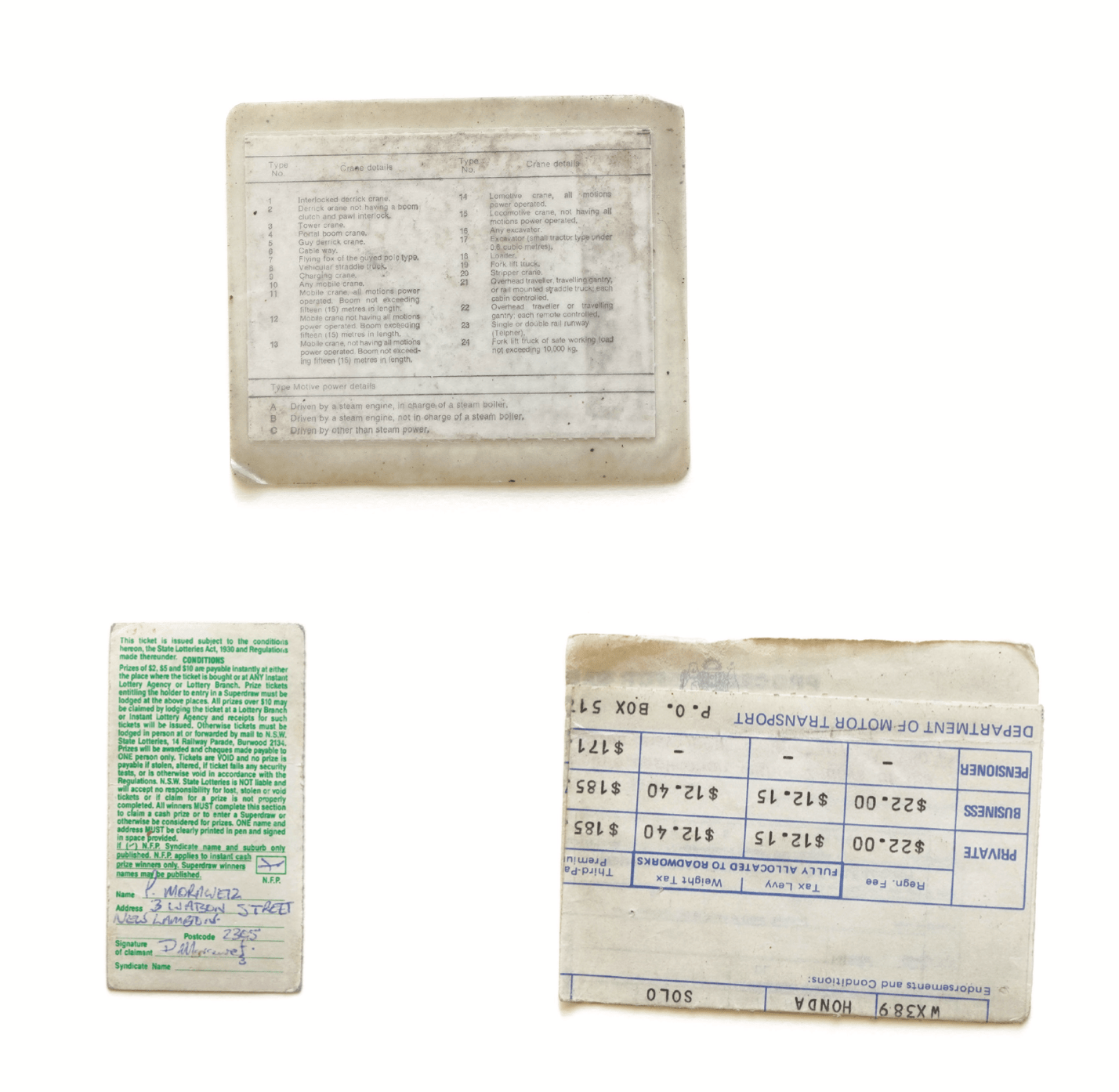

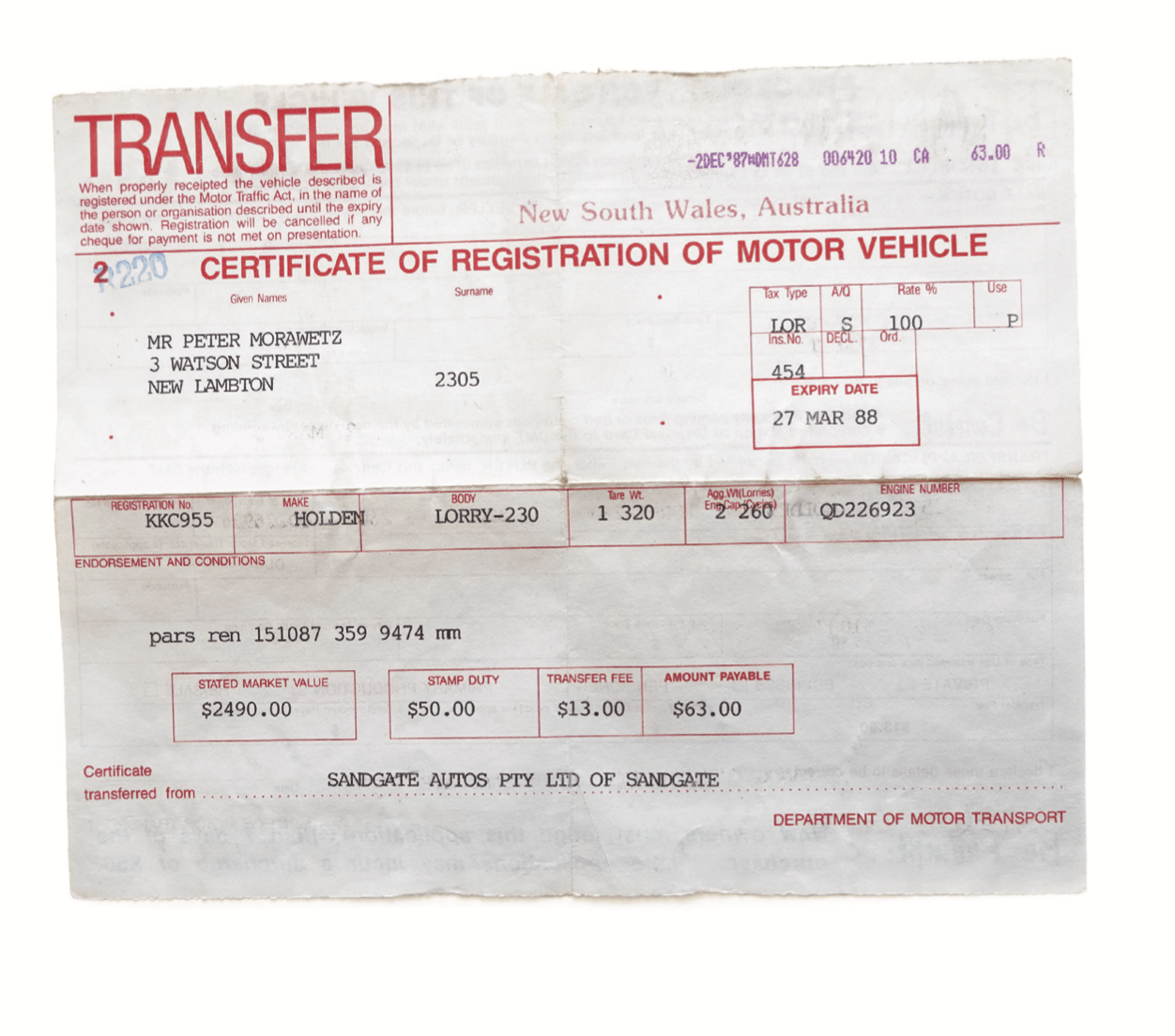

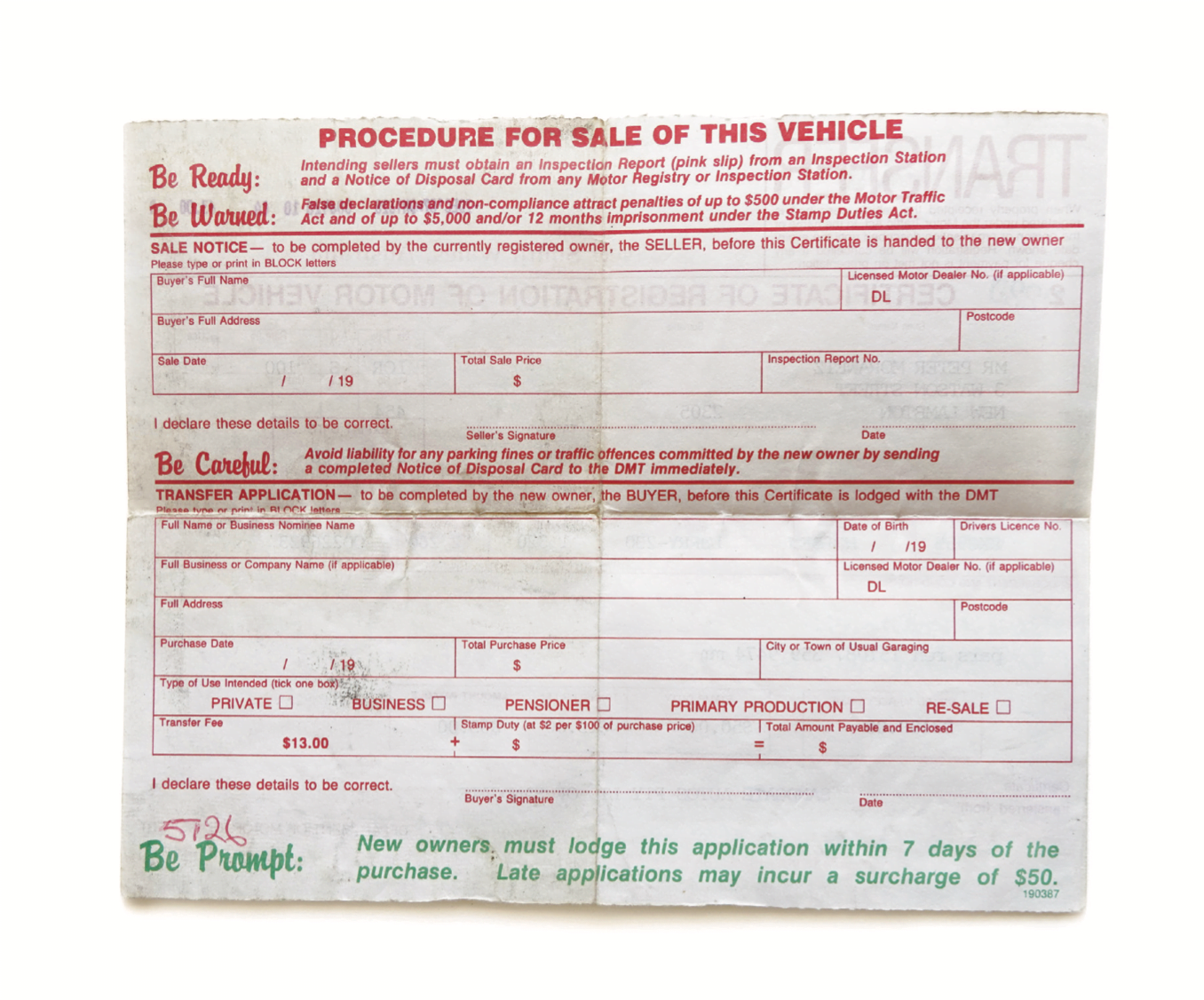

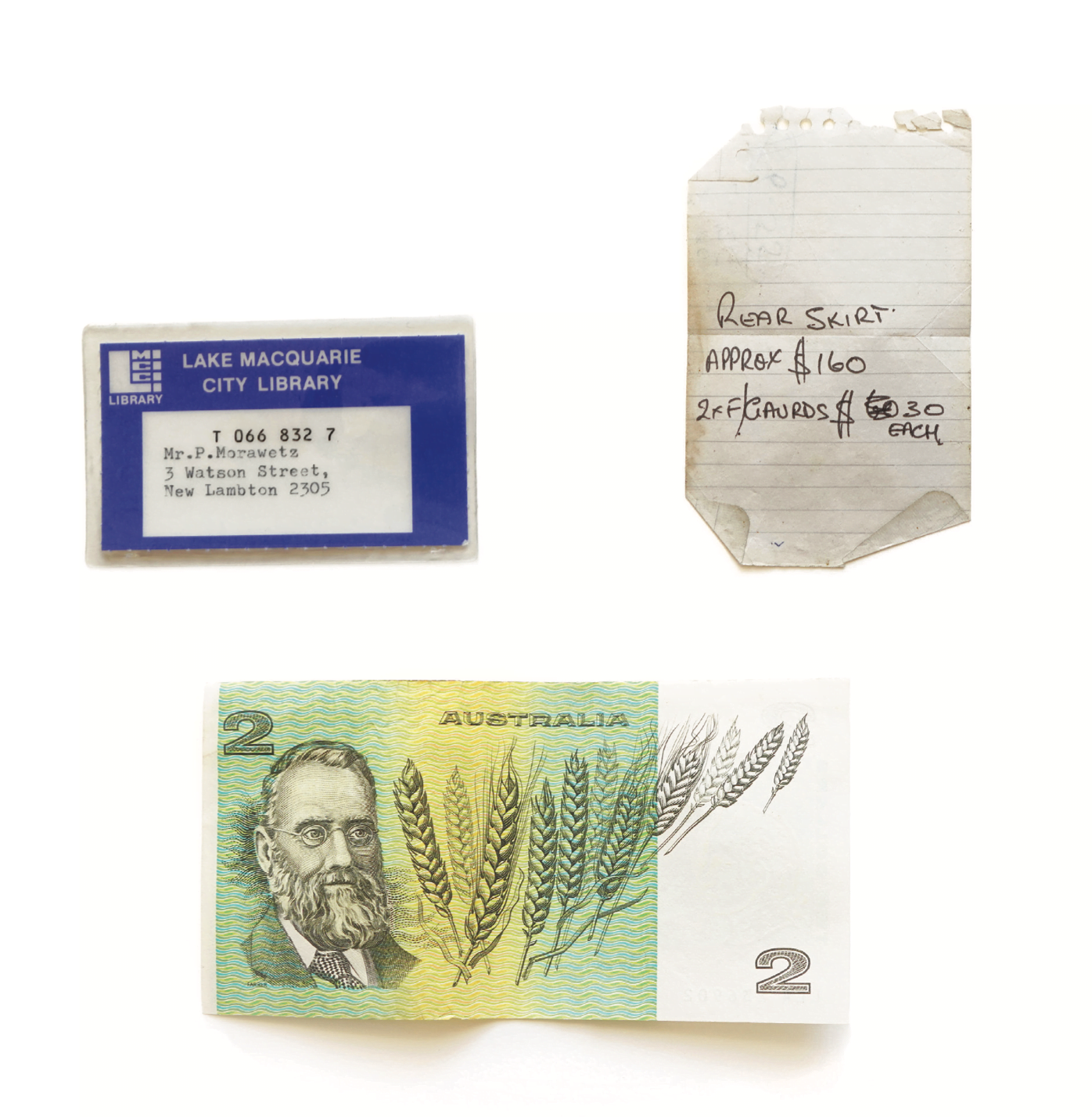

Throughout the exhibition, singular and repeated forms reinforce the reality of death as both an individual and universal experience. Sara Morawetz’s March 17 (2020) presents an unconventional memorial dedicated to Peter Morawetz, who was tragically killed in a motorcycle accident 32 years ago while in the process of selling his motorbike to pay to legally become her father. Morawetz’s artist’s book catalogues the objects that were in Peter Morawetz’s wallet at the time of his passing. The book documents her deeply personal experience of loss, the act of making itself a form of grieving. As Morawetz identifies, the wallet’s contents are the ‘unremarkable ephemera of a 28-year-old man – made invaluable by his absence’. March 17 captures an intangible essence beyond physical presence.

2. Simon Critchley, Very little . . . almost nothing: death, philosophy, literature (London and New York: Routledge, 2004), 31.

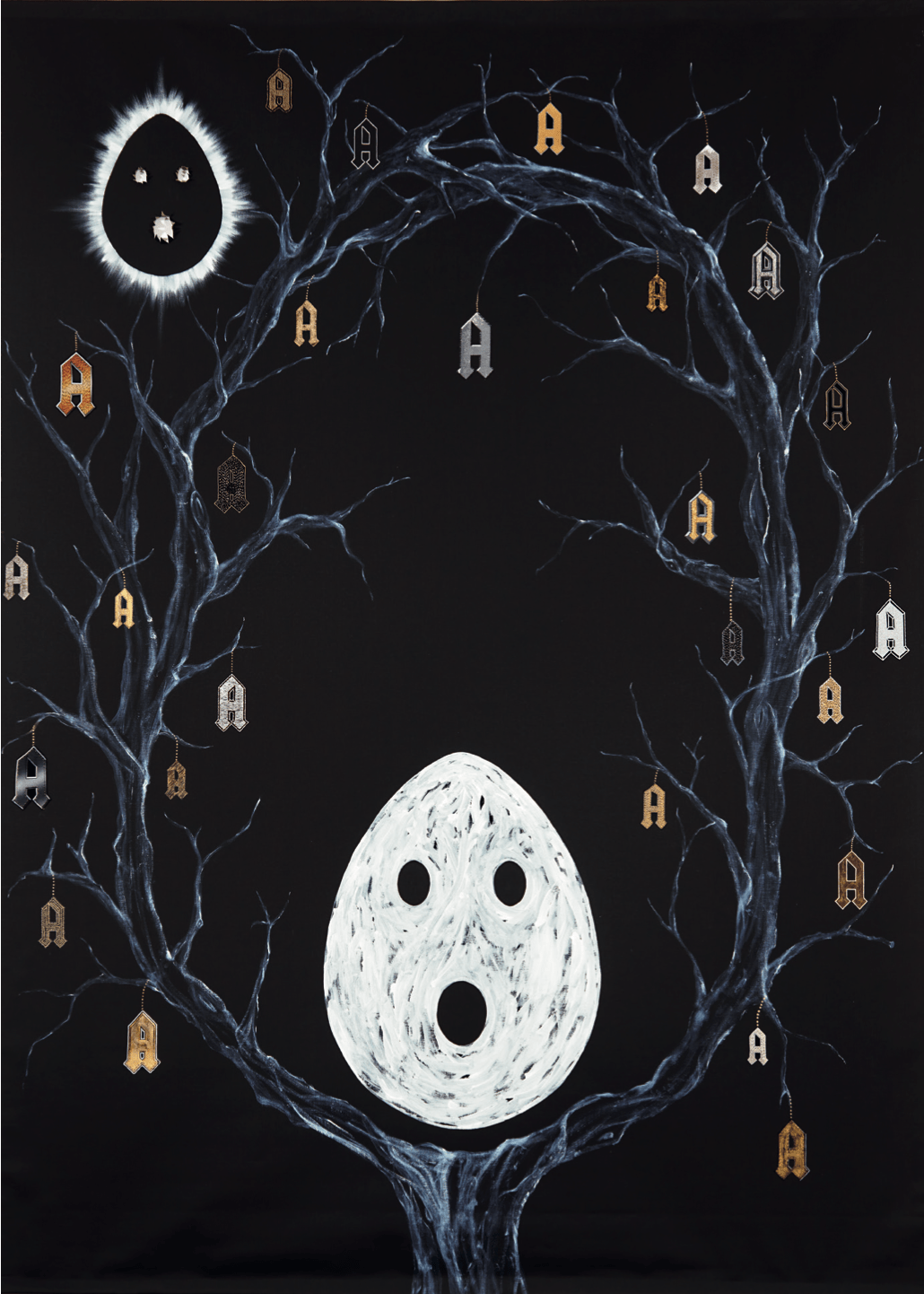

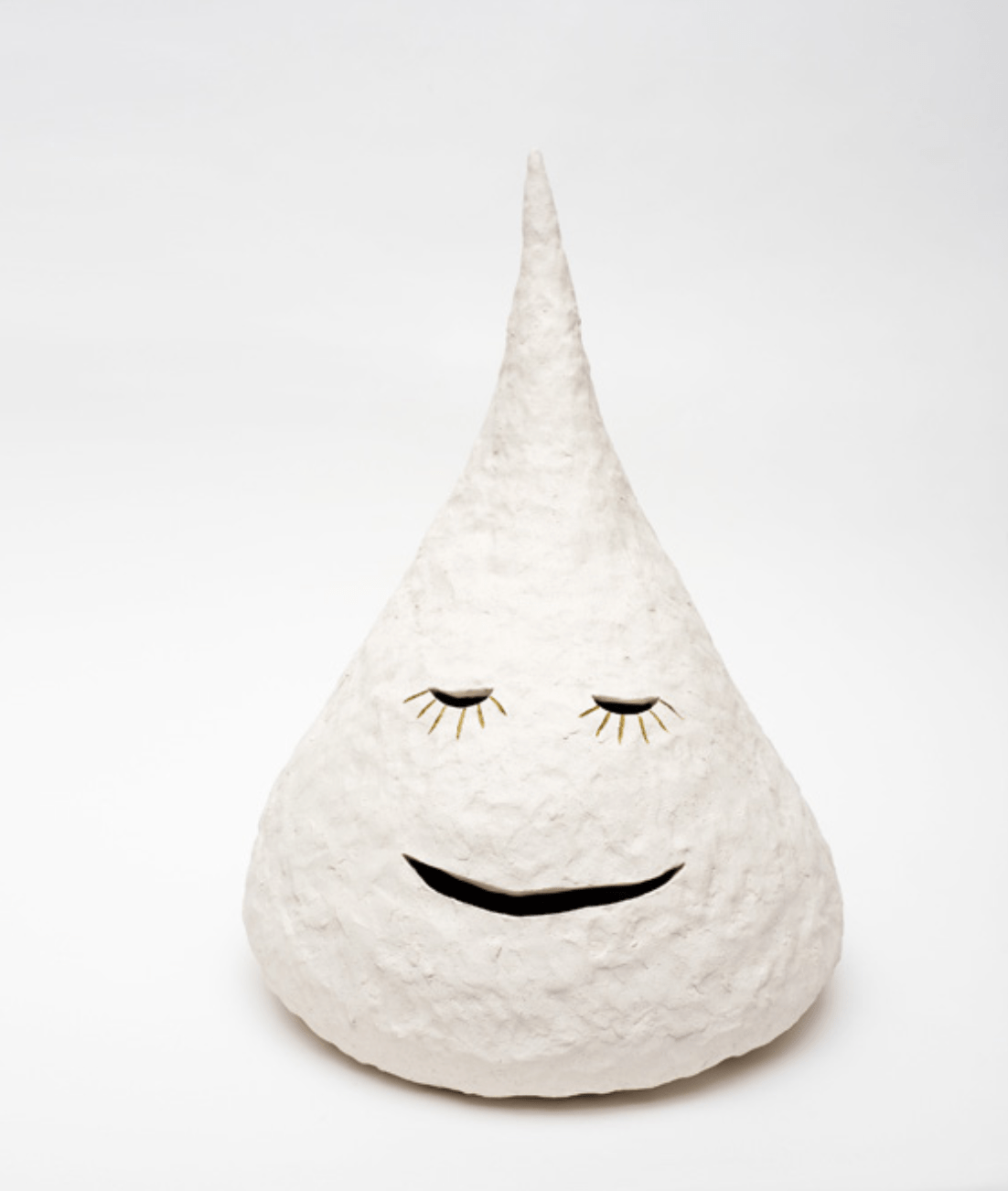

Nell’s Mother of the Dry Tree and With things being as they are . . . (both 2017) have also been created in the context of grief following the artist’s loss of her son, Lucky, due to stillbirth in 2012. These works feature recurring images of large and small egg-shaped forms, ceramic sprites and glass ghosts, open-mouthed and open-eyed, suggesting a state of shock. Throughout Nell’s installation, mother and child are disconnected from one another, but close nonetheless.

Referring to these works, Nell has stated:

In my painting the mother and the child are separated, as if calling to each other. I had a stillborn baby boy [. . .] and it was, goes without saying, incredibly traumatic and changed my life irrevocably and it really changed my art practice too. I made

a commitment to make art about my life, a long time ago and now this little spirit’s very much in my work [. . .]. My arms ached afterwards and so I wanted to make these little vessels or little spirits that I could hold in my arms.3

With this body of work, Nell shares with the viewer the little sprite who ‘passed through’, who will forever dwell in her heart and mind and perhaps continue to reappear at times in her works of art.

These personal expressions of loss contrast with the repeated forms of Richard Lewer’s Crucifixes (2018) and Catherine Bell’s Final resting place (2018–20). Both these works use repetition to depict the interlinking of discrete individual experiences through our shared humanity.

Mother of the Dry Tree 2017

3. Nell, ‘Love and music,’ interview by Rachel Storey, Art makers, ABC Arts, 22 June, 2017, video, 5:56.

Lewer has previously referred to the symbolic ambiguity of the cruciform, stating ‘the crucifix, to me, is an unmistakeable visual representation of absolute vulnerability, with its twisted human form evidence of extreme physical suffering, whereas for others,

it offers a beacon of hope, as with death there is always the opportunity to transcend this life to a better place’.4 Lewer’s work embodies this ambiguity and locates it in the viewer’s reading of the work, questioning the universality of iconography associated with death and dying. Similarly, Mabel Juli’s Garnkiny Ngarranggarni (2020) in proximity to Nell’s A cross (2017), draws into question Eurocentric readings of the cruciform, reminding us that iconography is a cultural construct and that forms are capable of embodying a multitude of meanings.

The repetition in Lewer’s 52 crucifixes contrasts with his painting As a bald man, I miss going to the barber (2019), a singular representation that draws our attention to the small ways we endure and survive embodied experiences of loss over the course of our lives.

The relationship between the individual and the universal significance of mortality resonates in Patrick Freddy Puruntatameri’s carvings, Purukuparli (2020) and Waiyai (2020), and their roles in the Purukuparli story recounted in this catalogue by Pedro Wonaeamirri. The Purukuparli story explains the origins of mortality from a Tiwi perspective in the death of Purukuparli and Waiyai’s son Jinani, during Parlingarri (olden times). In his second essay, Wonaeamirri outlines the significance of Pukumani and the Pukumani ceremony in Tiwi culture.

I AM Passing through 2017 23

4. Richard Lewer, ‘There is light and dark in us all’, (Adelaide: Hugo Michell Gallery, 2018), https://www.hugomichellgallery.com/richard-lewer-there-is- light-and-dark-in-us-all.

Crucifixes (detail) 2018

In the exhibition, tutini (Pukumani poles) carved by Patrick Freddy Puruntatameri and animated with jilamara (designs) by Timothy Cook, are exhibited alongside Cook’s iconic representations of Kulama, which refer to the men’s initiation ceremony and annual celebration of life, as well as Japarra (the moon man) and his role in the Purukuparli story, exemplifying the inseparable link between life and death in Tiwi culture.

In late 2019, I visited Timothy Cook, Patrick Freddy Puruntatameri and Pedro Wonaeamirri in Milikapiti on Melville Island. On the second last day of my stay an old man passed away. Timothy and I had been talking about Jinani the day before and he said to me, ‘That old man died. Jinani died. Then we all go follow like that’. The Purukuparli story has been told countless times, by different people in different ways. The death of Jinani, the first in Tiwi culture, has resonated for generations of Tiwi and is a unifying force that brings people together through the universal experience of dying – ‘we all go follow like that’.

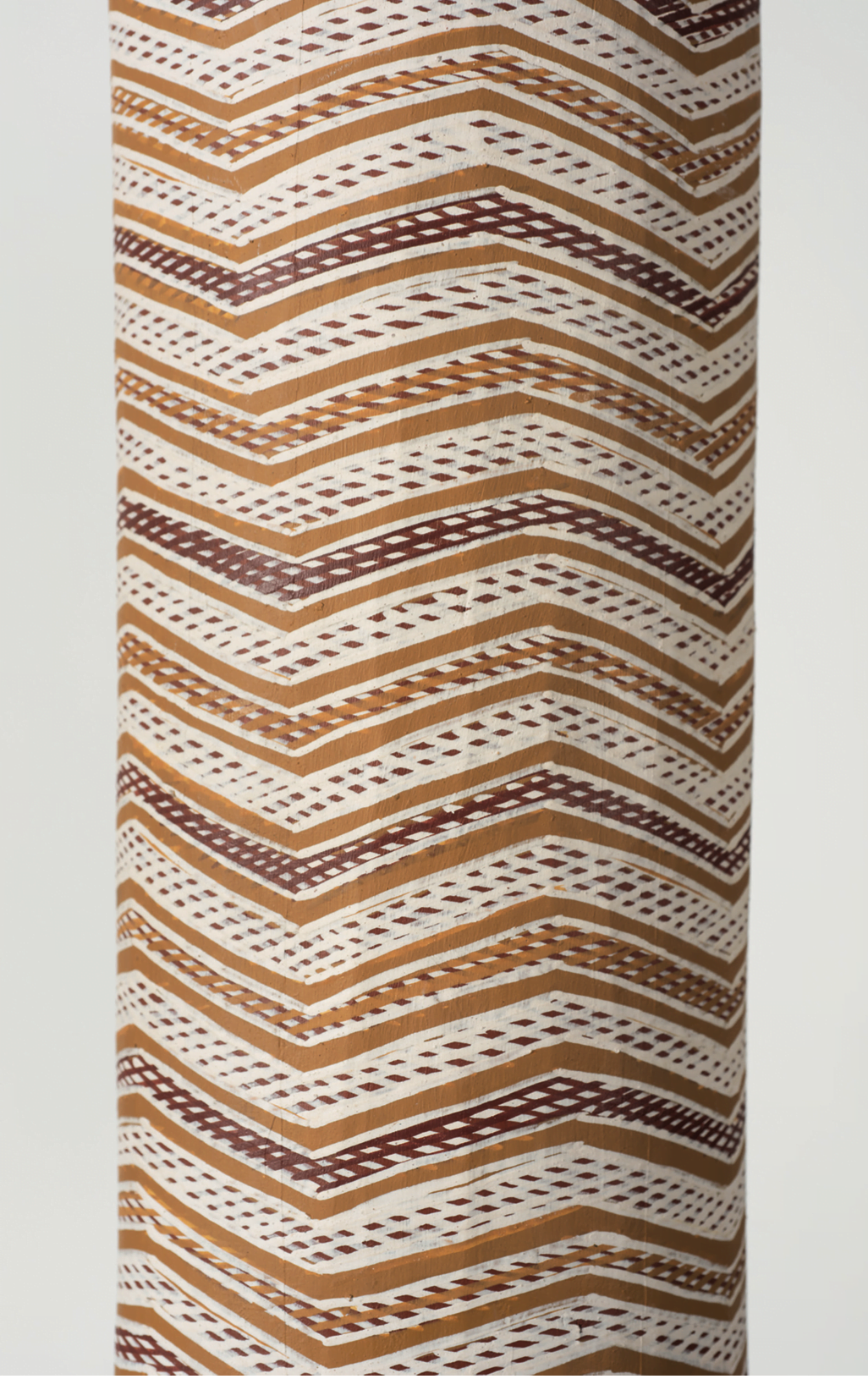

Throughout the exhibition, organic materials encourage us to consider states of permanence, impermanence and transitional phases in-between. Wood and natural earth pigments feature prominently, as in Timothy Cook and Patrick Freddy Puruntatameri’s tutini (Pukumani poles), Patrick Freddy Puruntatameri’s carvings, Purukuparli and Waiyai, Mabel Juli’s Garnkiny Ngarranggarni in natural earth pigments and charcoal – the residual carbon of burnt wood and other organic matter – and Nawurapu Wunuŋmurra’s _larrakitj (memorial poles) Garrapara (2007 and 2012) and Mokuy (2012). In ceremonial contexts, _larrakitj in Yolŋu culture and tutini (Pukumani poles) in Tiwi culture are left to deteriorate in the elements (sun, wind, rain and saltwater) following the conclusion of the respective ceremonies that perform the function of seeing the spirit of the deceased safely on its way.

Just as the _larrakitj returns to the earth, decomposing in the elements, Wunuŋmurra’s _larrakitj represent the cyclical journey of the spirit from a Yolŋu perspective. The miny’tji (sacred clan designs) on Wunuŋmurra’s _larrakitj represent the sea at Garrapara, a Dhalwaŋu clan estate, coastal headland and bay area within Blue Mud Bay, in Northeast Arnhem Land. The wavy design indicates a Yirritja moiety body of saltwater in Blue Mud Bay called Muŋurru. It is here that the ‘water (soul) transmogrifies to vapour, entering the “pregnant” waŋupini (storm clouds) which carry the life-giving freshwater back to the start of the cycle’.5

As Will Stubbs identifies in his essay ‘Water, kinship and the cycle of life’ in L_ arrakitj: Kerry Stokes Collection:

Water is paramount because each person has the water from which they have sprung, within [. . .] The purpose of many Yolŋu ceremonies is to guide the spirit through the cycle and through the water – to return the spirit back to the reservoir of origin. There is a sense that the spirit doesn’t want to leave. The body has components: the spirit, the flesh and the bones. The flesh melts away shortly after death; the bones are geologic, and must return to the land through the agency of _larrakitj. That leaves the eternal spirit, which must find its way through the waters, back to the reservoir of the communal soul. That resides in sacred springs or rivers, and it must be assisted in that progress, guided by rituals and music, patterns and dancing.’6

French & Mottershead Grey Granular Fist 2017

Background:

Richard Lewer

As a bald man, I miss going to the barber 2019

Installation view, La Trobe Art Institute, 2020 Photograph: Ian Hill

5. Nawurapu Wunuŋmurra, Garrapara, artwork documentation (Yirrkala: Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre, 2012).

6. Will Stubbs, ‘Water, kinship and the cycle of life’ in Larrakitj: Kerry Stokes Collection, ed. Anne Marie Brody (West Perth: Australian Capital Equity, 2011), 39.

Ephemeral materials also feature in Catherine Bell’s Final resting place (2018–20), consisting of 100 vessels crafted from biodegradable floral foam by participants in her ‘Facing Death Creatively’ workshops. The workshops provide a forum for public mourning through, as Bell states, bringing the living together to use ‘ephemeral materials to think about impermanence’. They are a catalyst for discussing mortality and the participants’ final resting places.

The act of carving is a reductive process. The creation of a new form by rubbing away or removing layers provides a gentle metaphor for loss and letting go, a change in state or shedding of form. Bell’s choice of biodegradable floral foam reflects her interest in processes of decomposition and the return of materials to natural elements: earth, water and gas. These vessels also correspond to our corporeal existence and the body as a ‘carrier’. Bell links their functional form to the way the human body holds water. The floral foam holds water to sustain life for flowers ‘yet is paradoxically the grave to those flowers’.7

Nell also incorporates organic materials in With things being as they are . . . (2017). Japanese igusa tatami mats woven from soft rush straw, chicken skin, eel skin and stingray skin are all former living things, repurposed and given life in another form.

French & Mottershead’s Grey Granular Fist (2017), from the series Afterlife, presents an opportunity ‘to experience the afterlife of your body’. The work makes exhibition visitors acutely aware of the organic materiality of our own bodies, introducing the notion of the life cycle and the sometimes uncomfortable alliance between life and death. Sound inhabits the liminal space in-between tangible and intangible experiences. Here it is grounded in the embodied experience of sitting in a wooden chair where the materiality of the listener’s body (their physical weight) triggers the audio. Andrew Mottershead has commented that, ‘the [ Afterlife] series stems from a combination of personal fear connected to dying alone and not being found, and also a curiosity about the science of decomposition and decay [. . .] It’s all about the life that occurs after that last breath, about the process of transformation and renewal’.8

7. Catherine Bell, ‘Facing Death Creatively’ (La Trobe University Creative Arts, Visual Arts and Law School, 7 October, 2020), online workshop.

8. Hannah Reich, ‘Dark Mofo: Festival-goers experience death, decay and degloving on River Derwent in audio work “Waterborne,”‘ABC Arts, 23 June, 2018.

Michael Needham’s Monument to Muther [sic] (2020) evokes a sense of permanence through its weighty cast-iron bulk and looming 3.3 metre height. The exaggerated degree of ornamentation for an ambiguous mourned subject provides a layer of sardonic humour, and, as Needham states, the work overplays ‘formal posturing as a means of questioning implicit and often justifiably guarded sentimentality around loss’. In this context, Needham’s signature discarded plastic cemetery flowers offer further irony, as flowers provide an earthly reminder of the beauty and impermanent nature of life, meaning that is undermined by their plasticity and permanence. Nonetheless they imply that an offering, an embodied grief process, has taken place.

The monument elicits an uncomfortable presence in the Australian landscape, an intentionally jarring interplay between the sacred and the profane. This is further enhanced by the strangeness of the landscape Needham created in the internal courtyard of La Trobe Art Institute for the first iteration of the exhibition. The monument installed on a bed of sandy earth littered with twigs and scatterings of casuarina needles and seedpods that remind us of the life cycle; former carriers of life are now discarded vessels, left to decompose on the surface of the earth.

Monument to Muther [sic] 2020

Installation view, La Trobe Art Institute, 2020

Photograph: Ian Hill

Mortality is imposed on all of us eventually. One foot on the ground, one foot in the water ultimately tells a story of finality and legacy through art as a form of ongoing life beyond life itself. In death, the body continues to merge with the life cycles of other humans, living things and processes. The cycle continues and we are undeniably a part of ‘life that exists beyond life itself’.9 The essence of a person, whatever name you give it, continues to resonate in present-absence.

Art and other forms of cultural expression play a major role in the way we respond to death. There is solace to be found in art, music, words and ‘deep within grief’, as Nick Cave writes in response to questions about finding meaning from tragic loss.10 Art provides a means of connecting with one another in order to make sense of our own experiences. French philosopher Gilles Deleuze writes that, ‘In art, and in painting as in music, it is not a matter of reproducing or inventing forms, but of capturing forces [. . .] Paul Klee’s famous formula – “Not to render the visible, but to render visible”’.11

The works presented together for the first time in this exhibition offer a unique group of intercultural perspectives on death, dying, loss and grief. It is my hope that One foot on the ground, one foot in the water echoes and reverberates in a poetic way for its viewers in much the same way that someone remains with us as a series of traces in memory or echoes in objects that carry the mark of their being after they are gone.

Travis Curtin, Curator.

March 17 (detail) 2020

9. French & Mottershead, French & Mottershead, 2020, http://frenchmottershead.com/works/afterlife.

10. Nick Cave, The red hand files 95 (May 2020), http://www.theredhandfiles. com/create-meaning-through-devastation.

11. Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon: the logic of sensation (London and New York: Continuum, 2003), 56.

March 17 (details) 2020