Creative Acts in an Epoch of Environmental Change—

Jessica Bridgfoot

There are fewer more sobering images than that of a bleached coral reef or the ‘Bermuda Triangle’ of plastic in the Atlantic Ocean. The state of the planet has led to the suggestion of a new geological period entitled the Anthropocene,1 a period that defines human activity as the dominant influence on the Earth’s ecosystems. Beginning in the 1950s with the ‘great acceleration’ – an era of nuclear bomb tests, population boom and disposable plastics – the Anthropocene is an epoch characterised by climate change, mass production and resource wars.

Historically, artists have played an important role in reflecting and engaging with environmental concerns. In the British colonial settlements of the 18th and 19th centuries, artists were commissioned to create topographical renderings of the newfound lands, depicting – sometimes unwittingly – the clearing and decimation of the environment, while at other times glossing over the colonial project with idealised pastoral landscapes. The emergence of photography offered another medium through which to trace human influence on the landscape and by the late 20th century, the Land Art movement emerged, with key proponent Robert Smithson. Joseph Beuys also made meaningful interventions on ‘damaged’ land to suggest rejuvenation and rebirth. Beuys’ 7000 Oaks project began in 1982 in Kassel, Germany and later spread to other cities around the world. The project, which took five years to complete, enlisted community members to plant oak trees in a gesture towards green urban renewal and demonstrated the power of creative community activism to initiate real change.

Art provides a seductive vehicle by which to highlight environmental issues as it utilises the aesthetic, the physical and the emotional. In Craftivism. Dissident Objects and Subversive Forms, artists Raquel Ormella, Kate Rohde, James Tylor and Erub Arts present works that employ traditional craft techniques to engage with the history and geography of the natural world in a globalised 21st century environment.

Raquel Ormella has maintained a practice as both a documenter and an advocate of environmental activist movements, immortalising political slogans and subversive quips in thread. In the wake of feminist artists before her, including Judy Chicago, Louise Bourgeois and Tracey Emin, Ormella uses needlework techniques from centuries of domestic work and firmly places it in the midst of contemporary art practice.

1. The Anthropocene was first described by Nobel Prize- winning atmospheric chemist Paul Cruzen in 2000.

Raquel Ormella. Blockade in my studio for the Pilliga Forest #1 (detail) 2018. © the artist, courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane.

Ormella is interested in the language and materials of grassroots political organisations and has also produced substantial bodies of work focussing on the campaigns of the Wilderness Society. The Blockade in my studio for the Pilliga Forest series 2018, references the recent protests of community collective Knitting Nannas Against Gas (KNAG). The women of KNAG gather in public spaces and at protest sites; they are women, farmers, retired teachers, mothers and grandmothers. They talk, plan and,

crucially, they knit. They protest peacefully, their knitting enabling them to participate in acts of non-violent direct action. As they state, ‘We want to leave this land better than we found it … We sit, knit, plot, have a yarn and a cuppa and bear witness to those who try to rape our land and divide our communities.’2 They are the modern Australian Les Tricoteuses, a group of social revolutionaries who sat and knitted at the guillotine while observing the mass executions of aristocrats during the French Revolution.

2. Elizabeth Farrelly, ‘KNAG Power: Knitting Nannas on the March against Fracking Polluters’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 September 2017, Accessed 30 July 2018, https://www.smh. com.au/opinion/knag-power-knitting-nanas-on-the-march- against-fracking-polluters-20170831-gy824u.html.

In the vein of political craft movements, the labour of Ormella’s creative process is in itself an act of care and reparation. With a topographical, textured layering of sandy browns, greens and orange, Blockade in my studio for the Pilliga Forest #1 announces ‘KAMILAROI LAND/SAVE THE PILLIGA FOREST’. The time invested and the intimacy of Ormella’s thread work are almost absurd counterpoints to the 24-hour news cycle – consider the immediate devastation that one email from a remote high-rise office building could cause for a thousand-year-old ecosystem.

Materiality is symbolic in Ormella’s works, which employ a mix of high and low materials

and repurposed garments. In this series, Ormella embroiders cotton thread on a used ‘hi-vis’ work shirt, the everyday uniform for more than 200,000 Australians working in the mining industry.3 Perhaps Ormella is acknowledging that this environmental debate is not clearly defined and nor are the winners and losers. Like KNAG – who provide cups of tea to the corporates against whom they protest – Ormella leads by example; her message is inclusive, not divisive. Playful, seductive and endearing, Ormella’s work filters the worlds of craft and political protest through the lens of second-wave feminism and conceptual art.

3. Penny Vandenbroek, ‘Employment by Industry Statistics: A Quick Guide’, Parliament of Australia, Accessed 18 August 2018, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_ Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1718/Quick_ Guides/EmployIndustry.

Nancy Naawi. Ghost net vessel 2016. © the artist, courtesy the artist and Erub Arts. Photo: Lynnette Griffiths.

Further critique on the environmental impacts

of industry are offered in Erub Arts collective’s Ghost net vessels 2015–18. GhostNets Australia, an alliance of coastal Indigenous communities from Australia’s top end, including Erub Arts, tells the story of an Indonesian fisherman whose trawl net is severed from his boat when caught on sharp coral. The net – made from non-biodegradable plastics – joins thousands of other ‘ghost nets’ that haunt the ocean, beholden to the tides, tangling their inhabitants and killing hundreds of thousands of sea creatures. Weeks later, the fisherman’s net washes up on the western shores of the Torres Strait, entangling a sea turtle that struggles for its life. An Indigenous ranger saves the turtle and collects the net for his Aunty, who skilfully weaves the net into an artwork.4

Erub Arts hails from a remote location of the Torres Strait, at the most northerly point of Australia. Ghost nets are a shared concern for coastal Indigenous arts communities. Their craft practices seek to highlight the damage that rogue nets left by fishing industries are inflicting on Australia’s marine life. It is estimated that up to 640,000 tonnes of ‘ghost gear’ is left in oceans each year and can remain for up to 600 years, killing thousands of sea animals annually, with turtles being the most vulnerable.5

4. GhostNets Australia, Accessed 30 July 2018, www.ghostnets.com.au.

5. Michael Walsh, ‘Ghost Gear Killing Hundreds of Thousands of Whales, Seals, Turtles and Birds’, ABC News, 5 June 2017, Accessed 30 July 2018, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-06 -05/ghost-fishing-nets-killing-marine-animals/8591020

Photos: Brooke Holm.

Erub Arts’ woven vessels are a contemporary reimagining of the ancient craft of weaving – using the most unnatural materials. There is poetry in the life cycle of the ghost net, a sense of redemption for the material in its artistic reincarnation. The message cannot be mistaken, however, as for Erub Arts, this is a cruel labour of love and a defiant act of protest.

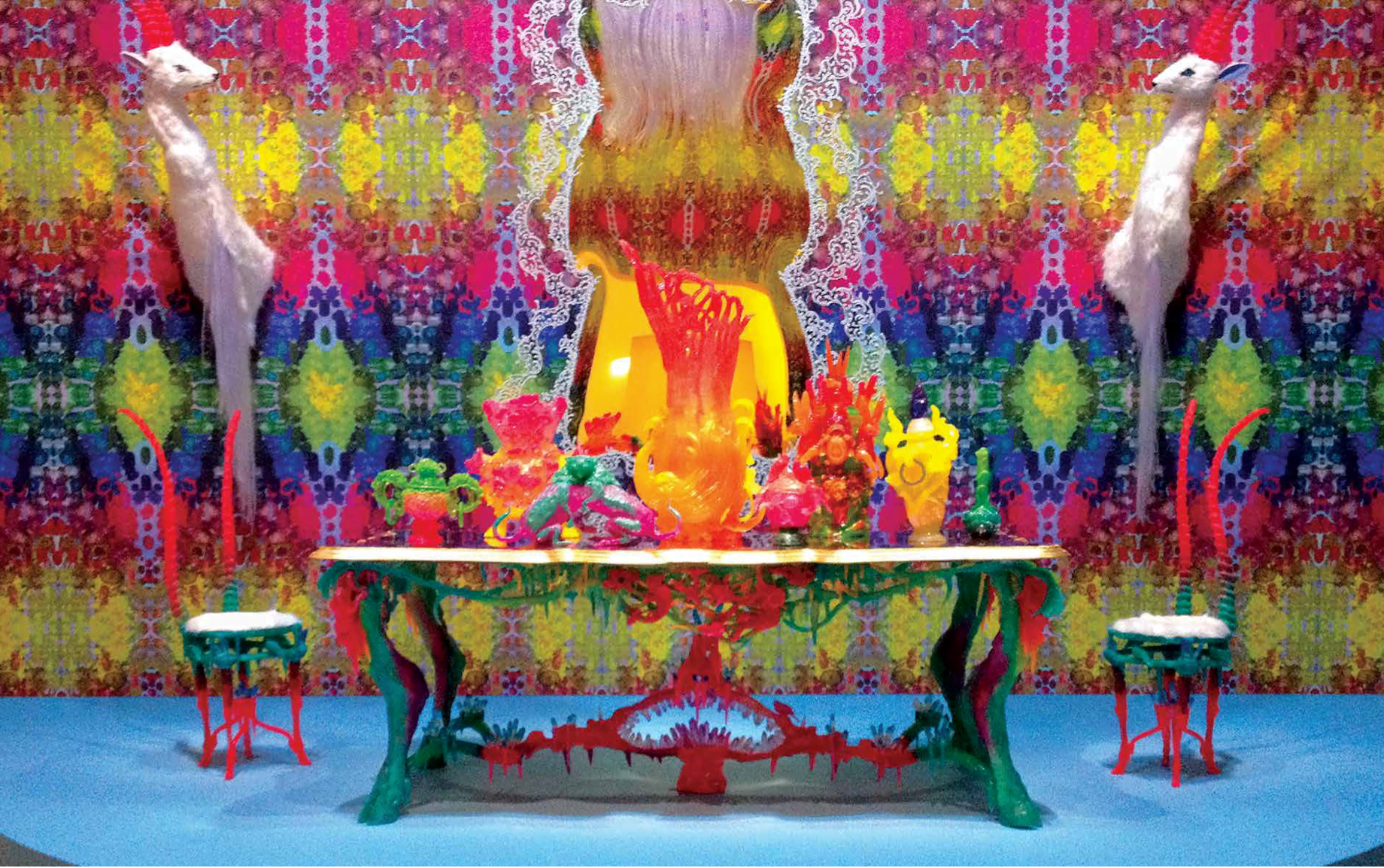

Relationships between the natural world and modern consumption are investigated by Kate Rohde in her 2018 site-specific ‘wunderkabinett’ at SAM. Made from synthetic fur, dyes, resin, paper and enamel, there is evidently nothing natural about Rohde’s installation. Citing an interest in the High Baroque and Rococo periods of opulence and excess, Rohde’s work employs a ‘more is more’ lurid artistry.

Photos: Brooke Holm.

Un-resettling (Animal net)

Un-resettling (A-frame hut)

Un-resettling (Native rat trap)

Un-resettling (Bird snare)

Gadla Purtultu (Fire stick), Warpoo (Bone chisels), Wadla (Tree climbing

sticks), Wunupi (Cooking tongs)

Wadni (Boomerang), Mullabakka (Broad bark shield), Midla (Spear thrower)

Tawiti (Grindstone), Mokani (Hafted stone axe), Bakkebakketti (Stone knife)

Pileyah (Grub hook), Kuya nguri (Fishing line)

James Tylor, Kaurna language group (Tarntanya Adelaide, SA). 2018 © the artist, courtesy the artist, Vivien Anderson Gallery, Melbourne and GAG Projects, Adelaide.

There is optimism in the craft of making at a time when the future is uncertain, a will to put the brakes on the ‘great acceleration’ and also to engage in constructive acts of reparation.

Historically, animals (and humans) died for the excess of empire. This extreme sacrifice is evident in the cochineal red created from millions of insects and used to dye red the coats of the British army, among many other things. It can also be seen in the toxic materials (including lead, arsenic, cobalt and mercury) used by craftspeople, which led to all sorts of nasty ailments – and to terms such as ‘as mad as a hatter’, which is derived from the mercury poisoning experienced by many milliners.

Within the work, Rohde employs a particularly toxic blue pigment, ramping up the artificial to invoke a hyperreal state of wonder. Illustrating her intent, Rohde recalls hearing a story of a woman who died after dancing the night away in an exquisite green dress, the colour of which had entranced both her and her company. The dress had been coloured with an arsenic-based dye, which leached into her skin and poisoned her.6

Amidst the beautifully lurid cacophony of colours, textures and foliage within the wunderkabinett, a unicorn appears in a repetitive wallpaper motif. The unicorn is of interest to the artist for its mythical power as a creature that can neutralise any poison with its horn. In Christian art, unicorns are depicted as angel-like creatures in an unsavoury world. Eastern mythologies incorporate the unicorn as a symbol of loss, which appears before a death. Rohde’s wunderkabinett could offer a beautiful, yet terrifying, foretaste of a toxic world where we might all walk on fake grass. In our relentless state of consumption, we are – in fact – poisoning ourselves.

A contemporary manifestation of the Victorian aesthetic is found in James Tylor’s hand-coloured photographic images. With a diverse ancestry including Nunga (Kaurna), Maori (Te Arawa) and European (English, Scottish, Irish, Dutch, Iberian and Norwegian), Tylor uses Victorian photographic techniques to unpack the topic of British colonisation in Australia and New Zealand.7

6. Conversation with Kate Rohde, July 2018.

7. Conversation with James Tylor, July 2018.

In the body of work Un-resettling 2018, Tylor presents a series of hand-crafted Indigenous Australian tools alongside a suite of staged photographs of newly created traditional dwellings, ovens and animal traps that were used by Australia’s first peoples before white settlement.

Tylor has begun a lifelong journey to learn ancient practices and cites a recent encounter with Bruce Pascoe’s revolutionary book Dark Emu 20148 in validating his quest to highlight traditional Indigenous Australian agriculture. Using traditional materials, Tylor creates throwing sticks, stone-head axes, boomerangs and other objects that were utilised for tens of thousands of years by Indigenous people living in harmony with the land. Many of the objects Tylor creates were traditionally used for trade between clans, highlighting First Nations peoples’ forms of currency and the values that were linked to function and sustainability. Indigenous knowledge systems, beliefs and practices were little-understood by the capitalist colonists, who took it upon themselves to ‘tame’ the land by imposing hard-hoofed animals, planting European crops and trees, and embarking on a ruthless quest for the resources (such as gold) on which they placed great value.

By mimicking Victorian daguerreotypes and the colonial lens, Tylor is effectively ‘filling in’ the record of an existence that was excised from history, that of Australia’s first peoples. Furthermore, Tylor’s installations resemble those of a museum; objects are mounted to the wall for inspection in a manner suggestive of Western ethnographic displays. In this sense, rather than highlight the differences between the cultures (Tylor cites this kind of cultural discrimination to be a legacy of colonialism)9 the artist brings them together and puts them into equal dialogue. Tylor’s work provides a means of continuing culture and redressing the cultural disconnect of colonialisation.

The artists represented in Craftivism. Dissident Objects and Subversive Forms are instigators of imaginative, intelligent and informative discussions about the most pressing environmental issues of our time. There is optimism in the craft of making at a time when the future is uncertain, a will to put the brakes on the ‘great acceleration’ and also to engage in constructive acts of reparation. Furthermore, within the works of these artists lies a poetic yet urgent call to action, so that our children’s children won’t experience nature solely through the glass of the museum display.

8. See Bruce Pascoe, Dark Emu: Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident?, Magabala Books, Broome, WA, 2014.

9. Conversation with James Tylor, July 2018.