Craftivism. Dissident Objects and Subversive Forms—

Anna Briers and Rebecca Coates

8

Craftivism. Dissident Objects and Subversive Forms presents the work of 18 contemporary Australian artists and groups who use craft materials and techniques with a political intent. The artists featured are: Catherine Bell, Karen Black, Penny Byrne, Debris Facility, Erub Arts, Starlie Geikie, Michelle Hamer, Kate Just, Deborah Kelly, Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran, Raquel Ormella, Kate Rohde, Slow Art Collective, Tai Snaith, Hiromi Tango, James Tylor, Jemima Wyman and Paul Yore. Broadening our understanding of craft-making traditions, the artists in this exhibition subvert and extend craft forms as vehicles for activism and social change. Some works encourage social connection between community members and participation in collective processes. Others respond to artistic or political movements. And others yet reveal that the personal remains political, despite the contemporary context being always in flux.

Craftivism – or craft + activism = craftivism – is a term for our times. Coined in the early 2000s by Betsy Greer, a British sociologist, crafter and author of Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism 2013, the term responded to the social trends she was observing unfold at the time, such as yarn bombing, or guerilla knitting, and their viral proliferation across cities around the globe. With a master’s dissertation on knitting, DIY culture and community development, Greer aimed to demonstrate the power of knitting and collaborative craft projects as activist gestures intended to improve the lives of communities and the world at large. These were small actions by everyday people.

Craft, activism and social change have long been interlinked; they have crossed boundaries and borders, genders and generations. William Morris, the great 19th century English textile and wallpaper designer, poet, novelist, translator and social activist, propounded craft as an inherently political medium that could bring about deeper social connection. In reaction to the Industrial Revolution and mass production, Morris and the wider Arts and Crafts movement argued for a return to nature and championed all things handmade.

Craft was not a gendered activity for Morris: he was inspired by guilds and medieval models of production. An active socialist,

Morris argued for makers’ involvement in the entire production process – from design to completion – which, he felt, would combat the alienation created by the division of labour on factory production lines. He believed that good design should be accessible for all to consume. Morris left a profound legacy: for example, he influenced the philosophies and teachings of the great modernist German Bauhaus school of design, architecture and the applied arts, of which weaving was a significant – albeit more often female – part.

Other political movements from the late 19th and early 20th centuries share similar histories of activism and craft. While the visually rich banners of many trade unions were manufactured commercially, the late 19th century women’s suffrage campaigners sported home-made protest banners and parasols exquisitely embroidered in purple, green and white and bearing slogans such as ‘Dare to be Free’ and ‘Alliance and Defiance’.1

In Chile, under the regime of dictator Augusto Pinochet (1973–90), sewing workshops became centres of social resistance for primarily working- class women, who made arpilleras (quilts) from patched-together fabric scraps.4 These textiles often depicted the hardships of everyday life, scenes of government brutality and los desaparecidos (the disappeared people); they were a means by which to memorialise loved ones and to grieve.

1. See Rozsika Parker, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine, Women’s Press, London, 1984, p. 198.

4. Marjorie Agosín, Tapestries of Hope, Threads of Love: The Arpillera Movement in Chile, Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, MD, 2008, p. 73.

Craft, activism and social change have long been interlinked; they have crossed boundaries and borders, genders and generations.

Later in the 20th century, the longstanding Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, established in 1981 to protest against nuclear weapons and active for an amazing 19 years, produced a 9 mile (14.5 km) patchwork rainbow dragon that encircled the base as part of the occupation.2 Words, slogans and peace signs made out of textiles were woven into the chain-link fence to communicate resistance.

Craft endeavours can sometimes have far- reaching political impacts, as two notable quilt projects reveal. The AIDS Memorial Quilt began with a gathering of strangers in June 1987 in a shopfront in San Francisco, USA, with the aim of creating a memorial for those who had died

of AIDS and helping others to understand the devastating impact of the disease.3 Since then, more than 48,000 individual 90 x 180 cm memorial panels have been created, sewn together by friends, lovers and family members. It remains a compelling visual reminder of the AIDS pandemic.

Smuggled across borders, these craft objects documented the repression in Chile and were later used as testimonies in the National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation, which sought to understand the history of political killing and torture under Pinochet. Similar uses of textiles – quilted, cross-stitched or tapestry – can be traced in histories around the globe, including Australia.

Most recently, in an American context, the 2017 Pussyhat moment became an overnight phenomenon when millions of (mostly) women took to the streets, many wearing knitted or crocheted pink hats featuring cat ears, as a response to the misogynistic policies and rhetoric of US President Donald Trump. The Pussyhat Project aimed both to stimulate communities of like-minded knitters, who came together to knit and talk, and to create a politically powerful visual protest.

2. See Maria Elena Buszek (ed.), Extra/ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art, Duke University Press, Durham, NC, 2011, p. 185.

3. The Aids Memorial Quilt, Accessed 12 August 2018, http://www.aidsquilt.org/about/the-aids-memorial-quilt.

Craft making – particularly amongst women – has had a long history as both a means and a symbol of survival and resistance in the face of political persecution and oppression. Suffrage banners, arpilleras and the Pussyhat Project all co-opted craft-based techniques as tools

in the push towards social and political change. Produced by activists, the key function of these objects was to support the act of protest.

It is fair to say that craft is undergoing a renaissance within the contemporary art context. Many leading contemporary artists are increasingly using craft-based techniques and materials in their work. However, the way that they position themselves and their art in relation to clay, textiles and glass, and to activism, protest and change, is radically different from previous decades. The art/craft debate of old is now firmly dead, as contemporary artists extend our understanding of their ideas and concerns through a range of media that includes traditional craft techniques and materials.

These artists and their works are firmly located within the contemporary. Ceramics and textiles are increasingly becoming fixtures of the global contemporary art world: think of Tracey Emin sewing tents to explore personal narratives and Grayson Perry using ceramics and tapestries to rethink the personal as political and offer alternative interpretations of the grand epic narrative tapestry or history painting.

Exhibitions have also promoted the renewed potential of craft materials to extend our understanding of contemporary themes and ideas. Shepparton Art Museum (SAM)’s own acquisitive prize, the Sidney Myer Fund Australian Ceramic Award, continues to showcase works by contemporary artists who rethink the

material and conceptual potential of clay in new and exciting ways. International biennials and triennials, from Venice, Havana, Dakar and São Paulo to the Biennale of Sydney and Brisbane’s Asia Pacific Triennial, have all showcased the work of artists who co-opt and incorporate craft-based techniques and materials. So too have some of the recent major institutional exhibitions in Australia and overseas.

Craftivism. Dissident Objects and Subversive Forms presents the artwork of 18 artists and groups who evidence this moment in contemporary art, embracing ceramics, textiles and fibre art techniques along with everyday materials in order to explore and articulate ideas and issues of our time. A number of themes can be discerned in the artists’ works selected for the exhibition. Gender, representation and identity are ever-present, because ‘the personal as political’ remains relevant today. Many artists are engaged with the land, environmental politics and climate change. Many are concerned about contested borders, immigration and democracy. And many embrace relational production processes that implicitly promote collaboration and social connection. Most of these concerns are not mutually exclusive.

These themes and ideas are considered more extensively in the texts that follow. These include newly commissioned essays by Jessica Bridgfoot, David Cross and Amelia Winata, whom we thank for their insights and ideas, and an essay by SAM’s Senior Curator Anna Briers. This exhibition reveals the myriad ways that artists challenge our perceptions of craft materials and approaches within a contemporary context, inviting us to reflect on social participation and political change.

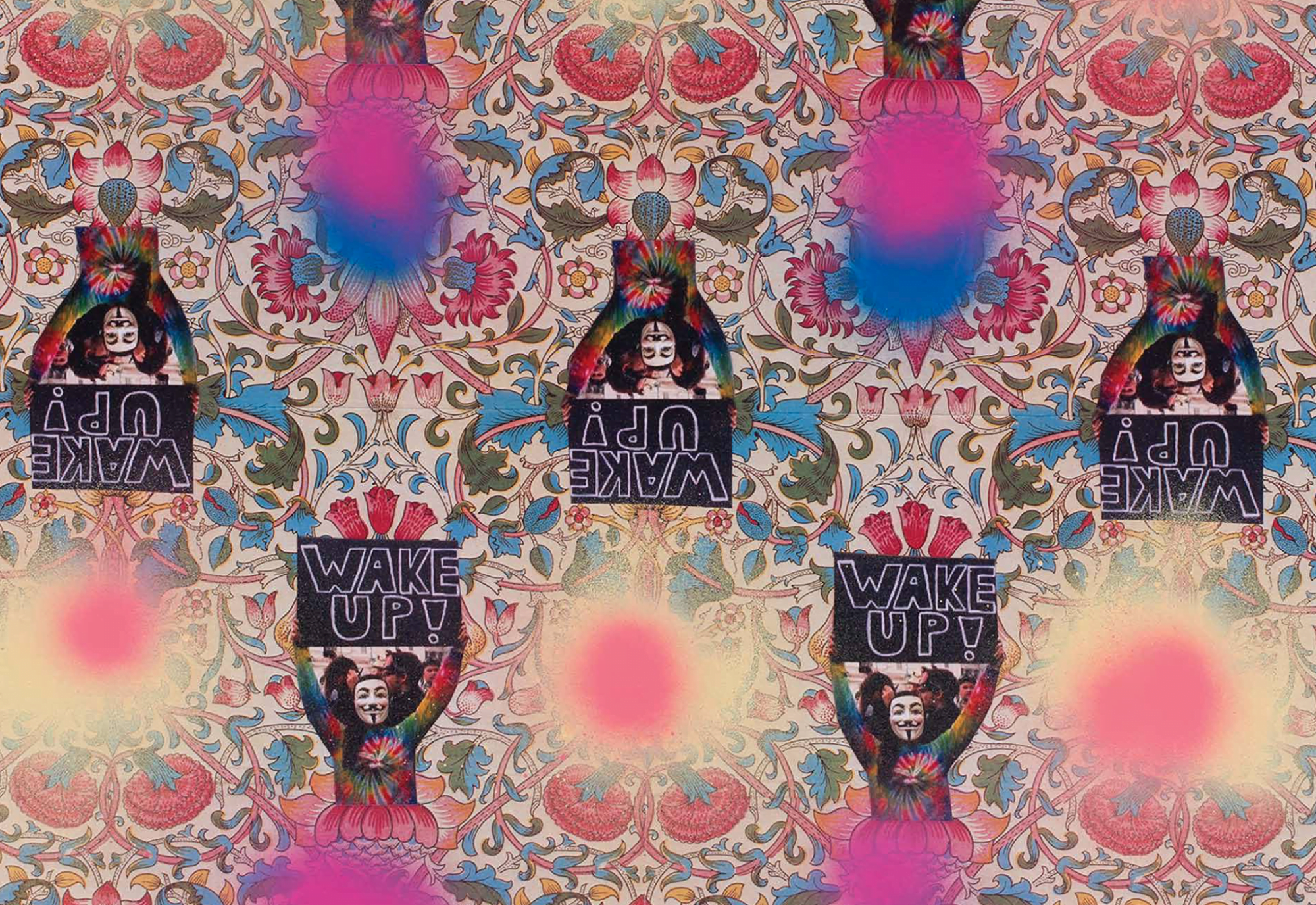

Jemima Wyman. Propaganda textiles – Washington DC, Million Mask March, 5th November 2013 (detail) 2016–17. © the artist, courtesy the artist and Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney / Singapore and Milani Gallery, Brisbane.