Milan Milojevic

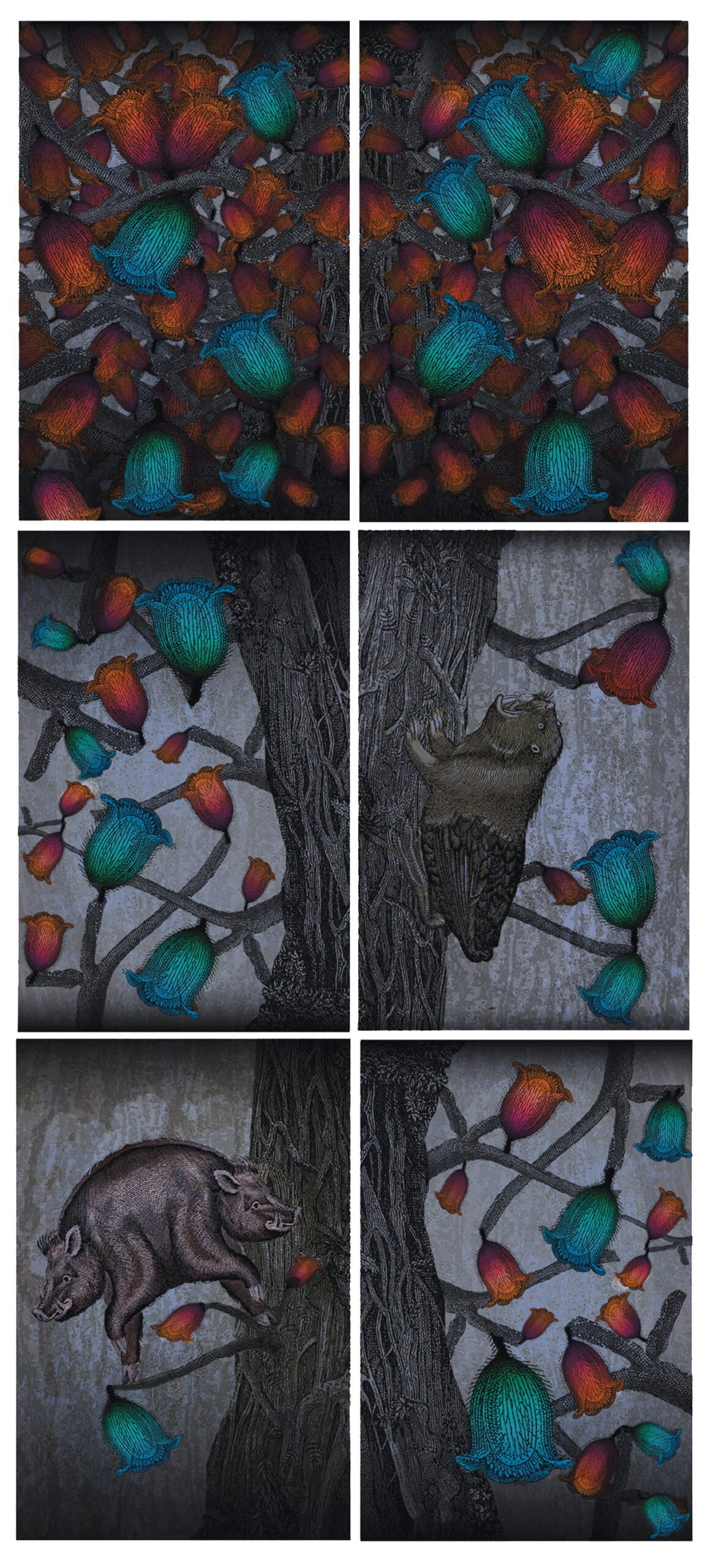

Milan Milojevic was born in Hobart in 1954. His work has been widely exhibited both locally and internationally and is represented in public and private collections. He is the head of the Printmaking Studio at the Tasmanian School of Art, University of Tasmania. Milojevic manipulates the laser printer by hand-mixing pigments and overprinting in multiple layers with traditional mediums to produce digital prints with the richness and luminosity of medieval manuscripts. His imaginary beasts pay homage to the uncharted ‘there be monsters’ regions of early maps. Milojevic’s collaged chimeras and wildernesses serve as a metaphor for constructed identities and cultural knowledge, reflecting his own German and Yugoslavian ancestry. The enchanted forest will present a series of new and existing large-scale digital friezes.

Milan Milojevic in conversation with Melissa Hart

Could you please describe your artistic practice from concept to making?

My practice for the past 20 years has been concerned with addressing issues surrounding cultural identity. The work has evolved through the use of collage sourcing photographs from my family album and images from 17thand 18th century natural history engravings and woodcuts. Traditional and digital printmaking have been pivotal in constructing and resolving these collages.

When and why did you make the decision to work with digital printing?

I started working with digital prints in 1994. My work was primarily photographically based so my interest in the digital process evolved as a natural extension of my practice.

How has this impacted on your practice?

Greatly. The conceptual process is more fluid. It’s much quicker to work through and develop up images and ideas. Digital printmaking has rejuvenated my interest in traditional printmaking and my practice has evolved into a hybrid one, using both traditional and digital elements in the one print. In my case traditional printmaking has impacted greatly on my approach to digital printmaking.

Do you work on your own to produce the prints or do you have assistants?

I work on my own. Initially the imagery is constructed upon the computer and digitally printed, at times built up in layers through the printer. Then it is worked on with traditional media, such as etching and woodcut. The scale of the works can vary, usually the friezes are up to 3.3 metres long but the individual panels are usually 30 x 42 cm in size. The scale of the panel is dictated by the digital printer I use and it also enables the process of layering with traditional media a lot easier, manageable and flexible.

Your works recall the mappa mundi of the Middle Ages, created by early European cartographers to record known and unknown areas of the world. Has living in Tasmania, a place described by early French explorers as ‘The World’s End’, influenced your practice?

My work has been influenced by the great age of exploration and the possibilities of what unknown places might offer and where fact and fiction collide. Tasmania specifically? No.

Did you specifically make Verdure I and Verdure II (both 2007) for The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers? If so, did you have any preconceived ideas or plans for these works? What was your intention?

The ideas for these works were started when I was approached to participate in this exhibition. Initially the concept was to create a large-scale installation, incorporating 5 x 4 metre pieces. I was influenced by 16th and 17th century tapestries, particularly the ones that depicted exotic new worlds incorporating fanciful and fantastic creatures. I wanted to create worlds that totally consumed the viewer, which brought the outside into an interior space in the manner of 18th century French Scenic wallpapers. I never fully developed this idea and the pieces in [The enchanted forest] are just the beginning.

Your works have been framed because The enchanted forest is touring. However, they are not sealed behind perspex. Can you please explain why it was important for you to present the works this way?

Perspex can interfere with the surface quality of the print. I specifically set out to construct the images through layers with subtlety in tone and colour. With the intention of invigorating the image, making it come alive, and Perspex simply deadens that effect. One of the innate qualities of the traditional print is the numerous surfaces the various media can offer and my intention is to retain that quality in my digital prints.

What do you hope the viewer will take away from your work and the exhibition, The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers?

A sense of wonder.

2008Milan Milojevic was born in Hobart in 1954. His work has been widely exhibited both locally and internationally and is represented in public and private collections. He is the head of the Printmaking Studio at the Tasmanian School of Art, University of Tasmania. Milojevic manipulates the laser printer by hand-mixing pigments and overprinting in multiple layers with traditional mediums to produce digital prints with the richness and luminosity of medieval manuscripts. His imaginary beasts pay homage to the uncharted ‘there be monsters’ regions of early maps. Milojevic’s collaged chimeras and wildernesses serve as a metaphor for constructed identities and cultural knowledge, reflecting his own German and Yugoslavian ancestry. The enchanted forest will present a series of new and existing large-scale digital friezes.

Milan Milojevic in conversation with Melissa Hart

Could you please describe your artistic practice from concept to making?

My practice for the past 20 years has been concerned with addressing issues surrounding cultural identity. The work has evolved through the use of collage sourcing photographs from my family album and images from 17thand 18th century natural history engravings and woodcuts. Traditional and digital printmaking have been pivotal in constructing and resolving these collages.

When and why did you make the decision to work with digital printing?

I started working with digital prints in 1994. My work was primarily photographically based so my interest in the digital process evolved as a natural extension of my practice.

How has this impacted on your practice?

Greatly. The conceptual process is more fluid. It’s much quicker to work through and develop up images and ideas. Digital printmaking has rejuvenated my interest in traditional printmaking and my practice has evolved into a hybrid one, using both traditional and digital elements in the one print. In my case traditional printmaking has impacted greatly on my approach to digital printmaking.

Do you work on your own to produce the prints or do you have assistants?

I work on my own. Initially the imagery is constructed upon the computer and digitally printed, at times built up in layers through the printer. Then it is worked on with traditional media, such as etching and woodcut. The scale of the works can vary, usually the friezes are up to 3.3 metres long but the individual panels are usually 30 x 42 cm in size. The scale of the panel is dictated by the digital printer I use and it also enables the process of layering with traditional media a lot easier, manageable and flexible.

Your works recall the mappa mundi of the Middle Ages, created by early European cartographers to record known and unknown areas of the world. Has living in Tasmania, a place described by early French explorers as ‘The World’s End’, influenced your practice?

My work has been influenced by the great age of exploration and the possibilities of what unknown places might offer and where fact and fiction collide. Tasmania specifically? No.

Did you specifically make Verdure I and Verdure II (both 2007) for The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers? If so, did you have any preconceived ideas or plans for these works? What was your intention?

The ideas for these works were started when I was approached to participate in this exhibition. Initially the concept was to create a large-scale installation, incorporating 5 x 4 metre pieces. I was influenced by 16th and 17th century tapestries, particularly the ones that depicted exotic new worlds incorporating fanciful and fantastic creatures. I wanted to create worlds that totally consumed the viewer, which brought the outside into an interior space in the manner of 18th century French Scenic wallpapers. I never fully developed this idea and the pieces in [The enchanted forest] are just the beginning.

Your works have been framed because The enchanted forest is touring. However, they are not sealed behind perspex. Can you please explain why it was important for you to present the works this way?

Perspex can interfere with the surface quality of the print. I specifically set out to construct the images through layers with subtlety in tone and colour. With the intention of invigorating the image, making it come alive, and Perspex simply deadens that effect. One of the innate qualities of the traditional print is the numerous surfaces the various media can offer and my intention is to retain that quality in my digital prints.

What do you hope the viewer will take away from your work and the exhibition, The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers?

A sense of wonder.

2008