Louise Weaver

Louise Weaver was born in Mansfield, Victoria, in 1966. She has an extensive exhibition history in Australia and overseas and her work is represented in major public and private collections around the world.

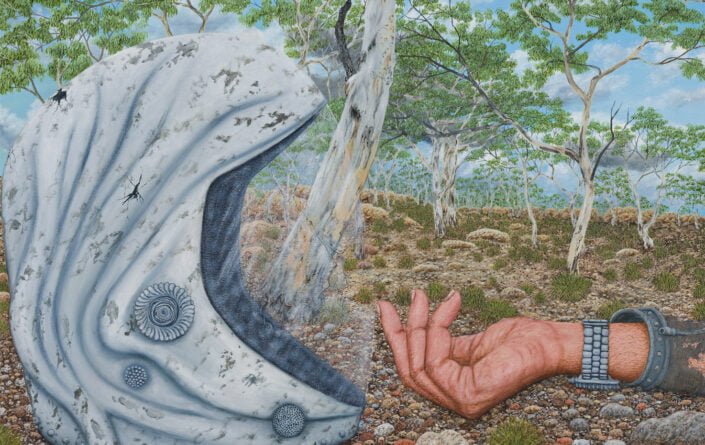

Weaver’s alluring anthropomorphic animals are supremely sophisticated creatures with their crocheted, embroidered and sequined pelts and their mysterious masks. The floor installation presented in The enchanted forest will include new and existing work that evoke folktales of eloquent and charming beasts.

Interview with Louise Weaver

Do you recall wanting to be an artist as a child, and if so what inspired you to pursue art making as a career?

I have always loved resolving ideas through making two and three-dimensional objects. It was apparent to my parents that I was particularly interested in visual art even as a very young child. It was something innate and intuitive that I felt I had to do, and although I studied nursing briefly before studying Fine Art at RMIT – it was in order to have an income that would support my future art career.

In relation to your art practice please make brief mention of your background and training.

I attended RMIT and received a Bachelor of Arts (in painting with distinction) and later a Master of Arts (completed 1996).

Are there artists whose practice and ideas inspire your own work?

There are a number of artists’ works that inspire me. They span many historical and contemporary periods, and are culturally diverse. I am equally inspired by music and literature, personal experience, travel and research.

I enjoy art works created by artists as diverse as Arcimboldo, Hans Holbien, Ito Jakuchu, Indigenous art of Alaska and Siberia, textiles from many historical periods and cultures, and Art Brut/Outsider Art. I have very specified taste ranging from pre-historic artefacts to contemporary works. What unifies my diverse taste is a current of deep personal intensity evident in these works.

Can you make reference to any recurring themes or ideas in your practice?

These obviously vary through one’s career, yet the ideas of the natural world, animals, plants, rocks, minerals, formal aspects of representation and abstraction/design and their intersection in my work. Others include:

- Colour that is divergent from and inclusive of nature.

- Repetition, replication, pattern, chance and spontaneity.

- Concealment and metamorphosis.

- Psychological spaces, and transformation.

There are many themes and ideas one is always growing and refining ideas.

Apart from sculptural installations, since commencing your practice you have made works on paper, paintings, drawings, prints, multiples, ceramics, glass, photographs, digital and sound work. Do you have a preferred medium for exploring the concepts and processes that interest you?

The mediums I use are very diverse yet linked by a philosophy or spirit – basically I will use a medium that best articulates the idea. In most of my work there is a range of media employed.

In the 1990’s you first began exhibiting hard sculptural forms (branches and animals) with a surface of crocheted ‘skin’. One of these works, from 1994, had the literal and self-explanatory title: I am transforming an antler into a piece of coral by crocheting over its entire surface. You are now renowned for your large-scale immersive environments. Can you discuss how your practice has developed since you first made these smaller sculptural forms?

The single sculptural forms such as I am transforming an antler into a piece of coral by crocheting over its entire surface, developed naturally into multiple forms as either collections of forms exhibited together or highly conceptualised ensemble installations that have an interdependence. These are usually large scale and composed of a variety of materials and forms. I still produce small single sculptures; I don’t see a hierarchy between the two. Works evolve naturally, artists like to challenge themselves and utilise new formats, concepts, and complexities, to see if the impossible can be achieved!

Your sculptural environments often incorporate lighting and sound. In what way do you use these elements?

Lighting and sound are intrinsic equal elements to the forms/sculptures. Lighting can reveal and conceal. It can be highly emotive and ‘control’ colour and form in a space. Sometimes tiny lamps are used to create mini environments within an installation. Sound is integral to many of my works; it creates a mood, triggers memory and is temporal. The sound I use is personal; sounds are sometimes sampled from recordings I have listened to throughout my life, adjusted, distorted and reconfigured or may be composed and played by my friends or myself, I make many field recordings of natural sounds, that may relate to the visual component of my work. In relation to your sculptural works, the intricately stitched and embellished surfaces that you create as ‘skin’ (for the found objects, real and taxidermy foam models that you use) both disguise and camouflage the underlying forms. Can you discuss how your interest in covering and simultaneously concealing the surface of these forms developed? The experience of being cocooned in plaster as a child is well documented. The concealing and wrapping of form is evident in my many drawings and paintings from as early as my teenage years, but particularly evident in works from 1986-1990’s, which employ a detailed form of cross-hatching that acts as precursors for some of my sculpture.

I enjoy the idea of replicating or hinting at the natural surface of things through artificial means that play upon and question the appearance of the real. These semi-permeable membranes also allow me to attach a variety of other material to the outer covering. I made a series of minerals, and rocks that trick the eye in the replication of nature. Camouflage is something that interests me. It is a defence and survival mechanism in nature. I am interested in what happens when this protective mechanism is subverted by either changing the environment or the organism. Does a black mink disappear on a black carpet? These ideas are influenced also by my long-standing interest/ knowledge and personal collection of textiles from many cultures and periods including more contemporary Haute Couture etc.

The animals in many of your immersive sculptural environments seem far removed from the wild – and from their real ‘natures’. Can you discuss this in relation to your work Moonlight becomes you*, in The enchanted forest? Together with the act of concealment is there a process of domestication that takes place in your work?

I don’t think there is a process of domestication necessarily just because the animals are removed from the wild. I think this environment is a heightened natural space, islands, glass, water, moonlight, logs and animals. It is real and artificial simultaneously. The environment has changed so the animals have metamorphosed. Even the natural world looks strange, mysterious magical at night. It is a world that transforms from reality into legend and stories that have significant meanings; the animal protagonists in ancient tribal or Shamanistic societies take on magical powers, have human characteristics and act as communicating entities between the spirits and society.

What role do the concepts of revelation and sight play in your work?

I would like to think that a work of art can be a revelatory experience. There is another dimension for communication of ideas other that an obvious one. My work requires contemplation to realise these dimensions.

Would you see a relationship between the hybrid animal forms that you create and issues of environmental sustainability?

Yes, I have produced a variety of work in many media that comment on the environment, and environmental sustainability. I produced work that in part referred to the continuum of the deluge concept, or other natural disasters, change and metamorphosis, of regrowth, revitalisation, evolution that has posed lifeaffirming results. Issues of environmental change and destruction are also evident in my work. Can you discuss the concept of mimicry in relation to your work? I am thinking for instance of when stitches that you employ mimic fur etc. I often utilise materials that replicate or hint at natural surfaces. I have made snowflakes from blown glass, sequins become dew or rain drops, and I enjoy utilising tangible materials to indicate the ephemeral and transitory.

Your work draws our attention to the beauty of everyday objects and natural forms, with colour, ornamentation, texture, detail and design used in your work. Can you discuss your interest in surface and materials?

In am very interested in colour, ornamentation, texture, detail and design. Provided they are integral to the conceptual basis of the work. I occasionally retain the natural colouring of an animal in whole or in part. However I usually transform the animals with saturated exaggerated colour as in the 2003 work, Taking a chance on love.

In the natural world colour and markings act as signs and protective devices, they are forms of ‘signal’. I commandeer these attributes in order to extend their significance in my work.

In my sculpture/ installations these qualities are heightened beyond realism to a point of the extrasensory. Much of my philosophy on this comes from the works of indigenous cultures and historical references, contemporary materials mix with these, Haute couture or super hero costumery, ‘high and low’ art sources. The materials I employ remind one of real surfaces, or patterns of growth and camouflage. I use diamantes as dew, or raindrops emulating the real surface of transitory phenomenon. Often detail in crochet or embellishment such as embroidery lead a viewer to consider a more intimate relationship with the work (as panoramic and microscopic views of the installation).

Elements such as real birds legs emerging from a crocheted covering, causes a shock in the viewer, questioning what is real and fabricated; the two oscillate between themselves and form unexpected associations.

Absurd connections may arise – is a bird balancing a pom-pom on her head or is it part of the plumage? The bob-cat in repose on the carpet island in Moonlight becomes you; has a “lightning” flash as a form of marking that is from Haute Couture yet bobcats have markings also – it is a cross over with animal/human context.

Much of the strange juxtapositions in my work are hinted at in the natural world. For example there are butterflies that have the appearance of owls eyes on their wings. The visual richness of nature is explored and exaggerated in my work.

Your work is incredibly intricate and time consuming – almost obsessive in the way you constrain and cover the surface of forms with an artificial crocheted ’skin’? Is there a psychological space that you occupy when you are making these works?

The working process of crochet is very time consuming, intense and complex. It requires great concentration and mathematical calculation. To negotiate complex forms that are often irregular and asymmetrical, is challenging.

Each new form is a new negotiation of space. I have crocheted over forms and created the ‘shells of forms’. The psychological space is intense; it is not therapeutic or repetitive as I am articulating form and space within a conceptual framework.

The almost obsessive quality you describe as evident in my work, is not a compulsion but a deliberate conceptual strategy. This is consciously created in order to suggest a psychological space.

You conjure a fantastical and wondrous world in your work that can appear removed from the dark and sinister sensibilities that can exist in fairytales and fantasy. This is also a feminised space. Can you comment on this?

If one looks at my entire oeuvre I have always produced work that is deeply personal and evocative in image and in the use of materials. I have always had a sense of fantasy especially in my drawings and paintings: very complex narratives that have continued throughout my career.

I disagree with the assumption that the work lacks the darker or sinister sensibilities that exist in fables or fairytales. The animal works in particular are created by casting the real animal form that has had its skin stripped from its muscles. The inherent violence of this act remains as a latent shadow to my contradictory surface replacement.

There are many other works I have created that can be interpreted as very confronting or perverse and that are often tinged with irony and black humour. I have produced a total body stocking (titled after five) which is constricting and may be seen as having a sinister appearance with two small holes for eyes, which generates a claustrophobic effect.

Branches that grow up from the soles of shoes. A racoon that disguises his tracks by sweeping them away with his tail. Works with human hair, bone and various animal vertebra, teeth and horn. I transform these unsettling elements into magical forms but their power is still present to be exposed to the viewer. The work is feminised in the sense that I often employ techniques and materials usually associated with a gender practice. And I have pioneered some techniques and practices into a fine art/conceptual context.

Were you prone to fantastical imaginings as a child?

I have a vivid imagination; this has not been diminished from childhood.

I am very knowledgeable of fairytales, and am keenly interested in indigenous legends, shamanistic and animistic practices. My work is rich in references and continuums of these legacies which I consider ongoing and relevant to contemporary society.

2008Louise Weaver was born in Mansfield, Victoria, in 1966. She has an extensive exhibition history in Australia and overseas and her work is represented in major public and private collections around the world.

Weaver’s alluring anthropomorphic animals are supremely sophisticated creatures with their crocheted, embroidered and sequined pelts and their mysterious masks. The floor installation presented in The enchanted forest will include new and existing work that evoke folktales of eloquent and charming beasts.

Interview with Louise Weaver

Do you recall wanting to be an artist as a child, and if so what inspired you to pursue art making as a career?

I have always loved resolving ideas through making two and three-dimensional objects. It was apparent to my parents that I was particularly interested in visual art even as a very young child. It was something innate and intuitive that I felt I had to do, and although I studied nursing briefly before studying Fine Art at RMIT – it was in order to have an income that would support my future art career.

In relation to your art practice please make brief mention of your background and training.

I attended RMIT and received a Bachelor of Arts (in painting with distinction) and later a Master of Arts (completed 1996).

Are there artists whose practice and ideas inspire your own work?

There are a number of artists’ works that inspire me. They span many historical and contemporary periods, and are culturally diverse. I am equally inspired by music and literature, personal experience, travel and research.

I enjoy art works created by artists as diverse as Arcimboldo, Hans Holbien, Ito Jakuchu, Indigenous art of Alaska and Siberia, textiles from many historical periods and cultures, and Art Brut/Outsider Art. I have very specified taste ranging from pre-historic artefacts to contemporary works. What unifies my diverse taste is a current of deep personal intensity evident in these works.

Can you make reference to any recurring themes or ideas in your practice?

These obviously vary through one’s career, yet the ideas of the natural world, animals, plants, rocks, minerals, formal aspects of representation and abstraction/design and their intersection in my work. Others include:

- Colour that is divergent from and inclusive of nature.

- Repetition, replication, pattern, chance and spontaneity.

- Concealment and metamorphosis.

- Psychological spaces, and transformation.

There are many themes and ideas one is always growing and refining ideas.

Apart from sculptural installations, since commencing your practice you have made works on paper, paintings, drawings, prints, multiples, ceramics, glass, photographs, digital and sound work. Do you have a preferred medium for exploring the concepts and processes that interest you?

The mediums I use are very diverse yet linked by a philosophy or spirit – basically I will use a medium that best articulates the idea. In most of my work there is a range of media employed.

In the 1990’s you first began exhibiting hard sculptural forms (branches and animals) with a surface of crocheted ‘skin’. One of these works, from 1994, had the literal and self-explanatory title: I am transforming an antler into a piece of coral by crocheting over its entire surface. You are now renowned for your large-scale immersive environments. Can you discuss how your practice has developed since you first made these smaller sculptural forms?

The single sculptural forms such as I am transforming an antler into a piece of coral by crocheting over its entire surface, developed naturally into multiple forms as either collections of forms exhibited together or highly conceptualised ensemble installations that have an interdependence. These are usually large scale and composed of a variety of materials and forms. I still produce small single sculptures; I don’t see a hierarchy between the two. Works evolve naturally, artists like to challenge themselves and utilise new formats, concepts, and complexities, to see if the impossible can be achieved!

Your sculptural environments often incorporate lighting and sound. In what way do you use these elements?

Lighting and sound are intrinsic equal elements to the forms/sculptures. Lighting can reveal and conceal. It can be highly emotive and ‘control’ colour and form in a space. Sometimes tiny lamps are used to create mini environments within an installation. Sound is integral to many of my works; it creates a mood, triggers memory and is temporal. The sound I use is personal; sounds are sometimes sampled from recordings I have listened to throughout my life, adjusted, distorted and reconfigured or may be composed and played by my friends or myself, I make many field recordings of natural sounds, that may relate to the visual component of my work. In relation to your sculptural works, the intricately stitched and embellished surfaces that you create as ‘skin’ (for the found objects, real and taxidermy foam models that you use) both disguise and camouflage the underlying forms. Can you discuss how your interest in covering and simultaneously concealing the surface of these forms developed? The experience of being cocooned in plaster as a child is well documented. The concealing and wrapping of form is evident in my many drawings and paintings from as early as my teenage years, but particularly evident in works from 1986-1990’s, which employ a detailed form of cross-hatching that acts as precursors for some of my sculpture.

I enjoy the idea of replicating or hinting at the natural surface of things through artificial means that play upon and question the appearance of the real. These semi-permeable membranes also allow me to attach a variety of other material to the outer covering. I made a series of minerals, and rocks that trick the eye in the replication of nature. Camouflage is something that interests me. It is a defence and survival mechanism in nature. I am interested in what happens when this protective mechanism is subverted by either changing the environment or the organism. Does a black mink disappear on a black carpet? These ideas are influenced also by my long-standing interest/ knowledge and personal collection of textiles from many cultures and periods including more contemporary Haute Couture etc.

The animals in many of your immersive sculptural environments seem far removed from the wild – and from their real ‘natures’. Can you discuss this in relation to your work Moonlight becomes you*, in The enchanted forest? Together with the act of concealment is there a process of domestication that takes place in your work?

I don’t think there is a process of domestication necessarily just because the animals are removed from the wild. I think this environment is a heightened natural space, islands, glass, water, moonlight, logs and animals. It is real and artificial simultaneously. The environment has changed so the animals have metamorphosed. Even the natural world looks strange, mysterious magical at night. It is a world that transforms from reality into legend and stories that have significant meanings; the animal protagonists in ancient tribal or Shamanistic societies take on magical powers, have human characteristics and act as communicating entities between the spirits and society.

What role do the concepts of revelation and sight play in your work?

I would like to think that a work of art can be a revelatory experience. There is another dimension for communication of ideas other that an obvious one. My work requires contemplation to realise these dimensions.

Would you see a relationship between the hybrid animal forms that you create and issues of environmental sustainability?

Yes, I have produced a variety of work in many media that comment on the environment, and environmental sustainability. I produced work that in part referred to the continuum of the deluge concept, or other natural disasters, change and metamorphosis, of regrowth, revitalisation, evolution that has posed lifeaffirming results. Issues of environmental change and destruction are also evident in my work. Can you discuss the concept of mimicry in relation to your work? I am thinking for instance of when stitches that you employ mimic fur etc. I often utilise materials that replicate or hint at natural surfaces. I have made snowflakes from blown glass, sequins become dew or rain drops, and I enjoy utilising tangible materials to indicate the ephemeral and transitory.

Your work draws our attention to the beauty of everyday objects and natural forms, with colour, ornamentation, texture, detail and design used in your work. Can you discuss your interest in surface and materials?

In am very interested in colour, ornamentation, texture, detail and design. Provided they are integral to the conceptual basis of the work. I occasionally retain the natural colouring of an animal in whole or in part. However I usually transform the animals with saturated exaggerated colour as in the 2003 work, Taking a chance on love.

In the natural world colour and markings act as signs and protective devices, they are forms of ‘signal’. I commandeer these attributes in order to extend their significance in my work.

In my sculpture/ installations these qualities are heightened beyond realism to a point of the extrasensory. Much of my philosophy on this comes from the works of indigenous cultures and historical references, contemporary materials mix with these, Haute couture or super hero costumery, ‘high and low’ art sources. The materials I employ remind one of real surfaces, or patterns of growth and camouflage. I use diamantes as dew, or raindrops emulating the real surface of transitory phenomenon. Often detail in crochet or embellishment such as embroidery lead a viewer to consider a more intimate relationship with the work (as panoramic and microscopic views of the installation).

Elements such as real birds legs emerging from a crocheted covering, causes a shock in the viewer, questioning what is real and fabricated; the two oscillate between themselves and form unexpected associations.

Absurd connections may arise – is a bird balancing a pom-pom on her head or is it part of the plumage? The bob-cat in repose on the carpet island in Moonlight becomes you; has a “lightning” flash as a form of marking that is from Haute Couture yet bobcats have markings also – it is a cross over with animal/human context.

Much of the strange juxtapositions in my work are hinted at in the natural world. For example there are butterflies that have the appearance of owls eyes on their wings. The visual richness of nature is explored and exaggerated in my work.

Your work is incredibly intricate and time consuming – almost obsessive in the way you constrain and cover the surface of forms with an artificial crocheted ’skin’? Is there a psychological space that you occupy when you are making these works?

The working process of crochet is very time consuming, intense and complex. It requires great concentration and mathematical calculation. To negotiate complex forms that are often irregular and asymmetrical, is challenging.

Each new form is a new negotiation of space. I have crocheted over forms and created the ‘shells of forms’. The psychological space is intense; it is not therapeutic or repetitive as I am articulating form and space within a conceptual framework.

The almost obsessive quality you describe as evident in my work, is not a compulsion but a deliberate conceptual strategy. This is consciously created in order to suggest a psychological space.

You conjure a fantastical and wondrous world in your work that can appear removed from the dark and sinister sensibilities that can exist in fairytales and fantasy. This is also a feminised space. Can you comment on this?

If one looks at my entire oeuvre I have always produced work that is deeply personal and evocative in image and in the use of materials. I have always had a sense of fantasy especially in my drawings and paintings: very complex narratives that have continued throughout my career.

I disagree with the assumption that the work lacks the darker or sinister sensibilities that exist in fables or fairytales. The animal works in particular are created by casting the real animal form that has had its skin stripped from its muscles. The inherent violence of this act remains as a latent shadow to my contradictory surface replacement.

There are many other works I have created that can be interpreted as very confronting or perverse and that are often tinged with irony and black humour. I have produced a total body stocking (titled after five) which is constricting and may be seen as having a sinister appearance with two small holes for eyes, which generates a claustrophobic effect.

Branches that grow up from the soles of shoes. A racoon that disguises his tracks by sweeping them away with his tail. Works with human hair, bone and various animal vertebra, teeth and horn. I transform these unsettling elements into magical forms but their power is still present to be exposed to the viewer. The work is feminised in the sense that I often employ techniques and materials usually associated with a gender practice. And I have pioneered some techniques and practices into a fine art/conceptual context.

Were you prone to fantastical imaginings as a child?

I have a vivid imagination; this has not been diminished from childhood.

I am very knowledgeable of fairytales, and am keenly interested in indigenous legends, shamanistic and animistic practices. My work is rich in references and continuums of these legacies which I consider ongoing and relevant to contemporary society.

2008